Tags

Financial Systemic Issues: Booms and Busts - Central Banking and Money - Corporate Governance - Cryptocurrencies - Government and Bureaucracy - Inflation - Long-term Economics - Risk and Uncertainty - Retirement Finance

Financial Markets: Banking - Banking Politics - Housing Finance - Municipal Finance - Sovereign Debt - Student Loans

Categories

Blogs - Books - Op-eds - Letters to the editor - Policy papers and research - Testimony to Congress - Podcasts - Event videos - Media quotes - Poetry

Happy birthday, TARP!

Published by the R Street Institute.

Today, Oct. 3, is the eighth anniversary of congressional passage of the act that created the famous or notorious $700 billion bank bailout program in the midst of financial panic of late 2008. In case you have forgotten, TARP stood for the Troubled Asset Relief Program, and the authorizing legislation was the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008. An emergency it was, with one failure following fast on another.

Eight years on, when we know that the panic passed, when house prices are booming again, when the stock market is high and life has gone on, it’s hard to recreate psychologically the uncertainty and fear of that period. Memories naturally lose their vividness and then fade altogether, making the next cyclical bust more likely.

The design of TARP originally was to quell the crisis by having the U.S. Treasury buy depreciated mortgage-backed securities from banks, removing these “troubled assets” from private balance sheets and thus giving them “relief.” When this was proposed, it was already clear that it was not going to work. The crisis had created insolvencies, with deficit equity capital. By buying assets from banks so they realized big losses, you were not going to fix their capital. Neither would lending them more money from the Federal Reserve fix their capital: if you are broke, no matter how much more you borrow, you are still broke.

By September 2008, the British government already had decided it had to make equity investments in insolvent banks. This replicated the U.S. experience of the 1930s, when the Reconstruction Finance Corp., originally set up to make loans to troubled banks, realized it had to make equity investments instead, in the form of preferred stock. It also replicated the experience of Japan in the 1990s. As TARP was being debated, it seemed to me that the equity investment model was better than the proposed TARP design, and so it proved to be. The RFC overall made a profit on its bank investments, and so, as it turned out, did TARP.

But what Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson had told Congress in getting the legislation passed was that they were approving a program for buying mortgage securities. However, as Paulson revealed in educational crisis memoir “On the Brink,” even as these arguments were being made:

Ben Bernanke had told me that he thought that solving the crisis would demand more than the illiquid asset purchases we had asked for. In his view, we would have to inject equity capital into financial institutions.

Bernanke was right about that, but Paulson thought “we would sabotage our efforts with Congress if we raised our hands midstream and said we might need to inject equity.” Well, you can’t tell the elected representatives of the people what is really going on. When the act did get passed and signed into law Oct. 3, says Paulson: “I made sure to tell…the team: ‘Figure out a way we can put equity in these companies.’” And so they did.

Shortly thereafter, Paulson reflects, “I began seriously to doubt that our asset-buying program could work. This pained me, as I had sincerely promoted the purchases to Congress and the public as the best solution” and “dropping the asset-buying plan would undermine our credibility.” Instead, TARP proceeded by making equity investments in preferred stock.

By now, the TARP investments in banks are almost entirely liquidated at a profit to the Treasury. The program went on to make losing investments in the bailouts of automobile companies (which equally were bailouts of the United Automobile Workers union) and to spend money not authorized by statute on programs for defaulted mortgages. All in all, Oct. 3 launched a most eventful history.

“I had expected [TARP] to be politically unpopular, but the intensity of the backlash astonished me,” wrote Paulson.

Its birthday is a good time to reflect on TARP and try to decide what you would have done in Secretary Paulson’s place, had you been handed that overwhelming responsibility.

The Credit Crunch of 1966: An instructive 50th anniversary

Published in Real Clear Markets.

It’s the 50th anniversary of the Credit Crunch of 1966, which roiled financial markets in August and September of that year. Group financial memory fades, so if you don’t know or remember that there was such a crunch, searing at the time, you are not alone. Yet it taught an essential lesson, again being relearned right now, 50 years later: the Federal Reserve, and central banks in general, simply do not know what the right interest rate is.

Central to the events of 1966 was that the Federal Reserve set the maximum interest rates that banks could pay on their deposits. This was the Fed’s now long-gone but then critical “Regulation Q” authority, at the time considered an essential part of the banking system.

As of July 1966, the Fed had set the interest-rate ceiling on savings deposits at 4 percent. For so-called “multiple maturity” time deposits (where withdrawal was at the depositor’s notice) it was 4 percent for a minimum maturity of up to 89 days, and 5 percent for 90 days or more. For fixed-maturity date time deposits, the ceiling was 5.5 percent. In September 1966, it dropped to 5 percent, except that deposits of more than $100,000 (that’s $743,000 in 2016 dollars) could still get 5.5 percent.

How did the Fed know those numbers were right? It didn’t, as events demonstrated. Most of the time over the preceding decades, they had set the ceiling over market rates, so it generally hadn’t been an issue.

But in 1966, there was strong credit demand from an extended economic expansion, plus inflationary pressure from the Vietnam War and “Great Society” deficits. Interest rates in the open market went much higher than before. Three-month Treasury bill yields got to 5.59 percent, the federal funds rate to 5.77 percent and commercial paper rates to 6 percent. Market rates on negotiable CDs went over the ceilings. “The prime rate briefly reached the then unheard of level of 6 percent,” wrote economist Albert Wojnilower. A 6 percent prime rate was the highest it had been in more than 30 years.

This time, the Fed refused to raise the ceiling in line with the market, in part reflecting political pressure to limit competition for deposits in order to favor savings-and-loan institutions, which were stuck with long-term mortgages at low fixed rates. Lending long and borrowing short was already dangerous in 1966.

Naturally, in response, people took their money out of both banks and savings and loans and put it into higher-yielding conservative investments, a perfectly sensible thing to do. This process had a cumbersome name at the time: “disintermediation”—a problem created entirely by regulation. Unable to expand their funding, the banks cut back on their loans. The savings and loans cut way back on their mortgage loans. “For most people, residential mortgage money was unobtainable…there was a sharp slump in mortgage loans and housing starts,” wrote The New York Times.

Banks also cut back on their previously expanding investments, notably in municipal bonds. Both banks and thrifts worried about their ability to fund their existing balance sheets. As described by the theoretician of financial crises, Hyman Minsky: “By the end of August, the disorganization in the municipals market, rumors about the solvency and liquidity of savings institutions, and the frantic [funding] efforts by money-center banks generated what can be characterized as a controlled panic.” Not allowed to bid competitive rates for deposits, as the St. Louis Fed’s history of the credit crunch reports: “Banks had never before experienced a large outflow of time deposits.”

So the Fed fixed prices and the result was the credit crunch. Following Wojnilower’s lively account: “Lending to all but the most established and necessitous customers was halted abruptly. Chief executives of leading banks reportedly were humbled to the point of pleading with their counterparts in industry to renew their CDs.” Further, in order to the raise needed funds, there was “the apparent inevitability of massive distress sales of long-term assets into a paralyzed marketplace.”

Who came to the rescue? The cause of the problem. “The gravity of the situation penetrated to an initially incredulous Federal Reserve,” Wojnilower continues. Banks were invited to borrow at the discount window in the face of “the very lively fears that major banks might have to close their doors.”

The shock of the credit crunch led the Fed into “a long-lasting series of private and public reassurances that no such crisis would ever be permitted to recur.” How did that work out? Three years later came the more severe credit crunch of 1969. As economist Charlotte E. Ruebling wrote at the time, “market interest rates have soared to levels never before reached in this country,” but “rates on deposits at banks and other financial institutions have been held much lower.” By the Fed, of course.

The authors of Regulation Q had a really bad idea, based on the false assumption that the Fed would somehow know the right answer. But the Fed did not know what the right interest rate was in 1966, or 1969—nor do they know it now. They never have and cannot know it. Put not your faith in their dubious “expertise.”

Negative rates aren’t working. Why do central banks persist?

Published in Real Clear Markets with Paul Kupiec.

Monetary policies in Europe and Japan have produced trillions of dollars of bonds with negative nominal interest rates in the hope of stimulating economic growth. Indeed, the Bank of Japan’s recent policy announcement doubles-down on this strategy by pledging to cap 10-year Japanese government bond yields at zero until the central bank hits its 2 percent inflation target.

But there is little evidence that negative interest rates are stimulating economic growth. Economic data suggest that consumers are actually saving more in countries with negative interest rates. And business investment, far from being stimulated by near-zero borrowing costs, is weak across the board. It’s time for a critical reassessment of unconventional post-crisis monetary policy experiments.

A typical consumer’s lifecycle has three phases – a borrowing phase, a saving phase and a phase for consuming savings in retirement. The aging of developed countries has increased the economic importance of the latter two lifecycle phases. While negative real interest rates benefit borrowing households, they are a tax on savers and those in retirement.

With negative nominal interest rates, prudently sock away your income for years and you are certain to receive less money than you invested. On top of that, monetary authorities worldwide target perpetual inflation, so chances are that you will face a higher price level in the future. Faced with this double whammy, economists predict that consumers should spend rather than save, but the data strongly suggest that households are compensating for negative interest rates by saving more, not less.

Recent OECD data show that, as average short-term interest rates turned negative, household savings rates increased in Switzerland, Germany, Sweden, Denmark and Japan. The OECD forecasts decade-high household savings rates in 2016 for all these countries except Japan.

Recent negative and near-zero interest rate policies have also had unanticipated impacts on business investment. If businesses followed economic textbooks, they would invest in activities that are profitable when expected revenues and costs are discounted using their average cost of funds. Under this decision rule, investment should increase when monetary policies force interest rates to zero or below, because more investments are profitable when a business’ cost of borrowing falls.

But many business mangers apparently skipped this economics lecture. Research has shown that many firms evaluate investments by discounting future cash flows using a management-set hurdle rate, not their firm’s cost of raising new funds. Survey evidence finds that firms set investment hurdle rates between 12 to 15 percent for investments similar to their existing business lines, and significantly higher for new business ventures.

Moreover, the evidence from multiple countries suggests that business hurdle rates are “sticky” over time. Firms do not appear to adjust their hurdle rates in response to changes in short-term interest rates. For example, a recent Federal Reserve Board study concludes that business investment hurdle rates have changed little since the 1980s, despite nearly double-digit declines in corporate borrowing costs.

The missing piece in the business investment puzzle is uncertainty. When businesses perceive high downside risks, they wait to invest. The delay allows firms to acquire new information and avoid potential downside losses by postponing investing until the data confirm an improved outlook. This behavior mimics the Federal Reserve and other monetary authorities’ habit of delaying action until additional data confirm the underlying economic trend.

The option to wait has the potential to put a huge drag on business investment. When monetary authorities use highly publicized, radical approaches like QE and negative interest rates and justify the policies as “insurance” against a deflationary spiral, they are themselves creating uncertainty. The more monetary authorities push the negative interest rate frontier to save their economies from disaster, the bigger the uncertainty they telegraph to businesses and consumers about downside risks.

Against mounting evidence, it is becoming harder to cling to the theory that near-zero and negative interest rates stimulate economic growth. When rates are negative, savers appear to save more, not less; retirees consume less to conserve their nest eggs; and business investment stagnates, as the value of the option to wait for an improved economic outlook grows.

But near-zero and negative interest rates do have one beneficiary – governments. Near zero and negative nominal rates reduce budget deficits because governments borrow virtually for free or even get paid to issue debt. So although near-zero and negative interest rates cloud the outlook for economic growth, these monetary policies have provided a silver lining for treasuries and finance ministries.

Taking on Leviathan

Published in the Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679), the great philosopher of the authoritarian state, in a famous metaphor portrayed the government as a dominating giant or Leviathan, animated by absolute sovereignty, and passing out rewards and punishments as it saw fit. It alone could control the unruly passions of the people and create stability and safety.

Today’s “administrative state”—or government bureaucracy, acting simultaneously as sovereign legislator, executive, and judge—brings Hobbes’ image of the giant vividly to mind.Nowhere is his metaphor more apt than in the government’s attempts at “systemic financial stability.” Hobbes’ 21st century acolytes include former Senator Chris Dodd (D-Conn.) and former Congressman Barney Frank (D-Mass.), whose Dodd-Frank Act sought to prevent financial crises, as Hobbes sought to prevent civil wars, by enlarging the giant. Now, as then, how to control the unruly passions, lust for power, and misguided enthusiasms of the state itself is left unanswered.

However, Congressman Jeb Hensarling (R-Tex.), who chairs the House Financial Services Committee, is now taking on Leviathan in the financial system with the proposed Creating Hope and Opportunity for Investors, Consumers and Entrepreneurs (CHOICE) Act. If it seems unlikely that he could fell the giant altogether, perhaps he could limit and better control and confine it, at least with respect to banking and the people’s money. If he succeeded, the federal government would place more emphasis on competitive markets and less on the diktats of the central bank and regulatory bureaucrats whom Dodd-Frank made sovereign.

Writing his book Leviathan in 1651, in the wake of the English Civil War and the beheading of King Charles I, Hobbes had this to say: “By art is created that great LEVIATHAN called a COMMONWEALTH or STATE (in Latin, CIVITAS), which is but an artificial man, though of much greater stature and strength.”

He went on:

sovereignty is an artificial soul, as giving life and motion to the whole body; the magistrates and other officers of judicature and execution, artificial joints; reward and punishment (by which fastened to the seat of the sovereignty, every joint and member is moved to perform his duty) are the nerves.

Moreover,

Salus Populi (the people’s safety) its business; counsellors, by whom all things needful to know are suggested unto it, are the memory; equity and laws, an artificial reason and will; concord, health; sedition, sickness; and civil war, death.

Writing four decades before the founding of the Bank of England, Hobbes can be forgiven for not mentioning the central bank, which has since become a key element of sovereignty. We need to extend his metaphor to include it. We could say that the central bank is a kind of artificial heart pumping the circulating blood of credit and money, making sure to lend the government as much as it wants. It often pumps this blood of credit to an excessive extent, causing financial markets to inflate, be overly sanguine, then bust, constrict their flows and suffer the heart attacks of financial panics.

Three centuries or so after Hobbes, Leviathan developed a new capability: that of constructing vast shell games guaranteeing huge quantities of other people’s debt and taking vast financial risks, while pretending that it wasn’t doing this, and keeping this debt off the books. I refer to the invention of government-sponsored enterprises like Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, and to related schemes such as government-sponsored insurance companies, like the Federal Savings and Loan Insurance Corporation and the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation. All serve as Leviathan’s artificial stomach and gluttonous appetite for risk, causing in time obesity, flatulence, indigestion, and finally the heartburn of publicly admitted insolvency.

Although financial panics temporarily render Leviathan stunned and confused, in short order it resumes its energetic activity and ambitious pursuit of greater power. Writing legislation in 2010, in the wake of the financial crisis of 2007 to 2009, Senator Dodd and Representative Frank ordered Leviathan to make deep expansions into the financial sector. The people’s financial safety and concord became defined as a new supreme demand for “compliance” with the orders of government bureaucrats, who were assumed to know the right answers.

The Dodd-Frank Act was passed in 2010 on party line votes at a time of insuperable Democratic majorities in both houses of Congress. Shortly after voting it in, the Democrats suffered stinging losses in that year’s congressional elections. No subsequent Congress would ever have dreamed of passing anything remotely resembling Dodd-Frank, but financial Leviathan had already been put on steroids and unleashed.

Now comes Chairman Hensarling to try to bring financial Leviathan back under control. The CHOICE Act would reform Leviathan’s activity in a wide swath of financial areas. It would:

Remove onerous Dodd-Frank burdens on banks that maintain a high tangible capital ratio (defined as 10 percent of total assets), thus creating a simple rule instead of the notoriously complex ones now in force.

Force the Financial Stability Oversight Council into greater transparency by cutting back the power of this committee of regulators to make opaque decisions in secret.

Correct the egregiously undemocratic governance of another bureaucratic invention, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, by giving it a bipartisan board and subjecting it to the congressional oversight and appropriations process that every federal agency should have.

Require greater accountability and transparency from Leviathan’s heart, the Federal Reserve.

Require cost-benefit analysis for new regulations and a subsequent measurement of whether they achieved their goals—imagine that!

Repeal the “Chevron Doctrine” that leads judges to defer to federal agencies. This is essential, as bureaucrats make ever-bolder excursions beyond their legal authority.

Take numerous steps to relieve Leviathan’s heavy hand on small businesses and small banks.

The CHOICE Act will likely be taken up by the House Financial Services Committee this fall—and be ready for further consideration if, as is forecast by most people, Republicans retain control of the House of Representatives in the upcoming election. The debates about the bill will be contentious and sharply partisan, with vehement opposition from those who love Leviathan. How far the reform bill can go depends on how other parts of the election turn out.

Will financial Leviathan grow ever fatter, more arrogant, and more intrusive? Or can it be put on a long-term diet by constraining its arrogance, correcting its pretensions, imbuing its artificial soul with behavior befitting a republic, and put in the service of a limited government of checks and balances?

The CHOICE Act is a good start at this daunting and essential project.

The new century brings remarkable downshift in per-capita GDP growth

Published in Real Clear Markets.

For the half-century from 1950 to 2000, U.S. real gross domestic product per capita grew at an average rate of 2.22 percent per year. For the first 15 years of the 21st century so far, this key measure of the overall standard of living has grown, on average, at only 0.89 percent.

Of course, a growth rate per person of 0.89 percent is still growth, and growth in output per person sustained over years is still a notable achievement of the market economy.

But the difference between growth rates of something over 2 percent and a little less than 1 percent is a very big deal. How much difference does that drop make, if it continues? Thanks to the always-surprising power of compound growth rates over time, the difference in the resulting long-term standard of living is huge.

In a lifetime of 80 years, for example, per capita GDP growth of 0.89 percent per year will double the economic standard of living-on average, people will become twice as well off as before. But with a growth rate of 2.22 percent, GDP per capita will more than quintuple in the same 80 years-people will be five times as well off. Such amazing improvement has actually happened historically beginning with the economic revolutions of the 19th century and continuing through the 20th. In 1950, U.S. real per capita GDP was $14,886 (using constant 2009 dollars). By 2000, it was $44, 721-thus 3X in 50 years.

The downshift of our new century is apparent when we look at the average growth rates in successive 15-year periods, as shown in the table.

Why the downshift and will it continue? The answer, as with so many things in economics, is that we do not know.

One theory now proposed is “secular stagnation.” This is not really so much a theory as giving a different name to slower growth rates. “Stagnation” was also a noted economic assertion in the 1940s– just before the postwar boom and on the verge of 50 years of solid growth. The great economist, Joseph Schumpeter, writing in 1949 on “modern stagnationism,” observed that “stagnationist moods had been voiced, at intervals, by many economists before.” Now they are being voiced again. They were always wrong before. Will they be right this time?

Among the factors we may speculate contribute to the markedly slower growth in real per capita GDP of this century are: the drag from financial crises and their resource misallocations; the aging of the population, with lower birth rates and long retirements; the fall in labor participation rates, so there are fewer producers as a percent of the population; the ever-more oppressive tangle of government regulations, so that “compliance” with the orders issued by bureaucrats becomes the top priority; and the massive monetary distortions of central banks, pretending to know what they are doing.

Can all this continue to suppress the underlying growth dynamic of scientific advance, innovation, entrepreneurship and enterprise of a market economy? Unless the government interventions get a lot worse (which they may!), I believe the current stagnationists will likely join their historical predecessors among the ranks of the false prophets. Let us hope so.

Economic reform for Puerto Rico

Published by the R Street Institute.

The attached letter was submitted to the Bipartisan Congressional Task Force on Economic Growth in Puerto Rico.

Among the most fundamental of Puerto Rico’s many economic problems is that it is “stuck in a monetary union with the United States” (as Desmond Lachman of the American Enterprise Institute has correctly characterized it). In this situation of being forced to use the U.S. dollar, the Puerto Rican economy is simply uncompetitive, but the use of exchange rate policies to improve competitiveness or cushion budget tightening’s impact on domestic demand is precluded.

This is the same massive problem that Greece had and still has from being stuck in the monetary union of the euro. With any external currency adjustment forbidden, all the adjustment falls on internal reduction of costs. As Greece demonstrates, this continues to be very difficult and daunting, both economically and politically. This is true even after its creditors have taken huge haircuts. Puerto Rico’s creditors will take big haircuts, too, but that won’t solve its ongoing lack of competitiveness or the impact of the required budget tightening.

The European Union leadership feared that Greece’s exit from the euro might set off the unraveling of their whole common currency project. In contrast, there is not the slightest possibility that whatever happens in Puerto Rico will affect the stability or dominant role of the U.S. dollar. Even in the Greek case, European policy makers did seriously consider a back-up plan for a paper currency to be issued by Greek banks which would certainly have depreciated against the euro.

Dr. Lachman argues that Puerto Rico “needs the boldest of economic programs.” My suggestion is that the Task Force should consider “thinking about the unthinkable,” and include in its work a study of the “outside the box” possibility of currency reform for Puerto Rico. This would involve creating a new Puerto Rican currency which would be considerably devalued with respect to the U.S. dollar, thus allowing external, not only wrenching internal, adjustment of Puerto Rico’s uncompetitive cost structures. There is plenty of precedent for such currency reform, although this case is certainly complicated by the status of Puerto Rico as a territory. Could a U.S. territory have its own currency? Why not?

In such a study, one would have to consider the balance sheets of all the Puerto Rican depositories and how they would be affected in detail by denomination in a new currency, how various contracts would be affected, how exchange between the new currency and other currencies would be introduced, whether a new Puerto Rican central bank would be established, and many other problems of transition and functioning, of course. Existing Puerto Rican government debt in U.S. dollars would not be subject to redenomination, but this debt, a growing amount of it in default, is going to have to be significantly written down in any case.

Does the current monetary union pose deep problems for Puerto Rico? Undoubtedly. Would it make sense to release Puerto Rico from being stuck in a monetary union in which it cannot compete? Possibly. Would this be better than the Greek model of forcing internal cost deflation while providing big external subsidies? Probably. It does seem sensible to take a serious look at the possibility of currency reform.

Thank you for the chance to comment on this critical issue. It would be a pleasure to provide any further information which might be helpful.

Japan versus the United States in per-capita GDP

Published by the R Street Institute.

We often see and hear in the media about the “stagnation” of economic growth in Japan. Let’s look at the numbers and see how Japan has done compared to the United States in the 15 years of the 21st century so far.

If we measure by growth in real gross domestic product (GDP), without considering changes in population, Japan’s economic growth is far behind that of the United States. From 2000 to 2015, its real GDP grew an average of 0.72 percent per year, while U.S. real GDP grew an average of 1.77 percent.

In average growth rates, more than 1 percent per year is a big difference, indeed, as it compounds over time. Over 15 years, this annual growth rate difference would add up to U.S. GDP being 30 percent larger, compared to 11 percent larger for Japan, a difference of 19 percentage points.

However, economic well-being is not measured by aggregate GDP, but by GDP per capita. The question is how much production there is per person. In this case, measuring per-capita growth gives us a very different outcome.

In 2015, Japan’s population was essentially the same as it was in 2000, with an average annual growth rate of 0.01 percent. The corresponding annual growth rate of the U.S. population was 0.87 percent. So the U.S. added 39 million more people over the period to provide for.

Thus real GDP growth per capita in Japan was 0.71 percent per year. In the United States, it was 0.89 percent – a much more similar number. The growth rate advantage over Japan, measured per capita, is reduced to a modest 0.18 percent.

If 0.71 percent growth is “stagnant,” what is 0.89 percent?

Iron Chancellor was a good actuary too

Published in the Financial Times.

Sir, “Retirement age for young Germans will have to rise to 69, central bank warns” (Aug. 16). That is a quite reasonable, even generous, retirement age if you are going to live to 85 or 90 or more.

Moreover, it would not be the highest retirement age Germany has had. When Otto von Bismarck introduced the first state pension scheme in the German Empire of 1889, the retirement age was set at 70! Needless to say, on average you were going to live many fewer years after 70 then than now. The Iron Chancellor knew what he was doing, actuarially speaking

When is the next financial crisis due?

Published by the R Street Institute.

House prices, commercial real estate prices, stock prices and bond prices are all very high. Remarkable asset-price inflations have been induced by the low, zero or negative interest-rates manipulations of central banks – needless to say, including the Federal Reserve. The U.S. Office of Financial Research recently warned of the systemic financial risks which accompany such low interest rates and elevated asset prices.

A century and a half ago, the great banking theorist Walter Bagehot quoted the saying that “John Bull can stand many things, but he cannot stand 2 percent.” When interest rates went as low as 2 percent, investors began to do foolish things which inevitably ended badly.

If 2 percent is a dire situation, how about 0 percent?

Will there be another financial crisis? Of course there will. But when? However much we speculate and however endless the talk about it, nobody knows. For although we can, by science, know with certainty and utter precision when and where the total solar eclipse will appear a year from now, no such science applies to the financial future.

Nonetheless, we can consider the long-term historical average, which is for financial crises to appear about every 10 years. As former Fed Chairman Paul Volcker so wittily said: “About every 10 years we have the biggest crisis in 50 years.” A decade is, it seems, long enough for human beings to forget the supposedly unforgettable lessons of the last crisis.

The last crisis peaked with the panic of 2008. Add 10 years to that, and you get the next crisis in 2018. That seems like a reasonable guess.

‘Commercial’ bank is misnomer. ‘Real estate’ bank is more apt

Published in American Banker.

Comparing banking in the 1950s to today, we find giant changes that surely would have astonished the bankers of that earlier time. What’s the biggest and most important one?

You might nominate the shrinkage in the total number of U.S. banks from over 13,200 in 1955 to only about 5,300 now — a 60 percent reduction. Or you might say the rise of interstate banking, or digital technology going from zero to ubiquitous, or the growth of financial derivatives into hundreds of trillions of dollars, or even air conditioning making banking facilities a lot more pleasant.

You might point out that the whole banking industry’s total assets were only $209 billion in 1955, less than one-tenth the assets of today’s JPMorgan Chase, compared with $15 trillion now. Or that total banking system equity was $15 billion, less than 1 percent of the $1.7 trillion it is now. Of course, there have been six decades of inflation and economic growth. The nominal gross domestic product of the United States was $426 billion in 1955, compared with $17.9 trillion in 2015. So banking assets were 49 percent of GDP in 1955, compared with 83 percent of GDP now.

But I propose that the biggest banking change during the last 60 years is none of these. It is instead the dramatic shift to real estate finance and thus real estate risk, as the dominant factor in the balance sheet of the entire banking system. It is the evolution of the banking system from being principally business banks to being principally real estate banks.

In 1955, commercial and industrial loans were 40 percent of total banking loans and real estate loans only 25 percent. The great banking transition set in after 1984. The share of C&I loans kept falling, down to about 20 percent of total loans, while real estate loans rose to about 50 percent, with a bubble-induced peak of 60 percent in 2009. In this remarkable long-term shift, the share of real estate loans doubled, while the share of commercial and industrial loans dropped in half. The lines crossed in 1987, three decades ago and never met again, despite the real estate lending busts of the early 1990s and of 2007-9.

The long-term transition to concentration in real estate would have greatly surprised the authors of the original National Banking Act of 1864, which prohibited national banks from making any real estate loans at all. This was loosened slightly 1913 by the Federal Reserve Act and significantly in 1927 by the McFadden Act — in time for the ill-fated real estate boom of the late 1920s.

The real estate concentration is even more pronounced for smaller banks. For the 4,700 banks with assets of less than $1 billion, real estate loans are 75 percent of all loans, about the same as their bubble-era peak of 76 percent.

Moreover, in another dramatic change from the 1950s, the securities portfolio of the banking system has also become heavily concentrated in real estate risk. Real estate securities reached 74 percent of total banking system securities at the height of the housing bubble. They have since moderated, to 60 percent, but that is still high.

In terms of both their lending and securities portfolios, we find that commercial banks have become basically real estate banks.

Needless to say, this matters a lot for understanding the riskiness of the banking system. The assets underlying real estate loans and securities are by definition illiquid. The prices of these assets are volatile and subject to enthusiastic run-ups and panicked, unexpected drops. When highly leveraged on bank balance sheets, real estate over banking’s long history has been the most reliable and recurring source of busts and panics.

A good example is the frequency of commercial bank failures in 2007-12 relative to their increasing ratio of real estate loans to total loans at the outset of the crisis in December 2007. From the first quartile, in which real estate loans are less than 57 percent of loans, to the third quartile, in which they are over 72 percent, the frequency of failure triples, and failures are nine times as great for the highest ratio quartile as for the lowest. In the fourth quartile, real estate loans exceeded 83 percent of loans, and the failure rate is over 13 percent, which represents 60 percent of all the failures in the aftermath of the bubble. The 50 percent of banks with the highest real estate loan ratios accounted for 82 percent of the failures.

Central to the riskiness of leveraged real estate is the risk of real estate prices falling rapidly from high levels — and right now those prices are again very high. The Comptroller of the Currency’s current “Risk Perspective” cites rapid growth in commercial real estate loans, “accompanied by weaker underwriting standards” and “concentration risk.”

The predominance of real estate finance in banking’s aggregate banking balance sheet makes that risk far more important to the stability of the banking system than the bankers of the 1950s could ever have imagined.

OFR points to low interest rates without mentioning the Fed

Published by the R Street Institute.

In the July 2016 edition of its Financial Stability Monitor, the U.S. Treasury Department’s Office of Financial Research (OFR) points out multiple times that exceptionally low interest rates are exacerbating systemic risks. But OFR somehow never mentions the Federal Reserve as the cause the low interest rates and, therefore, the risks.

The OFR was set up to analyze and report on systemic financial risk. Governments and central banks are among the most important causes of this risk. But can one part of the government ever say that another part is generating systemic risk, even when it manifestly is? Apparently not.

Thus, we discover in the OFR report that:

U.S. interest rates have declined to ultra-low level levels, which can motivate excessive risk-taking and borrowing.

Note the passive voice: “have declined.” The relevant actor, the Fed, is not cited.

Key market risks stem from persistently low U.S. interest rates.

And who is setting these rates?

The report points to the “situation exacerbated by the U.K. vote.” So we can mention Brexit, but not the Fed.

Low U.S. long-term interest rates underpin excesses in investor risk-taking, as well as high U.S. equity prices and commercial real estate prices…these excesses…could compound other threats, including credit risk.

Somehow no mention of the Fed’s strategy to create “wealth effects” by promoting investor risk-taking.

Low interest rates have prompted investors to take risks to get better returns.

Who did the prompting?

Commercial real estate prices climbed rapidly…generally attributed to low interest rates and low vacancy rates. However, such large and rapid price increases can make an asset market more susceptible to large price declines.

Yup, the danger of central banks promoting wealth effects.

Is the OFR able to say what it really thinks? If not, it needs to be replaced as soon as possible by somebody who can.

Who will pay for the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corp.’s huge losses?

Published in Real Clear Markets.

The government’s pension insurance company, the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation (PBGC), is broke. Because its creditors can’t demand their money immediately, it won’t have spent

its last dollar for “a significant number of years” yet (maybe ten) — but its liabilities of $164 billion are nearly twice its assets of $88 billion: there is no way it can honor all its obligations.

The PBGC has two programs, one insures single employer pensions and the other multiemployer, union-sponsored pensions. Both are insolvent, but the multiemployer program is in far worse shape: it is well and truly broke. Its liabilities of $54 billion are 27 times its assets of $2 billion. There are on top of that “reasonably possible” losses of another $20 billion.

The PBGC was supposed to be, according to its charter act, financially self-supporting: obviously it isn’t. Also according to the act, its liabilities are not obligations of the United States government: but it couldn’t continue to exist even for a minute except as part of the government. Will the taxpayers end up paying for its losses-or if not, who?

A month ago (June 17, 2016), Labor SecretaryThomas Perez, who chairs the PBGC board, wrote disingenuously to the Congress, that the board wants to work with Congress “to ensure the continued solvency of the multiemployer program.” A forthright statement would have been: “to address the disastrous insolvency of the multiemployer program.”

In the background of the PBGC’s huge net worth deficit are a large number of deeply underfunded multiemployer pension funds. “Overall,” Perez’s letter admitted, “plan assets in the multiemployer pension system are now less than half of earned benefits.” You could call that underfunding with a vengeance.

An instructive example is the Central States plan (formally, the Teamsters union’s Central States, Southeast and Southwest Areas Pension Fund). The financial stress of this large and utterly insolvent multiemployer plan brings the inescapable problems into sharp focus. As an officially “critical and declining” multiemployer pension plan, Central States was able under the Kline-Miller Multiemployer Pension Reform Act of 2014, to submit a plan, which ran to 8,000 pages, to reduce its pension obligations to a level more in line with its assets and income. The reduced pensions under this proposal, consistent with the 2014 act, would still have been higher than if the fund went into the PBGC.

The U.S. Treasury Department rejected the proposed plan, pointing out various technical shortcomings and the hard fact that even with the pension reductions, the proposal did not fix Central States’ long-term insolvency-which is indeed a requirement included in the 2014 act (put in, apparently, at the insistence of the Democratic legislators). This has the ironic result, as the Washington Post editorialized, that “if Central States collapses and the PBGC takes over, retirees would, by law, get even less than they would under the just-rejected proposal.” And that is assuming that the PBGC itself can pay its obligations over time, which it can’t.

Some observers have suggested that the Treasury’s motivation was political rather than technical. In other words, that the incumbent administration could not afford to approve any reduction, even if a better deal than the PBGC would provide, in the pension benefits of a union-sponsored pension plan, no matter how broke that plan is.

Of course, the Treasury’s action leaves Central States just as broke as it was before, the multiemployer pension system just as hopelessly underfunded as it was before, the PBGC’s multiemployer program just as broke as it was before, and the overall PBGC the same.

Let’s consider the fundamental truths. The money needed to pay the pension obligations of Central States was simply not put into the pension fund, so it’s not there to pay them. The money needed to pay the pension obligations of the multiemployer pension system as a whole was simply not put into the funds, so it’s not there to pay them. The insurance premiums needed to make the PBGC able to honor its insurance obligations were not set at the necessary levels and were therefore not collected, so it is not there to pay them.

The resulting deficits are huge and real. Someone is consequently going to suffer the losses which are unavoidable because they have already happened. Who is that someone?

There are multiple candidates for taking or sharing in the losses:

1. The pension beneficiaries who have claims on insolvent pension plans. Their pensions could be reduced, as in the Detroit bankruptcy, or if they are still working, their own contributions to the pension plans significantly increased, or both. Also, they might start paying individual insurance premiums to the PBGC, just as government-insured mortgage borrowers pay individual premiums to the Federal Housing Administration.

2. The employers who unwisely committed to pension plans whose benefits have proved unpayable. They could make much bigger contributions to funding the plans, or pay vastly higher insurance premiums to the PBGC, or both.

3. The union sponsors of the multiemployer plans. They could be removed from any control of insolvent multiemployer plans, in effect putting such plans into PBGC receivership, as in a normal insolvency proceeding and as with failed single employer pension plans. There is no reason for multiemployer plans to be different. But as it is now, the PBGC merely pays the tab for failed multiemployer plans.

4. The creditors of employers. The deficit of a pension plan is an unsecured creditor’s claim on the employer. That could be made a senior claim, just as deposits were made senior claims on banks after the financial crisis of the 1980s. This would force some of the burden on to other creditors of failed employers.

5. Taxpayers. It is inevitable that a taxpayer bailout will be proposed, despite the pious statutory assurance that PBGC’s debts are not government obligations. Against this proposal, it will be fairly asked why people with no pensions themselves or who don’t have defined benefit pensions should pay for those who do have them-a good question. On the other side, the hardship of existing pensioners of insolvent pension funds will be sincerely urged.

6. Some combination of the above.

Needless to say, whoever ultimately has to take the unavoidable losses will not like it.

Consider this striking historical parallel to the probable fate of the PBGC’s multiemployer program: the decade-long descent into humiliating failure of the government’s deposit insurer, the Federal Savings and Loan Insurance Corporation (FSLIC). This government insurer, along with the savings and loan industry whose obligations it guaranteed, sank into a sea of insolvency in the 1980s. When this finally had to be publicly confessed, FSLIC became notorious. It certainly seems that the PBGC is the new FSLIC.

Negative real interest rates are politics

Published by the R Street Institute.

In a recent Wall Street Journal piece, Jason Zweig cites Harvard’s Carmen Reinhart as rightly pointing out that “low interest rates will keep transferring massive amounts of wealth from savers to borrowers.” In fact, short-term interest rates are not merely “low,” but in real, inflation-adjusted terms, they are negative.

The negative real interest rates imposed by the Federal Reserve for more than seven years now have, indeed, expropriated savings and subsidized borrowings. In particular, they have subsidized leveraged speculation, providing essentially free margin loans to the speculators at the expense of the savers. As a temporary crisis measure in a financial panic, one can defend this. But not for more than seven years.

A cynical description of politics is taking money from the public and giving it to your friends. In simple fact, when you use the power of the government to take money from some people and give it to others, that is absolutely politics, no matter what else it might also be called. For example, it might also be called “monetary policy.” By imposing negative real interest rates, the Fed is without question engaging in political decisions and political actions.

The average real yield on six-month Treasury bills since the end of 2008 has been negative 1.3 percent. The 50-year historical average is about positive 1.6 percent. The difference goes right out of the pockets of the savers and into the pockets of borrowers. Of course, the biggest borrower of all, which gets by far the biggest transfer of money, is the federal government itself. In this sense, negative interest rates are another way of imposing a tax. Imposing a tax is obviously a political act.

Where does the Fed get the legitimacy to impose taxes and to take some people’s money and give it to others, for years after the crisis has ended? How and to whom is it accountable for these political acts?

Where, how and to whom, indeed?

Housing Finance: Two strikes, and now?

Published in the Urban Institute.

Memories fade. So while trying to draw conclusions about going forward, we should also do our best to remember our past expensive lessons in politicized housing finance.

It should be most sobering to Americans engaged in mortgage lending that the U.S. housing-finance sector collapsed twice in three decades—a pretty dismal record. There was first the collapse of the savings and loan-based system in the 1980s, then again that of the Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac-based system in the 2000s. The first also caused the failure of the government’s Federal Savings and Loan Insurance Corp.; the second forced the government to admit that the U.S. Treasury really was on the hook for the massive debt of Fannie and Freddie, frequent protestations to the contrary notwithstanding. The first generated a taxpayer bailout of $150 billion; the second, a taxpayer bailout of $187 billion. That’s two strikes. Are we naturally incompetent at housing finance?

In both cases, the principal housing-finance actors had tight political ties to the government, which allowed them to run up risk while claiming a sacred housing mission. The old U.S. League for Savings, the trade association for savings and loans, was in its day a serious political force and closely linked with the Federal Home Loan Bank Board. In their glory days, in turn, Fannie and Freddie bestrode the Washington and housing worlds like a hyper-leveraged colossus. In retrospect, these were warning signs.

The savings and loans did what the regulators told them to do: make long-term, fixed-rate mortgage loans financed short. Fannie and Freddie were viewed as a solution to this interest-rate-risk problem, then had a credit-risk disaster instead. They, too, did what the regulators told them to do: acquire a lot of lower-credit-quality loans. Thinking that regulators know what risks will come home to roost in the future is another warning sign.

We need to eschew all politicized schemes and move to something more like a real housing-finance market, if we want to avoid strike three.

Pollock testifies on CHOICE Act before House Financial Services

Published by the R Street Institute.

R Street Distinguished Senior Fellow Alex J. Pollock testified July 12, 2016 before the House Financial Services Committee about the CHOICE Act, legislation that proposes to loosen regulatory controls on banks that choose to hold sufficient capital to offset their risk to the financial system. Video of Alex’s testimony, as well as Q&A about the Volcker Rules and other reforms to the Dodd-Frank Act, is embedded below.

Seven steps to housing-finance reform

Published by the R Street Institute.

The attached policy brief appeared in the Housing Finance Reform Incubator report published in July 2016 by the Urban Institute.

The giant American housing finance sector is as important politically as it is financially, which makes it hard to reform. From the 1980s on, it was unique in the world for its overreliance on the “government-sponsored enterprises” (GSEs), Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac—privately owned, but privileged and with “implicit” government guarantees. According to Fannie and Freddie, their lobbyists and members of Congress reading scripts from Fannie in its former days of power and glory, this made American housing finance “the envy of the world.”

In fact, it didn’t, and the rest of the world did not experience such envy. But Fannie and Freddie did attract investment from the rest of the world, which correctly saw them as U.S. government credit with a higher yield: this channeled the savings of thrifty Chinese and others into helping inflate American house prices into their historic bubble. Fannie and Freddie were a highly concentrated point of systemic vulnerability.

Needless to say, Fannie and Freddie, and American housing finance in general, then became “the scandal of the world” as they went broke. What schadenfreude my German housing-finance colleagues enjoyed after years of being lectured by the GSEs on the superiority of the American system. Official bodies in the rest of the world pressured the U.S. Treasury to protect their investments in the insolvent Fannie and Freddie, which of course it did and does. The Treasury is also protecting the Federal Reserve, which in the meantime became the world’s biggest investor in Fannie and Freddie securities.

More than seven years later, America is still unique in the world for centering its housing-finance sector on Fannie and Freddie, even though they have equity capital that rounds to zero. Now they are primarily government-owned and entirely government-controlled housing-finance operations, completely dependent on the taxpayers. Nobody likes this situation, but it has already outlasted numerous reform proposals.

Is there a way out that looks more like a market and less like a statist scheme? A way that reduces the distortions of excessive credit that inflates house prices, runs up leverage and sets up both borrowers and lenders for failure? In other words, can we reduce of the chance of repeating the mistakes of 1980 to 2006? I suggest seven steps to reform American housing finance:

Turn Fannie and Freddie into SIFIs at the “10 percent moment”

Enforce the law on Fannie and Freddie’s guarantee fees

Encourage skin in the game from mortgage originators

Form a new joint FHLB mortgage subsidiary

Create countercyclical LTVs

Reconsider local mutual self-help mortgage lenders

Liquidate the Fed’s MBS portfolio

Turn Fannie and Freddie into SIFIs at the ’10 percent moment’

The original bailout deal for Fannie and Freddie created a senior preferred stock with a 10 percent dividend. As everybody knows, the amended deal makes all their net profit a dividend, which means there will never be any reduction of the principal, no matter how much cash Fannie and Freddie send the Treasury. It is easy, however, to calculate the cash-on-cash internal rate of return (IRR) to the Treasury on its $189.5 billion of senior preferred stock. So far, this is about 7 percent – positive, but short of the required 10 percent. But as Fannie and Freddie keep sending cash to the Treasury, the IRR will rise and will reach a point when total cash paid is equivalent to a 10 percent compound return, plus repayment of the entire principal. That is what I call the “10 percent moment.” It provides a uniquely logical point for reform, and it is not far off, perhaps late 2017 or early 2018.

At the 10 percent moment, whenever it arrives, Congress should declare the senior preferred stock fully repaid and retired, as in financial substance it will have been. Simultaneously, Congress should formally designate Fannie and Freddie as Systemically Important Financial Institutions (SIFIs). That they are indeed SIFIs – able to put not only the entire financial system but also the finances of the U.S. government at risk – is beyond the slightest doubt.

As soon as Fannie and Freddie are officially, as well as in economic fact, SIFIs, they will get the same minimum capital requirement as bank SIFIs: 5 percent of total assets. At their current size, this would require about $250 billion in equity. This is a long trip from zero, but they could start building capital, while of course being regulated as undercapitalized until they aren’t. Among other things, this means no dividends on any class of stock until the capital requirement is met.

As SIFIs, Fannie and Freddie will get the Fed as their systemic risk regulator. In general, they should be treated just like big bank SIFIs. Just as national banks have the Fed, as well as the Comptroller of the Currency, they will have the Fed, as well as the Federal Housing Finance Agency.

Since it is impossible to take away Fannie and Freddie’s too-big-to-fail status, they should pay the government for its ongoing credit guaranty, just as banks pay for theirs. I recommend a fee of 0.15 percent of total liabilities per year.

Fannie and Freddie will be able to compete in mortgage finance on a level basis with other SIFIs, and swim or sink according to their competence.

Enforce the law on Fannie and Freddie’s guarantee fees

In the Temporary Payroll Tax Cut Continuation Act of 2011, Title IV, Section 401, “Guarantee Fees,” Congress has already decided how Fannie and Freddie’s guarantee fees (g-fees) must be set. Remarkably, the law is not being obeyed by their conservator, the Federal Housing Finance Agency.

The text of the statute says the guarantee fees must “appropriately reflect the risk of loss, as well the cost of capital allocated to similar assets held by other fully private regulated financial institutions.”

This is unambiguous. The simple instruction is that Fannie and Freddie’s g-fees must be set to reflect the capital that private banks would have to hold against the same risk, and also the return private banks would have to earn on that capital. The economic logic is clear: to get private capital into the secondary mortgage market, make Fannie and Freddie price to where private financial institutions can fairly compete.

This is, in fact, a “private sector adjustment factor,” just as the Fed must use for its priced services. The difference is that the Fed obeys the law and the FHFA doesn’t.

Of course, the FHFA finds this legislative instruction highly inconvenient politically, so ignores it or dances around it. But Congress didn’t write the act to ask the FHFA what it liked, but to tell it what to do. The FHFA needs to do it.

Encourage skin in the game for mortgage originators

A universally agreed-upon lesson from the American housing bubble was the need for more “skin in the game” of credit risk by those involved in mortgage securitization. But lost in most of the discussion was the optimal point at which to apply credit-risk skin in the game. This point is the originator of the mortgage loan, which should have a junior credit risk position for the life of the loan. The entity making the original mortgage is in the best position to know the most about the borrower and the credit risk of the borrower. It is the most important point at which to align incentives for creating sound credits.

The Mortgage Partnership Finance (MPF) program of the Federal Home Loan Banks was and is based on this principle. (I had the pleasure of leading the creation of this program.) The result was excellent credit performance of the MPF mortgage loans, including through the crisis. The principle is so obvious, isn’t it?

I do not suggest making this a requirement for all originators, but to design rules and structures in mortgage finance to encourage this optimal credit strategy.

Form a new joint FHLB mortgage subsidiary

Freddie Mac was originally a wholly owned, joint subsidiary of the 12 Federal Home Loan Banks (FHLBs). Things might have turned out better if it had remained that way.

FHLBs (there are now 11 of them) are admirably placed to operate secondary markets with the thousands of smaller banks, thrifts and credit unions—and perhaps others—that originate mortgages in their local markets. As lenders to these institutions, FHLBs know and have strong ability to enforce the obligations of the originators, both as credit enhancers and as servicers. But to be competitive, and for geographic diversification, they need a nationwide scope.

The precedent for the FHLBs to form a nationally operating mortgage subsidiary is plain. They should do it again.

Create countercyclical LTVs

As the famous investor Benjamin Graham pointed out long ago, price and value are not the same: “Price is what you pay, and value is what you get.”

Likewise, in mortgage finance, the price of the house being financed is not the same as its value, and in bubbles, prices greatly exceed the sustainable value of the house. Whenever house prices are in a boom, the ratio of the loan to the sound lendable value becomes something much bigger than the ratio of the loan to the inflated current price.

As the price of any asset, including houses, goes rapidly higher and further over its trend line, the riskiness of the future price behavior becomes greater—the probability that the price will fall a lot keeps increasing. Just when lenders and borrowers are feeling more confident because of high collateral “values” (really, prices), their danger is, in fact, growing. Just when they are most tempted to lend and borrow more against the price of the asset, they should be lending and borrowing less.

A countercyclical LTV (loan-to-value ratio) regime would reduce the maximum loan size relative to current prices, in order to keep the maximum ratio of loan size to underlying lendable value more stable. The boom would thus induce smaller LTPs (loan-to-price ratios); steadier LTVs; and greater down payments in bubbly markets—thus providing an automatic dampening of price inflation and a financial stabilizer.

Often discussed are countercyclical capital requirements for financial institutions, which reduce the leverage of those lending against riskier prices. The same logic applies to reducing the leverage of those who are borrowing against risky prices. We should do both.

Canada provides an interesting example of where countercyclical LTVs have actually been used.

Reconsider local mutual self-help mortgage lenders

In the long-forgotten history of mortgage lending, an important source of mortgage loans were small, mutual associations owned by their depositors and operating with an ethic that stressed saving, self-discipline, self-help, mutual support and homeownership. Demonstrated savings behavior and character were key qualifications for borrowing. The idea of a mortgage was to pay it off.

In the Chicago of 1933, for example, the names of such associations included: Amerikan, Archer Avenue, Copernicus, First Croatian, Good Shepherd, Jugoslav, Kalifornie, Kosciuszko, Narodi, Novy Krok, Polonia, St. Paul, St. Wenceslaus, Slovak and Zlata Hora…you get the idea.

In my opinion, the ideals of these mutual associations are worth remembering and reconsidering; they might be encouraged (not required) again. We would have to make sure that current loads of regulatory compliance costs are not allowed to smother any such efforts at birth.

Liquidate the Fed’s MBS portfolio

What is the Fed, a central bank, doing holding $1.7 trillion of mortgage-backed securities (MBS)? The founders of the Fed and generations of Fed officers since would have found that impossible to imagine. The MBS portfolio exists because the Fed was actively engaged in pushing up house prices, as part of its general scheme to create “wealth effects,” by allocating credit to the housing sector using its own balance sheet. It succeeded— house prices have not only risen rapidly, but are back over their trend line on a national average basis.

Why is the Fed still holding all these mortgages? For one thing, it doesn’t want to recognize losses when selling its vastly outsized position would drive the market against it. Some economists argue that even big losses do not matter if you are a fiat currency central bank. Perhaps not, but they would be embarrassing and unseemly.

Whatever justification there may have been in the wake of the collapsed housing bubble, the Fed should now get out of the business of manipulating the mortgage market. It can avoid recognizing any losses by simply letting its mortgage portfolio steadily run off to zero over time through maturities and prepayments. It should do so, and cease acting as the world’s biggest savings and loan.

Especially with the reforms to Fannie and Freddie discussed above, we would get closer to having a market price of mortgage credit. Imagine that!

Envoi

Will these seven steps solve all the problems of American mortgage finance and ensure that we will never have another crisis? Of course not. But they will set us on a more promising road than sitting unhappily where we are at present.

Testimony to House Financial Services Committee on the CHOICE Act

Published by the R Street Institute.

Mr. Chairman, Ranking Member Waters and members of the committee, thank you for the opportunity to be here today. I am Alex Pollock, a senior fellow at the R Street Institute, and these are my personal views. I spent 35 years in banking, including 12 years as president and CEO of the Federal Home Loan Bank of Chicago and then 11 years as a fellow of the American Enterprise Institute, before joining R Street earlier this year. I have both experienced and studied many financial cycles, including the political contributions and reactions to them, and my work includes the issues of banking systems, central banking, risk and uncertainty in finance, housing finance and government-sponsored enterprises and the study of financial history.

“Detailed intrusive regulation is doomed to fail.” This is the considered and, in my view, correct conclusion of a prominent expert in bank regulation, Sir Howard Davies, former chairman of the U.K. Financial Services Authority and former director of the London School of Economics. Detailed, intrusive regulation is what we’ve got, and under the Dodd-Frank Act, ever more of it. “Financial markets cannot be directly ‘controlled’ by public authorities except at unsustainable cost,” Davies adds. Surely there is a better way to proceed than promoting unfettered bureaucratic agencies trying through onerous regulation to do something at which they are doomed to fail.

I believe the CHOICE Act offers the opportunity of a better way, precisely by offering banks a fundamental choice.

The lack of sufficient capital in banks is a permanent and irresistible temptation to governments to pursue intrusive microregulation, which becomes micromanagement. This has an underlying logic to it. In a world in which governments explicitly and implicitly guarantee bank creditors, the government in effect is supplying risk capital to the banks which do not have enough of their own. Suppose the real requirement in a true market would be for an equity capital ratio of 8 percent of assets, but the bank has only 4 percent. The government implicitly provides the other 4 percent – or half the required capital. We should not be surprised when the, in effect, 50 percent shareholder demands a significant say about how the bank is run, even if the resulting detailed regulations will not be successful.

However, the greater the equity capital is, the less rationale there is for the detailed regulation. In our example, if the bank’s own capital were 8 percent, the government’s effective equity stake would be down to zero. This suggests a fundamental and sensible trade-off: more capital, reduced intrusive regulation. But want to run with less capital? You get the intrusive regulation.

In other words, the CHOICE Act says to U.S. banks: “You don’t like the endless additional regulation imposed on you by the bloated Dodd-Frank Act. Well, get your equity capital up high enough and you can purge yourself of a lot of the regulatory burden, deadweight cost and bureaucrats’ power grabs which were all called forth by Dodd-Frank.”

CHOICE does not set up higher capital as a mandate or an order to increase the bank’s capital. Rather it offers a very logical decision to make between two options. These are:

Option One: Put enough of your equity investors’ own money in between your creditors and the risk that other people will have to bail the creditors out if you make mistakes. Mistakes are inevitable when dealing with the future, by bankers, regulators, central bankers and everybody else. The defense is equity capital; have enough so that the government cannot claim you are living on the taxpayers’ credit, and therefore cannot justify its inherent urge to micromanage.

Option Two: Don’t get your equity capital up high enough and instead live with the luxuriant regulation of Dodd-Frank. This regulation is the imposed cost of, in effect, using the taxpayers’ capital instead of your own to support your risks.

I believe the choice thus offered in the proposed act is a truly good idea. To my surprise, The Washington Post editorial board agrees. They write:

More promising, and more creative, is Mr. Hensarling’s plan to offer relief from some of Dodd-Frank’s more onerous oversight provisions to banks that hold at least 10 percent capital as a buffer against losses…such a [capital] cushion can offer as much—or more—protection against financial instability as intrusive regulations do, and do so more simply.

Very true and very well-stated.

Making the choice, banks would have to consider their cost of capital versus the explicit costs and opportunity costs of the regulatory burden. Some might conclude that Option Two would yield higher returns on equity than Option One; some will conclude that Option One is the road to success. I imagine some banks would choose one option, while some would choose the other.

Different choices would create a healthy diversification in the banking sector. They would also create, over time, a highly useful learning experience for both bankers and governments. One group would prove to be sounder and to make greater contributions to economic growth and innovation. One group would, in time, prosper more than the other. The other group will end up less sound and less successful. Which would be which? I think the group with more capital, operating in relatively freer markets with greater market discipline, would prove more successful. But we would find out. Future think-tank fellows could write highly instructive papers on the contrast.

Of course, to establish the proposed choice, we have to answer the question: how much capital makes is high enough? For a bank to make the deal proposed in the CHOICE Act, it would have to have a tangible leverage capital ratio of at least 10 percent. That is a lot more than current requirements, but is it enough?

Consider the matter first in principle: without doubt there is some level of equity capital at which this trade-off makes sense—some level of capital at which everyone, even habitual lovers of bureaucracy, would agree that the Dodd-Frank burdens become superfluous or, at least, cause costs far in excess of their benefits.

What capital ratio is exactly right can be, and is, disputed. Because government guarantees, subsidies, mandates and interventions are so intertwined with today’s banks, there is simply no market answer available. Moreover, we are not looking for a capital level which would remove all regulation—only the notorious overreaction and overreach of Dodd-Frank. For example, the CHOICE Act requires to qualify for Option One that, in addition to 10 percent tangible capital, a bank must have one of the best two CAMELS ratings by the regulator—”CAMELS” being assessments of capital, asset quality, management, earnings, liquidity and sensitivity to market risk.

Numerous proposals for the right capital levels have been made. However, the fact that no one knows the exact answer should not stop us from moving in the right direction.

Among various theories and studies, the International Monetary Fund concluded that “bank [risk-based] capital in the 15-23 percent range would have avoided creditor losses in the vast majority of past banking crises,” and that this range is consistent with “9.5 percent of total leverage exposure.” Obviously, a 10 percent level is somewhat more conservative than that.

Economist William Cline recently concluded that “the optimal ratio for tangible common equity is about 6.6 percent of total assets and a conservative estimate…is about 7.9 percent.”

Paul Krugman proposed a maximum assets-to-capital ratio of 15:1, which is equivalent to a leverage capital ratio of 6.7 percent. Anat Admati and Martin Hellwig came in much higher, arguing for a leverage capital requirement of 20 percent to 30 percent – however, with no empirical analysis. Economists David Miles, Jing Yang and Gilberto Marcheggiano estimated optimal bank capital at about 20 percent of risk-weighted assets, which in their view means a 7 percent to 10 percent leverage capital ratio.

In a letter to the Financial Times, a group of academics asserted a requirement for 15 percent leverage capital, but a study by economists Anil Kashyap, Samuel Hanson and Jeremy Stein proposed risk-based capital of 12 percent to 15 percent, which means a leverage capital ratio of 6 percent to 8 percent. Banking expert Charles Calomiris proposed 10 percent leverage capital.

All in all, it seems to me that the 10 percent tangible leverage capital proposed in the CHOICE Act to qualify for Option One is a fair level. It subtracts all intangible assets and deferred-tax assets from the numerator of the ratio, and adds the balance sheet equivalents of off-balance sheet items to the total assets in the denominator. Thus, it is a conservatively structured measure.

In 2012, Robert Jenkins, then a member of the Bank of England’s Financial Policy Committee, gave a speech to the Worshipful Company of Actuaries entitled “Let’s Make a Deal,” which put forward the same fundamental idea as does the CHOICE Act. The proposed deal was a “rollback of the rule book” in exchange for banks raising “their tangible equity capital to 20 percent of assets.” He explained the logic as follows:

“We all agree that too many bankers got it wrong.”

“We acknowledge that too many regulators got it wrong.”

So, the best solution is to increase the tangible equity and “in return we can pare back the rule book—drastically.”

Under the CHOICE Act, in exchange for 10 percent tangible leverage capital, along with a high CAMELS rating, the deal is, to repeat, not to eliminate all regulation, but to exit from the excesses of Dodd-Frank. We should view Dodd-Frank in its historical context, as an expected political overreaction to the then-recent crisis. Now, for banks taking Option One, there would still be plenty of regulation, but not the notoriously onerous entanglements of Dodd-Frank. In exchange for Jenkins’ suggested move to 20 percent leverage capital, one would rationally eliminate a lot more regulation and bureaucratic power—to pare it back, as he says, “drastically.” The proposed act is more moderate.

The CHOICE Act uses the simple and direct measure of tangible leverage capital. This is, in my judgment, superior to the complex and sometimes opaque measures of risk-adjusted assets and risk-based capital. Although, in theory, risk-based capital might have been attractive, in fact, its manifestations have been inadequate, to say the least. Risk adjustments assume a knowledge in regulatory bureaucracies about what is more or less risky that does not exist—because risk is in the future. They are subject to manipulations and mistakes and, more importantly, to political factors. Thus, for example, Greek sovereign debt was given a zero risk weighting and ended up paying lenders 25 cents on the dollar. The risk weightings of subprime MBS are notorious. Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac debt and preferred stock were given preferential risk weightings, which helped inflate the housing bubble—a heavily political decision and a blunder.

The deepest problem with risk weightings is that they are bureaucratic, while risk is dynamic and changing. Designating an asset as low risk is likely to induce flows of increased credit, which end up making it high risk. What was once a good idea becomes a “crowded trade.” What was once a tail risk becomes instead a highly probable unhappy outcome.

Of course, no single measure tells us all the answers. Of course, managing a bank or supervising a bank entails understanding multiple interacting factors. But for purposes of setting up the choice for banks in the proposed act, I believe the simplicity of tangible leverage capital is the right answer.

In my judgment, the proposed choice between Option One and Option Two makes perfect sense. It takes us in the right direction and ought to be enacted.

Thank you again for the chance to share these views.

Mismatch has led us into trouble many times before

Published in the Financial Times.

Financial events cycle and financial ideas cycle. Here the United Kingdom is again, with real estate generating financial stress. As Patrick Jenkins rightly points out (“Open-ended property funds are accidents waiting to happen,” July 6), this vividly displays “the fundamental mismatch between a highly illiquid asset class and a promise of instant access to your money.”

This same mismatch has led us into trouble many times before. It is why the original U.S. National Banking Act of 1864 prohibited the national banks, as issuers of deposits and currency payable on demand, from making any real estate loans at all. “The property market is already too volatile,” says Mr. Jenkins. Yes, and it always has been.

In tracking homeownership, marriage matters

Published in Real Clear Policy with Jay Brinkmann.

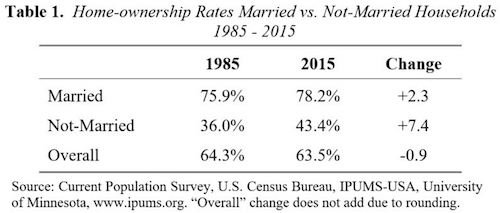

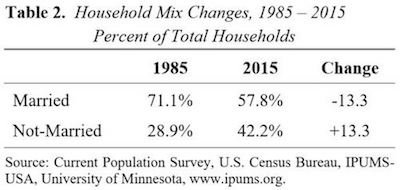

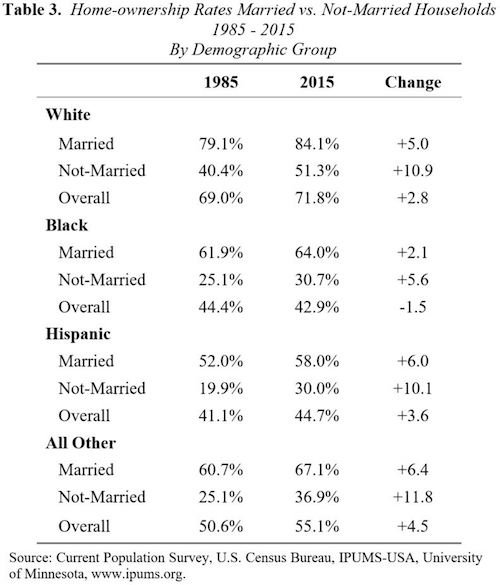

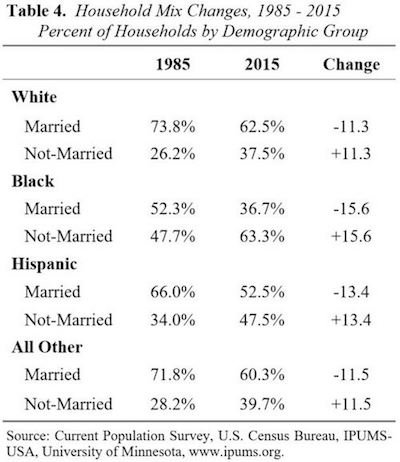

Homeownership long has been considered a key metric for economic well-being in the United States. Thus, many are dismayed by the fact that, at 63.5 percent, the 2015 overall homeownership rate appears to be lower than the 64.3 percent of 1985, a generation ago. But viewed in another, arguably more relevant way, the underlying trend shows the homeownership rate is, in fact, increasing, not decreasing.

How so? Key to the trend is the extremely strong relationship between marriage and homeownership — a relationship seldom, if ever, addressed in housing-finance discussions. But if you think about it, it’s obvious that homeownership should be higher among married couples than among other households; in fact, it’s remarkably higher.