Tags

Financial Systemic Issues: Booms and Busts - Central Banking and Money - Corporate Governance - Cryptocurrencies - Government and Bureaucracy - Inflation - Long-term Economics - Risk and Uncertainty - Retirement Finance

Financial Markets: Banking - Banking Politics - Housing Finance - Municipal Finance - Sovereign Debt - Student Loans

Categories

Blogs - Books - Op-eds - Letters to the editor - Policy papers and research - Testimony to Congress - Podcasts - Event videos - Media quotes - Poetry

What is the actual collateral for a mortgage loan?

Published in Real Clear Markets.

“Economics and finance are like going to the dog races,” my friend Desmond Lachman of the American Enterprise Institute is fond of saying. “Stand in the same place and the dogs will come around again.” So they will.

U.S. financial markets produced sequential bubbles – first in tech stocks in the 1990s and then in houses in the 2000s.

“What is the collateral for a home mortgage loan?” I like to ask audiences of mortgage lenders. Of course, they say, “the house,” so I am pleased to tell them that is the wrong answer. The correct answer is the price of the house. My next question is, “How much can a price change?” Ponder that. The correct answer is that prices, having no independent, objective existence, can change a lot more than you think. They can go up a lot more than you think probable, and they can go down a lot more than you think possible. And they can do first one and then the other.

This is notably displayed by the asset price behavior in both the tech stock and housing bubbles. As the dogs raced around again, they made a remarkably symmetrical round trip in prices.

Graph 1 shows the symmetrical round trip of the notorious “irrational exuberance” in dot-com equities, followed by unexuberance. It displays the NASDAQ stock index expressed in constant dollars.

Now consider houses. Graph 2 shows the Case-Shiller U.S. national house price index expressed in constant dollars. Quite a similar pattern of going up a lot and then going down as much.

The mortgage lending excesses essential to the housing bubble reflected, in part, a mania of politicians to drive up the U.S. homeownership rate. The pols discovered, so they thought, how to do this: make more bad loans—only they called them, “creative loans.” The homeownership rate did rise significantly—and then went back down to exactly where it was before. Another instructive symmetrical round trip, as shown in Graph 3.

The first symmetrical up and down played out in the course of three years, the second in 12 years, the third in two decades. Much longer patterns are possible. Graph 4 shows the amazing six-decade symmetry in U.S. long-term interest rates.

Is there magic or determinism in this symmetry? Well, perhaps the persistence of underlying fundamental trends and the regression to them shows through, as does the reminder of how very much prices can change. In the fourth graph, we also see the dangerous power of fiat currency-issuing central banks to drive prices to extremes.

Unfortunately, graphs of the past do not tell us what is coming next, no matter how many of them economists and analysts may draw. But they do usefully remind us of the frequent vanity of human hopes and political schemes.

The Federal Reserve is the bank most in need of a stress test

Published in Real Clear Markets.

Do you know a bank that is leveraged at more than 100:1-to be exact, with assets of 111 times its equity? You do: it’s the Federal Reserve.

The consolidated Federal Reserves banks had total assets of $4.47 trillion as of Dec. 14, 2016, compared to total capital of merely $40.4 billion, or less than 1 percent of assets-actually, 0.9 percent.

The largest Federal Reserve Bank by far, New York, sports $2.47 trillion in total assets and only $13 billion in total capital, for leverage of a pretty remarkable 190 times and a capital ratio of 0.53 percent.

The Fed enjoys imposing stress tests on everybody else. What if we give the Fed a stress test? The interest rate risk of the Fed is similar to a 1980s savings-and-loan – lots of long-term, fixed rate assets, with short funding. So let’s apply a simple and standard interest rate stress test. Suppose long-term interest rates rise by 2 percent, to a historically more normal level. What happens to the Fed?

Well, the Fed now owns $4.4 trillion of long-term, fixed-rate assets and unamortized premium paid. It does not disclose the duration of this massive position, but let’s say it’s five years (it could be longer). If interest rates rise by 2 percent, the market value loss to the Fed is approximately 5 times 2 percent or 10 percent of the $4.4 trillion position. That would be an economic loss of $440 billion. That is 11 times the Fed’s total capital.

It seems highly likely that the Federal Reserve System, and the Federal Reserve Bank of New York in particular, would then be hugely insolvent on a mark-to-market basis. Stress test score: F.

Defenders of the Fed confidently claim that it doesn’t matter if the Fed is insolvent. Maybe they are right. If they are, the Fed should have no hesitation at all in publishing the mark to market of its giant securities portfolio, the way the Swiss central bank is required to do. To the Fed Board of Governors: How about it?

Why current asset prices are dangerously exaggerated

Published in Real Clear Markets.

Over the long term, real per-capita household net worth in the United States has grown at about 2 percent a year. This is a wonderful achievement of the enterprising economy.

In shorter periods, when asset prices get inflated in a bubble, household per-capita wealth appears to rise notably above this long-term pace, but ultimately, bubble asset prices inevitably shrivel. When they do, many commentators claim that a lot of “wealth” been lost by households. It hasn’t, because the apparent wealth was not really there in the first place: it was an illusion of the bubble.

If any very great number of people try to sell out at the bubble prices, the evanescent “wealth” disappears, the bubble deflates and the long-term trend reasserts itself, so the aggregate bubble prices can never be realized. Bubble times reflect what Walter Bagehot so truly wrote in 1873: “All people are most credulous when they are most happy.”

Graph 1 is the record of 1953 to 2016. The temporary illusion of wealth represented by two remarkable bubbles of recent decades is obvious.

We should recall with amused irony that the central bankers formerly congratulated themselves for creating what they credulously called “The Great Moderation.” What they actually presided over was the Era of Great Bubbles: first the Great Overpaying for Tech Stocks in the 1990s, then the Great Overleveraging of Real Estate in the 2000s.

And now? They are congratulating themselves again for innovative or radical monetary actions, including their zero interest rate policy (ZIRP), which expropriates the returns to savers and makes the present values of assets rise. Many observers, including me, think they have by their manipulations inflated new bubbles in stocks, bonds and houses. This has put real household wealth per-capita measured at current asset prices back over its 2 percent growth line, although not as egregiously as in the government-promoted housing bubble of the last decade. We can expect ultimate regression to the trend, as always.

But has the trend shifted? From 1950 to 2000, growth in U.S. real per-capita gross domestic product averaged more than 2 percent per-year. This is consistent with a 2 percent growth in wealth per-capita. But since 2000, real per-capita GDP has grown less than 1 percent per-year. Suppose the stagflationists are right, and this represents not a temporary, but a sustained downshift. Then it would be consistent with real per-capita economic growth to move our trend growth in real net worth per-capita down to 1 percent. Graph 2 shows the possible new trend line, starting in 2000.

If we measure from this new line, the current ZIRP bubble looks much worse; it has reached almost the same magnitude as the infamous housing bubble of a decade ago.

Graph 3 shows the variation from the 2 percent and 1 percent lines, displaying the illusory household wealth effects of the series of bubbles in a different fashion.

The more you believe the stagflationist theory, the more you must conclude that current asset prices are dangerously exaggerated, the greater the bubble you must conclude that the central bank experiments have wrought and the further we have to fall back to the trend.

The Credit Crunch of 1966: An instructive 50th anniversary

Published in Real Clear Markets.

It’s the 50th anniversary of the Credit Crunch of 1966, which roiled financial markets in August and September of that year. Group financial memory fades, so if you don’t know or remember that there was such a crunch, searing at the time, you are not alone. Yet it taught an essential lesson, again being relearned right now, 50 years later: the Federal Reserve, and central banks in general, simply do not know what the right interest rate is.

Central to the events of 1966 was that the Federal Reserve set the maximum interest rates that banks could pay on their deposits. This was the Fed’s now long-gone but then critical “Regulation Q” authority, at the time considered an essential part of the banking system.

As of July 1966, the Fed had set the interest-rate ceiling on savings deposits at 4 percent. For so-called “multiple maturity” time deposits (where withdrawal was at the depositor’s notice) it was 4 percent for a minimum maturity of up to 89 days, and 5 percent for 90 days or more. For fixed-maturity date time deposits, the ceiling was 5.5 percent. In September 1966, it dropped to 5 percent, except that deposits of more than $100,000 (that’s $743,000 in 2016 dollars) could still get 5.5 percent.

How did the Fed know those numbers were right? It didn’t, as events demonstrated. Most of the time over the preceding decades, they had set the ceiling over market rates, so it generally hadn’t been an issue.

But in 1966, there was strong credit demand from an extended economic expansion, plus inflationary pressure from the Vietnam War and “Great Society” deficits. Interest rates in the open market went much higher than before. Three-month Treasury bill yields got to 5.59 percent, the federal funds rate to 5.77 percent and commercial paper rates to 6 percent. Market rates on negotiable CDs went over the ceilings. “The prime rate briefly reached the then unheard of level of 6 percent,” wrote economist Albert Wojnilower. A 6 percent prime rate was the highest it had been in more than 30 years.

This time, the Fed refused to raise the ceiling in line with the market, in part reflecting political pressure to limit competition for deposits in order to favor savings-and-loan institutions, which were stuck with long-term mortgages at low fixed rates. Lending long and borrowing short was already dangerous in 1966.

Naturally, in response, people took their money out of both banks and savings and loans and put it into higher-yielding conservative investments, a perfectly sensible thing to do. This process had a cumbersome name at the time: “disintermediation”—a problem created entirely by regulation. Unable to expand their funding, the banks cut back on their loans. The savings and loans cut way back on their mortgage loans. “For most people, residential mortgage money was unobtainable…there was a sharp slump in mortgage loans and housing starts,” wrote The New York Times.

Banks also cut back on their previously expanding investments, notably in municipal bonds. Both banks and thrifts worried about their ability to fund their existing balance sheets. As described by the theoretician of financial crises, Hyman Minsky: “By the end of August, the disorganization in the municipals market, rumors about the solvency and liquidity of savings institutions, and the frantic [funding] efforts by money-center banks generated what can be characterized as a controlled panic.” Not allowed to bid competitive rates for deposits, as the St. Louis Fed’s history of the credit crunch reports: “Banks had never before experienced a large outflow of time deposits.”

So the Fed fixed prices and the result was the credit crunch. Following Wojnilower’s lively account: “Lending to all but the most established and necessitous customers was halted abruptly. Chief executives of leading banks reportedly were humbled to the point of pleading with their counterparts in industry to renew their CDs.” Further, in order to the raise needed funds, there was “the apparent inevitability of massive distress sales of long-term assets into a paralyzed marketplace.”

Who came to the rescue? The cause of the problem. “The gravity of the situation penetrated to an initially incredulous Federal Reserve,” Wojnilower continues. Banks were invited to borrow at the discount window in the face of “the very lively fears that major banks might have to close their doors.”

The shock of the credit crunch led the Fed into “a long-lasting series of private and public reassurances that no such crisis would ever be permitted to recur.” How did that work out? Three years later came the more severe credit crunch of 1969. As economist Charlotte E. Ruebling wrote at the time, “market interest rates have soared to levels never before reached in this country,” but “rates on deposits at banks and other financial institutions have been held much lower.” By the Fed, of course.

The authors of Regulation Q had a really bad idea, based on the false assumption that the Fed would somehow know the right answer. But the Fed did not know what the right interest rate was in 1966, or 1969—nor do they know it now. They never have and cannot know it. Put not your faith in their dubious “expertise.”

Negative rates aren’t working. Why do central banks persist?

Published in Real Clear Markets with Paul Kupiec.

Monetary policies in Europe and Japan have produced trillions of dollars of bonds with negative nominal interest rates in the hope of stimulating economic growth. Indeed, the Bank of Japan’s recent policy announcement doubles-down on this strategy by pledging to cap 10-year Japanese government bond yields at zero until the central bank hits its 2 percent inflation target.

But there is little evidence that negative interest rates are stimulating economic growth. Economic data suggest that consumers are actually saving more in countries with negative interest rates. And business investment, far from being stimulated by near-zero borrowing costs, is weak across the board. It’s time for a critical reassessment of unconventional post-crisis monetary policy experiments.

A typical consumer’s lifecycle has three phases – a borrowing phase, a saving phase and a phase for consuming savings in retirement. The aging of developed countries has increased the economic importance of the latter two lifecycle phases. While negative real interest rates benefit borrowing households, they are a tax on savers and those in retirement.

With negative nominal interest rates, prudently sock away your income for years and you are certain to receive less money than you invested. On top of that, monetary authorities worldwide target perpetual inflation, so chances are that you will face a higher price level in the future. Faced with this double whammy, economists predict that consumers should spend rather than save, but the data strongly suggest that households are compensating for negative interest rates by saving more, not less.

Recent OECD data show that, as average short-term interest rates turned negative, household savings rates increased in Switzerland, Germany, Sweden, Denmark and Japan. The OECD forecasts decade-high household savings rates in 2016 for all these countries except Japan.

Recent negative and near-zero interest rate policies have also had unanticipated impacts on business investment. If businesses followed economic textbooks, they would invest in activities that are profitable when expected revenues and costs are discounted using their average cost of funds. Under this decision rule, investment should increase when monetary policies force interest rates to zero or below, because more investments are profitable when a business’ cost of borrowing falls.

But many business mangers apparently skipped this economics lecture. Research has shown that many firms evaluate investments by discounting future cash flows using a management-set hurdle rate, not their firm’s cost of raising new funds. Survey evidence finds that firms set investment hurdle rates between 12 to 15 percent for investments similar to their existing business lines, and significantly higher for new business ventures.

Moreover, the evidence from multiple countries suggests that business hurdle rates are “sticky” over time. Firms do not appear to adjust their hurdle rates in response to changes in short-term interest rates. For example, a recent Federal Reserve Board study concludes that business investment hurdle rates have changed little since the 1980s, despite nearly double-digit declines in corporate borrowing costs.

The missing piece in the business investment puzzle is uncertainty. When businesses perceive high downside risks, they wait to invest. The delay allows firms to acquire new information and avoid potential downside losses by postponing investing until the data confirm an improved outlook. This behavior mimics the Federal Reserve and other monetary authorities’ habit of delaying action until additional data confirm the underlying economic trend.

The option to wait has the potential to put a huge drag on business investment. When monetary authorities use highly publicized, radical approaches like QE and negative interest rates and justify the policies as “insurance” against a deflationary spiral, they are themselves creating uncertainty. The more monetary authorities push the negative interest rate frontier to save their economies from disaster, the bigger the uncertainty they telegraph to businesses and consumers about downside risks.

Against mounting evidence, it is becoming harder to cling to the theory that near-zero and negative interest rates stimulate economic growth. When rates are negative, savers appear to save more, not less; retirees consume less to conserve their nest eggs; and business investment stagnates, as the value of the option to wait for an improved economic outlook grows.

But near-zero and negative interest rates do have one beneficiary – governments. Near zero and negative nominal rates reduce budget deficits because governments borrow virtually for free or even get paid to issue debt. So although near-zero and negative interest rates cloud the outlook for economic growth, these monetary policies have provided a silver lining for treasuries and finance ministries.

Taking on Leviathan

Published in the Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679), the great philosopher of the authoritarian state, in a famous metaphor portrayed the government as a dominating giant or Leviathan, animated by absolute sovereignty, and passing out rewards and punishments as it saw fit. It alone could control the unruly passions of the people and create stability and safety.

Today’s “administrative state”—or government bureaucracy, acting simultaneously as sovereign legislator, executive, and judge—brings Hobbes’ image of the giant vividly to mind.Nowhere is his metaphor more apt than in the government’s attempts at “systemic financial stability.” Hobbes’ 21st century acolytes include former Senator Chris Dodd (D-Conn.) and former Congressman Barney Frank (D-Mass.), whose Dodd-Frank Act sought to prevent financial crises, as Hobbes sought to prevent civil wars, by enlarging the giant. Now, as then, how to control the unruly passions, lust for power, and misguided enthusiasms of the state itself is left unanswered.

However, Congressman Jeb Hensarling (R-Tex.), who chairs the House Financial Services Committee, is now taking on Leviathan in the financial system with the proposed Creating Hope and Opportunity for Investors, Consumers and Entrepreneurs (CHOICE) Act. If it seems unlikely that he could fell the giant altogether, perhaps he could limit and better control and confine it, at least with respect to banking and the people’s money. If he succeeded, the federal government would place more emphasis on competitive markets and less on the diktats of the central bank and regulatory bureaucrats whom Dodd-Frank made sovereign.

Writing his book Leviathan in 1651, in the wake of the English Civil War and the beheading of King Charles I, Hobbes had this to say: “By art is created that great LEVIATHAN called a COMMONWEALTH or STATE (in Latin, CIVITAS), which is but an artificial man, though of much greater stature and strength.”

He went on:

sovereignty is an artificial soul, as giving life and motion to the whole body; the magistrates and other officers of judicature and execution, artificial joints; reward and punishment (by which fastened to the seat of the sovereignty, every joint and member is moved to perform his duty) are the nerves.

Moreover,

Salus Populi (the people’s safety) its business; counsellors, by whom all things needful to know are suggested unto it, are the memory; equity and laws, an artificial reason and will; concord, health; sedition, sickness; and civil war, death.

Writing four decades before the founding of the Bank of England, Hobbes can be forgiven for not mentioning the central bank, which has since become a key element of sovereignty. We need to extend his metaphor to include it. We could say that the central bank is a kind of artificial heart pumping the circulating blood of credit and money, making sure to lend the government as much as it wants. It often pumps this blood of credit to an excessive extent, causing financial markets to inflate, be overly sanguine, then bust, constrict their flows and suffer the heart attacks of financial panics.

Three centuries or so after Hobbes, Leviathan developed a new capability: that of constructing vast shell games guaranteeing huge quantities of other people’s debt and taking vast financial risks, while pretending that it wasn’t doing this, and keeping this debt off the books. I refer to the invention of government-sponsored enterprises like Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, and to related schemes such as government-sponsored insurance companies, like the Federal Savings and Loan Insurance Corporation and the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation. All serve as Leviathan’s artificial stomach and gluttonous appetite for risk, causing in time obesity, flatulence, indigestion, and finally the heartburn of publicly admitted insolvency.

Although financial panics temporarily render Leviathan stunned and confused, in short order it resumes its energetic activity and ambitious pursuit of greater power. Writing legislation in 2010, in the wake of the financial crisis of 2007 to 2009, Senator Dodd and Representative Frank ordered Leviathan to make deep expansions into the financial sector. The people’s financial safety and concord became defined as a new supreme demand for “compliance” with the orders of government bureaucrats, who were assumed to know the right answers.

The Dodd-Frank Act was passed in 2010 on party line votes at a time of insuperable Democratic majorities in both houses of Congress. Shortly after voting it in, the Democrats suffered stinging losses in that year’s congressional elections. No subsequent Congress would ever have dreamed of passing anything remotely resembling Dodd-Frank, but financial Leviathan had already been put on steroids and unleashed.

Now comes Chairman Hensarling to try to bring financial Leviathan back under control. The CHOICE Act would reform Leviathan’s activity in a wide swath of financial areas. It would:

Remove onerous Dodd-Frank burdens on banks that maintain a high tangible capital ratio (defined as 10 percent of total assets), thus creating a simple rule instead of the notoriously complex ones now in force.

Force the Financial Stability Oversight Council into greater transparency by cutting back the power of this committee of regulators to make opaque decisions in secret.

Correct the egregiously undemocratic governance of another bureaucratic invention, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, by giving it a bipartisan board and subjecting it to the congressional oversight and appropriations process that every federal agency should have.

Require greater accountability and transparency from Leviathan’s heart, the Federal Reserve.

Require cost-benefit analysis for new regulations and a subsequent measurement of whether they achieved their goals—imagine that!

Repeal the “Chevron Doctrine” that leads judges to defer to federal agencies. This is essential, as bureaucrats make ever-bolder excursions beyond their legal authority.

Take numerous steps to relieve Leviathan’s heavy hand on small businesses and small banks.

The CHOICE Act will likely be taken up by the House Financial Services Committee this fall—and be ready for further consideration if, as is forecast by most people, Republicans retain control of the House of Representatives in the upcoming election. The debates about the bill will be contentious and sharply partisan, with vehement opposition from those who love Leviathan. How far the reform bill can go depends on how other parts of the election turn out.

Will financial Leviathan grow ever fatter, more arrogant, and more intrusive? Or can it be put on a long-term diet by constraining its arrogance, correcting its pretensions, imbuing its artificial soul with behavior befitting a republic, and put in the service of a limited government of checks and balances?

The CHOICE Act is a good start at this daunting and essential project.

The new century brings remarkable downshift in per-capita GDP growth

Published in Real Clear Markets.

For the half-century from 1950 to 2000, U.S. real gross domestic product per capita grew at an average rate of 2.22 percent per year. For the first 15 years of the 21st century so far, this key measure of the overall standard of living has grown, on average, at only 0.89 percent.

Of course, a growth rate per person of 0.89 percent is still growth, and growth in output per person sustained over years is still a notable achievement of the market economy.

But the difference between growth rates of something over 2 percent and a little less than 1 percent is a very big deal. How much difference does that drop make, if it continues? Thanks to the always-surprising power of compound growth rates over time, the difference in the resulting long-term standard of living is huge.

In a lifetime of 80 years, for example, per capita GDP growth of 0.89 percent per year will double the economic standard of living-on average, people will become twice as well off as before. But with a growth rate of 2.22 percent, GDP per capita will more than quintuple in the same 80 years-people will be five times as well off. Such amazing improvement has actually happened historically beginning with the economic revolutions of the 19th century and continuing through the 20th. In 1950, U.S. real per capita GDP was $14,886 (using constant 2009 dollars). By 2000, it was $44, 721-thus 3X in 50 years.

The downshift of our new century is apparent when we look at the average growth rates in successive 15-year periods, as shown in the table.

Why the downshift and will it continue? The answer, as with so many things in economics, is that we do not know.

One theory now proposed is “secular stagnation.” This is not really so much a theory as giving a different name to slower growth rates. “Stagnation” was also a noted economic assertion in the 1940s– just before the postwar boom and on the verge of 50 years of solid growth. The great economist, Joseph Schumpeter, writing in 1949 on “modern stagnationism,” observed that “stagnationist moods had been voiced, at intervals, by many economists before.” Now they are being voiced again. They were always wrong before. Will they be right this time?

Among the factors we may speculate contribute to the markedly slower growth in real per capita GDP of this century are: the drag from financial crises and their resource misallocations; the aging of the population, with lower birth rates and long retirements; the fall in labor participation rates, so there are fewer producers as a percent of the population; the ever-more oppressive tangle of government regulations, so that “compliance” with the orders issued by bureaucrats becomes the top priority; and the massive monetary distortions of central banks, pretending to know what they are doing.

Can all this continue to suppress the underlying growth dynamic of scientific advance, innovation, entrepreneurship and enterprise of a market economy? Unless the government interventions get a lot worse (which they may!), I believe the current stagnationists will likely join their historical predecessors among the ranks of the false prophets. Let us hope so.

‘Commercial’ bank is misnomer. ‘Real estate’ bank is more apt

Published in American Banker.

Comparing banking in the 1950s to today, we find giant changes that surely would have astonished the bankers of that earlier time. What’s the biggest and most important one?

You might nominate the shrinkage in the total number of U.S. banks from over 13,200 in 1955 to only about 5,300 now — a 60 percent reduction. Or you might say the rise of interstate banking, or digital technology going from zero to ubiquitous, or the growth of financial derivatives into hundreds of trillions of dollars, or even air conditioning making banking facilities a lot more pleasant.

You might point out that the whole banking industry’s total assets were only $209 billion in 1955, less than one-tenth the assets of today’s JPMorgan Chase, compared with $15 trillion now. Or that total banking system equity was $15 billion, less than 1 percent of the $1.7 trillion it is now. Of course, there have been six decades of inflation and economic growth. The nominal gross domestic product of the United States was $426 billion in 1955, compared with $17.9 trillion in 2015. So banking assets were 49 percent of GDP in 1955, compared with 83 percent of GDP now.

But I propose that the biggest banking change during the last 60 years is none of these. It is instead the dramatic shift to real estate finance and thus real estate risk, as the dominant factor in the balance sheet of the entire banking system. It is the evolution of the banking system from being principally business banks to being principally real estate banks.

In 1955, commercial and industrial loans were 40 percent of total banking loans and real estate loans only 25 percent. The great banking transition set in after 1984. The share of C&I loans kept falling, down to about 20 percent of total loans, while real estate loans rose to about 50 percent, with a bubble-induced peak of 60 percent in 2009. In this remarkable long-term shift, the share of real estate loans doubled, while the share of commercial and industrial loans dropped in half. The lines crossed in 1987, three decades ago and never met again, despite the real estate lending busts of the early 1990s and of 2007-9.

The long-term transition to concentration in real estate would have greatly surprised the authors of the original National Banking Act of 1864, which prohibited national banks from making any real estate loans at all. This was loosened slightly 1913 by the Federal Reserve Act and significantly in 1927 by the McFadden Act — in time for the ill-fated real estate boom of the late 1920s.

The real estate concentration is even more pronounced for smaller banks. For the 4,700 banks with assets of less than $1 billion, real estate loans are 75 percent of all loans, about the same as their bubble-era peak of 76 percent.

Moreover, in another dramatic change from the 1950s, the securities portfolio of the banking system has also become heavily concentrated in real estate risk. Real estate securities reached 74 percent of total banking system securities at the height of the housing bubble. They have since moderated, to 60 percent, but that is still high.

In terms of both their lending and securities portfolios, we find that commercial banks have become basically real estate banks.

Needless to say, this matters a lot for understanding the riskiness of the banking system. The assets underlying real estate loans and securities are by definition illiquid. The prices of these assets are volatile and subject to enthusiastic run-ups and panicked, unexpected drops. When highly leveraged on bank balance sheets, real estate over banking’s long history has been the most reliable and recurring source of busts and panics.

A good example is the frequency of commercial bank failures in 2007-12 relative to their increasing ratio of real estate loans to total loans at the outset of the crisis in December 2007. From the first quartile, in which real estate loans are less than 57 percent of loans, to the third quartile, in which they are over 72 percent, the frequency of failure triples, and failures are nine times as great for the highest ratio quartile as for the lowest. In the fourth quartile, real estate loans exceeded 83 percent of loans, and the failure rate is over 13 percent, which represents 60 percent of all the failures in the aftermath of the bubble. The 50 percent of banks with the highest real estate loan ratios accounted for 82 percent of the failures.

Central to the riskiness of leveraged real estate is the risk of real estate prices falling rapidly from high levels — and right now those prices are again very high. The Comptroller of the Currency’s current “Risk Perspective” cites rapid growth in commercial real estate loans, “accompanied by weaker underwriting standards” and “concentration risk.”

The predominance of real estate finance in banking’s aggregate banking balance sheet makes that risk far more important to the stability of the banking system than the bankers of the 1950s could ever have imagined.

Who will pay for the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corp.’s huge losses?

Published in Real Clear Markets.

The government’s pension insurance company, the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation (PBGC), is broke. Because its creditors can’t demand their money immediately, it won’t have spent

its last dollar for “a significant number of years” yet (maybe ten) — but its liabilities of $164 billion are nearly twice its assets of $88 billion: there is no way it can honor all its obligations.

The PBGC has two programs, one insures single employer pensions and the other multiemployer, union-sponsored pensions. Both are insolvent, but the multiemployer program is in far worse shape: it is well and truly broke. Its liabilities of $54 billion are 27 times its assets of $2 billion. There are on top of that “reasonably possible” losses of another $20 billion.

The PBGC was supposed to be, according to its charter act, financially self-supporting: obviously it isn’t. Also according to the act, its liabilities are not obligations of the United States government: but it couldn’t continue to exist even for a minute except as part of the government. Will the taxpayers end up paying for its losses-or if not, who?

A month ago (June 17, 2016), Labor SecretaryThomas Perez, who chairs the PBGC board, wrote disingenuously to the Congress, that the board wants to work with Congress “to ensure the continued solvency of the multiemployer program.” A forthright statement would have been: “to address the disastrous insolvency of the multiemployer program.”

In the background of the PBGC’s huge net worth deficit are a large number of deeply underfunded multiemployer pension funds. “Overall,” Perez’s letter admitted, “plan assets in the multiemployer pension system are now less than half of earned benefits.” You could call that underfunding with a vengeance.

An instructive example is the Central States plan (formally, the Teamsters union’s Central States, Southeast and Southwest Areas Pension Fund). The financial stress of this large and utterly insolvent multiemployer plan brings the inescapable problems into sharp focus. As an officially “critical and declining” multiemployer pension plan, Central States was able under the Kline-Miller Multiemployer Pension Reform Act of 2014, to submit a plan, which ran to 8,000 pages, to reduce its pension obligations to a level more in line with its assets and income. The reduced pensions under this proposal, consistent with the 2014 act, would still have been higher than if the fund went into the PBGC.

The U.S. Treasury Department rejected the proposed plan, pointing out various technical shortcomings and the hard fact that even with the pension reductions, the proposal did not fix Central States’ long-term insolvency-which is indeed a requirement included in the 2014 act (put in, apparently, at the insistence of the Democratic legislators). This has the ironic result, as the Washington Post editorialized, that “if Central States collapses and the PBGC takes over, retirees would, by law, get even less than they would under the just-rejected proposal.” And that is assuming that the PBGC itself can pay its obligations over time, which it can’t.

Some observers have suggested that the Treasury’s motivation was political rather than technical. In other words, that the incumbent administration could not afford to approve any reduction, even if a better deal than the PBGC would provide, in the pension benefits of a union-sponsored pension plan, no matter how broke that plan is.

Of course, the Treasury’s action leaves Central States just as broke as it was before, the multiemployer pension system just as hopelessly underfunded as it was before, the PBGC’s multiemployer program just as broke as it was before, and the overall PBGC the same.

Let’s consider the fundamental truths. The money needed to pay the pension obligations of Central States was simply not put into the pension fund, so it’s not there to pay them. The money needed to pay the pension obligations of the multiemployer pension system as a whole was simply not put into the funds, so it’s not there to pay them. The insurance premiums needed to make the PBGC able to honor its insurance obligations were not set at the necessary levels and were therefore not collected, so it is not there to pay them.

The resulting deficits are huge and real. Someone is consequently going to suffer the losses which are unavoidable because they have already happened. Who is that someone?

There are multiple candidates for taking or sharing in the losses:

1. The pension beneficiaries who have claims on insolvent pension plans. Their pensions could be reduced, as in the Detroit bankruptcy, or if they are still working, their own contributions to the pension plans significantly increased, or both. Also, they might start paying individual insurance premiums to the PBGC, just as government-insured mortgage borrowers pay individual premiums to the Federal Housing Administration.

2. The employers who unwisely committed to pension plans whose benefits have proved unpayable. They could make much bigger contributions to funding the plans, or pay vastly higher insurance premiums to the PBGC, or both.

3. The union sponsors of the multiemployer plans. They could be removed from any control of insolvent multiemployer plans, in effect putting such plans into PBGC receivership, as in a normal insolvency proceeding and as with failed single employer pension plans. There is no reason for multiemployer plans to be different. But as it is now, the PBGC merely pays the tab for failed multiemployer plans.

4. The creditors of employers. The deficit of a pension plan is an unsecured creditor’s claim on the employer. That could be made a senior claim, just as deposits were made senior claims on banks after the financial crisis of the 1980s. This would force some of the burden on to other creditors of failed employers.

5. Taxpayers. It is inevitable that a taxpayer bailout will be proposed, despite the pious statutory assurance that PBGC’s debts are not government obligations. Against this proposal, it will be fairly asked why people with no pensions themselves or who don’t have defined benefit pensions should pay for those who do have them-a good question. On the other side, the hardship of existing pensioners of insolvent pension funds will be sincerely urged.

6. Some combination of the above.

Needless to say, whoever ultimately has to take the unavoidable losses will not like it.

Consider this striking historical parallel to the probable fate of the PBGC’s multiemployer program: the decade-long descent into humiliating failure of the government’s deposit insurer, the Federal Savings and Loan Insurance Corporation (FSLIC). This government insurer, along with the savings and loan industry whose obligations it guaranteed, sank into a sea of insolvency in the 1980s. When this finally had to be publicly confessed, FSLIC became notorious. It certainly seems that the PBGC is the new FSLIC.

In tracking homeownership, marriage matters

Published in Real Clear Policy with Jay Brinkmann.

Homeownership long has been considered a key metric for economic well-being in the United States. Thus, many are dismayed by the fact that, at 63.5 percent, the 2015 overall homeownership rate appears to be lower than the 64.3 percent of 1985, a generation ago. But viewed in another, arguably more relevant way, the underlying trend shows the homeownership rate is, in fact, increasing, not decreasing.

How so? Key to the trend is the extremely strong relationship between marriage and homeownership — a relationship seldom, if ever, addressed in housing-finance discussions. But if you think about it, it’s obvious that homeownership should be higher among married couples than among other households; in fact, it’s remarkably higher.

This relationship holds across all demographic groups. Importantly, it means that changes in the proportion of married versus not-married households is a major driver of changes in the overall homeownership rate over time. Homeownership comparisons among demographic groups are similarly influenced by differences in their respective proportions of married versus not-married households.

Policy discussions over falling homeownership rates frequently ignore some critical underlying demographic facts.

The current 63.5 percent American homeownership rate combines two very different components: married households, with about 78 percent homeownership, and not-married households, with only 43 percent homeownership. Married households have a homeownership rate 1.8 times higher — obviously a big difference. (As we have organized the data, these two categories comprise all households: “married” means married with spouses present or widowed; “Not-married” means never married, divorced, separated or spouse absent.)

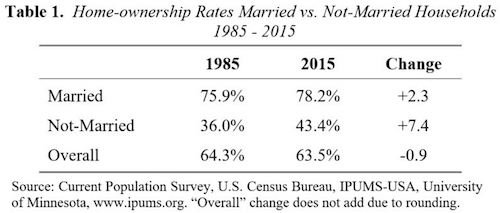

Table 1 contrasts homeownership by married versus not-married households, showing how these homeownership rates have changed since 1985.

One is immediately struck by a seeming paradox:

The homeownership rate for married households has gone up by 2.3 percentage points.

The homeownership rate for not-married households has gone up even more, by 7.4 percentage points.

But the overall homeownership rate has gone down.

How is this possible? The answer is that the overall homeownership rate has fallen because the percentage of not-married households has dramatically increased over these three decades. Correspondingly, married households (which have a higher homeownership rate) are now a smaller proportion of the total. Still, homeownership rose for both component parts. So the analysis of the two parts gives a truer picture of the underlying rising trend.

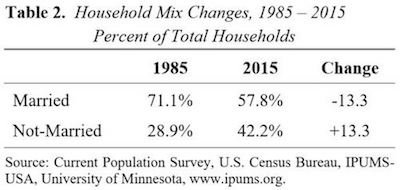

The dramatic shift in household mix is shown in Table 2.

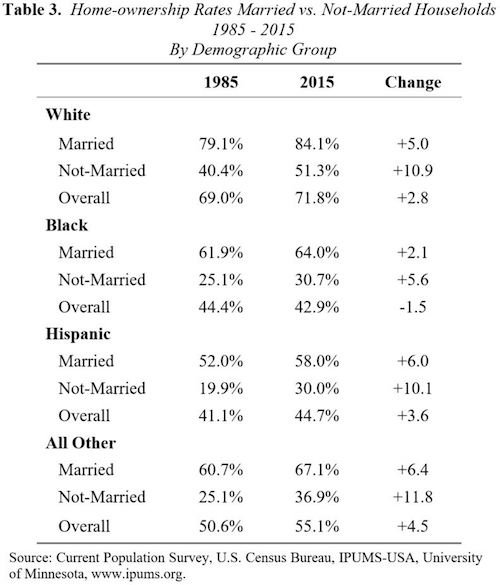

Table 3 shows that the strong contrast between married and not-married homeownership rates and related changes from 1985-2015 hold for each demographic group we examined.

That is, homeownership for both married and not-married households went up significantly for all four demographic groups from 1985 to 2015.

Moreover, overall homeownership also increased for three of these four groups. Homeownership for black households, meanwhile, fell by 1.5 percentage points, though homeownership for both married and not-married components rose for this demographic as well. (This is consistent with that group’s showing the biggest shift from married to not-married households.)

In another seeming paradox, Hispanic homeownership rates rose, while still contributing to a reduction in the overall U.S. rate. The reason for this is that their share of the population more than doubled, increasing the weight of their relatively high share of not-married households.

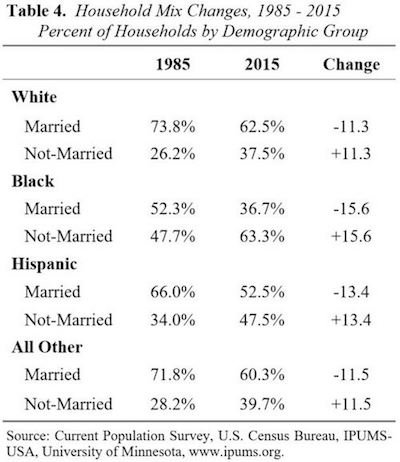

The trends by group in the mix of married versus not-married households are shown in Table 4.

What would the U.S. homeownership rate be if the proportions of married and not-married households were the same as in 1985? Applying the 2015 homeownership rates for married and not-married households to the mix that existed in 1985 results in a pro forma U.S. homeownership rate of 68.1 percent. This would be significantly greater than both the 1985 level of 64.3 percent and the 2015 measured level of 63.5 percent.

Adjusting for the changing mix of married versus not-married households gives policymakers a better understanding of the underlying trends. This improved understanding is particularly important when weaker credit standards are proposed as a government solution to the lower overall homeownership rate.

To make sense of homeownership rates, we have to consider changes in the mix of married versus not-married households. And these changes have been dramatic over the last 30 years.

The perfect antidote to Dodd-Frank

Published in American Banker.

To overhaul the Dodd-Frank Act, here is a radical and really good idea from House Financial Services Committee Chairman Jeb Hensarling, R-Texas.

The Financial CHOICE Act, Hensarling’s bill, says to U.S. banks: “Don’t like the endless additional regulation imposed on you by the bloated Dodd-Frank Act? Get your equity capital up high enough and you can purge yourself of a lot of the regulatory burden, deadweight cost and bureaucrats’ power grabs – all of which Dodd-Frank called forth.”

This Choice bill, which stands for Creating Hope and Opportunity for Investors, Consumers and Entrepreneurs, is not an order to increase your capital. Rather, it’s offering a logical choice.

Option 1: Put enough of your equity investors’ own money in between your creditors and the risk that other people will have to bail them out if you make big mistakes. And you may. Then, the government can’t claim you live on the taxpayers’ credit, and therefore, can’t justify its inherent urge to micromanage.

Option 2: Don’t get your equity capital up high enough and live with the luxuriant regulation instead. Think of this scenario as the imposed cost of using the taxpayers’ capital instead of your own to support your risks.

Depending on how large the explicit costs and the opportunity costs of the regulation are, you might think that the second option will yield higher returns on equity than option one or you might not. Some banks would choose one option, while some would choose the other.

Different choices would create diversification in the banking sector. They would also create highly useful learning over time. One group would end up sounder and make greater contributions to economic growth and innovation. One group would, over time, prosper more than the other.

Of course, we have to answer: how high is high enough? The 10 percent tangible leverage capital required to get the deal in the proposed legislation is a lot more than now, but is it even enough?

To consider the matter first in principle: surely, there is some level of equity capital at which this trade-off makes sense, some level at which everyone — even habitual lovers of bureaucracy — would agree that the Dodd-Frank burdens would be superfluous, or at least, cause costs far in excess of their benefits.

What capital ratio is exactly right can be, and is, disputed. Because government guarantees, mandates and interventions are so intertwined with today’s banks, there is simply no market answer available. Numerous proposals, based on more or less no data, have been made. The fact that no one knows the exact answer should not, however, stop us from moving in the right direction.

Among various theories, economist and New York Times columnist Paul Krugman proposed a maximum assets-to-capital ratio of 15:1, which means a minimum leverage capital ratio of 6.7 percent. Anat Admati, a Stanford finance professor, and Martin Hellwig, an economics professor at the University of Bonn, argued for a 20 percent to 30 percent leverage capital requirement with no empirical analysis. Economists David Miles, Jing Yang and Gilberto Marcheggiano estimated that the optimal bank capital is about 20 percent of risk-weighted assets, which in their view means 7 percent to 10 percent leverage capital, in a white paper. A group of 20 academics from finance and banking specializations suggested in a letter to the Financial Times a 15 percent leverage capital requirement. Economists Anil Kashyap, Samuel Hanson and Jeremy Stein proposed 12 percent to 15 percent risk-weighted, which means about 6 percent to 8 percent leverage capital. Professor Charles Calomiris suggested 10 percent leverage capital. Economist William Cline estimated the optimal leverage capital ratio at 6.6 percent to 7.9 percent. Robert Jenkins, a member of the financial policy committee at the Bank of England, gave a speech to the Worshipful Company of Actuaries entitled “Let’s Make a Deal,” where the deal was the “rollback of the rule book” in exchange for raising “equity capital to 20 percent of assets.” In my opinion, the 10 percent tangible leverage capital ratio in Hensarling’s bill is a fair stab at it.

In exchange for 10 percent leverage capital, it is essential to understand that the deal is not to eliminate all regulation. Indeed, there would still be plenty of regulation for banks taking the deal. However, option one is a distinctly better choice than the notorious overreaction and overreach of Dodd-Frank. In exchange for a further move to 20 percent leverage capital, one would rationally eliminate a lot more regulation and bureaucratic power.

It’s also essential to understand that the proposed capital ratio as specified in the Hensarling bill subtracts all intangible assets and deferred-tax assets from the allowable capital and adds the balance sheet equivalents of off-balance sheet items to total assets. Thus, it is conservative in both the numerator and denominator of the ratio.

In my judgment, the choice offered to banks by Chairman Hensarling’s proposal makes perfect sense. It goes in the right direction and ought to be enacted. Even the Washington Post editorial board agrees with this. In an op-ed, the editorial board writes:

More promising, and more creative is Mr. Hensarling’s plan to offer relief from some of Dodd-Frank’s more onerous oversight provisions to banks that hold at least 10 percent capital as a buffer against losses…such a cash cushion can offer as much—or more—protection against financial instability as intrusive regulations do, and do so more simply.

Very true!

The PBGC: A broke insurance company sponsored by your government

Published in Real Clear Markets.

Imagine an insurance company with assets of $88 billion, but liabilities of $164 billion. It has a huge deficit: a net worth of a negative $76 billion, and a capital-to-asset ratio of minus 87 percent.

Would any insurance commissioner anywhere allow it to remain open and to keep taking premiums from the public to “insure” losses it manifestly cannot pay? Of course not. Would any rational customer buy an insurance policy from it, when the company cannot even hope to honor its commitments? Nope.

But there is such an insurance company, open and in business and taking in new premiums for obligations it will not be able to pay. Needless to say, it is a government insurance company, since no private entity could continue in business in such pathetic financial shape. It is the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corp. (PBGC), a corporation wholly owned by the U.S. government, operating on an obviously failed model. Its board of directors comprises the secretaries of the departments of Labor, Commerce and the Treasury; quite a distinguished board for such egregious results.

There are two financially separate parts of the PBGC: the Single-Employer Program, which insures the defined-benefit pension plans of individual companies; and the Multiemployer Program, which insures union-sponsored plans with multiple companies making pension contributions. The Single-Employer Program has a large deficit, with assets of $86 billion, liabilities of $110 billion and a negative net worth of $24 billion. That is bad enough.

But now imagine an insurance company with assets of $2 billion and liabilities of $54 billion. That is a truly remarkable relationship. Its net worth is negative $52 billion, or 26 times its assets. That is the PBGC’s Multiemployer Program – which, as no one can doubt, is well on the way to hitting the wall.

The PBGC can continue to exist for only two reasons: because the government forces pension plans to buy insurance from it and because its political supporters entertain the abiding hope that Congress will somehow or another give it a lot of other people’s money to cover its unpayable obligations.

Congress should not do this, and so far, it has shown no inclination to announce a taxpayer bailout. But the real simultaneous financial and political crunch will occur when the disastrous Multiemployer Program runs out of cash while still being oversupplied with obligations. This moment is readily foreseeable, but has not yet arrived and is estimated to be a number of years off.

The PBGC was created by the Employment Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 (ERISA). This put into statue an idea created by the research department of the United Auto Workers union in 1961: let’s get the government to guarantee our pensions. The idea was politically brilliant but, financially, less brilliant.

According to the law, the PBGC was not supposed to be able to get itself into the insolvent status in which it not finds itself. As each PBGC Annual Report always informs us, “ERISA requires that PBGC programs be self-financing.” But they aren’t—not by a long shot, where the value of that long shot is at least $76 billion. What does the “requirement by law” to be self-financing mean when you aren’t and have no hopes to be so?

One thing originally intended to be quite clear we find in the next Annual Report sentence: “ERISA provides that the U.S. Government is not liable for any obligation or liability incurred by PBGC.” To repeat: Not liable. But of course, they said the same thing in statute about Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. They made Fannie and Freddie put that in bold face type on every memorandum offering their debt for sale. But they bailed out Fannie and Freddie anyway.

As it has turned out, the Fannie and Freddie bailout has proved to provide a positive investment return to the taxpayers: an internal rate of return of about 7 percent so far. But any bailout money put into the PBGC will be simply gone. It would not be an investment, but purely a transfer payment.

That reflects the fact that Fannie and Freddie, when their operations were not perverted by politically mandated excess risk, had a fundamental model capable of making profits, as they did before the housing bubble and now are again. This profit potential is not shared by the PBGC. Its fundamental model is to take politically mandated excess risk in order to promote unaffordable pensions, not to insure them according to rational actuarial principles.

Defined-benefit pension plans have proved beyond doubt to be an extremely risky financial construction. The idea that the government is guaranteeing them encouraged the negotiation of pensions unaffordable to the sponsors in the first place, and the underfunding of pension obligations later. These are the kinds of very costly moral hazards entailed in the very existence of the PBGC. Of course, the PBGC might have, had Congress allowed it to, charged vastly higher premiums. But this would be against the other of its assigned missions: to encourage and promote defined-benefit pensions.

You can understand how this was felt to be a nice idea, but it creates an irresolvable conflict for the PBGC. The corporation is simultaneously supposed to promote the use and survival of defined-benefit pension programs, while it is also supposed to run a sound, self-financing insurance company. Obviously, it has utterly failed at being a sound insurer. Arguably, by creating incentives to design unaffordable pensions, it also failed at promoting defined-benefit pension plans, and has rather accelerated their ongoing demise.

There is no easy answer to the PBGC problem as a whole, but Congress took a sensible and meaningful step with the Kline-Miller Multiemployer Pension Reform Act of 2014. We will devote the next essay to examining the implications of this act and the reasonable attempt to use it recently thwarted by the U.S. Treasury Department.

How high are real house prices?

Published in Real Clear Markets.

“Home prices are back to near-record highs across the U.S.” declared the Wall Street Journal in a June 1 front-page story. They are, indeed, when measured in nominal terms.

The Case-Shiller National House Price Index for the first quarter of 2016 is as high as it was in September 2005, in the late-phase frenzy of the bubble. That was only nine months before the 2006 bubble-market top, which as we know only too well, was followed by collapse. In addition to reaching its 2005 level, the National House Price Index has gone back to well over its trend line—more than 11 percent over. All this is shown in Graph 1.

So the Federal Reserve has gotten its wish for re-inflated house prices (although not its wish for robust economic growth).

Are high house prices good or bad? That depends on whether you are selling or buying. If you are the Fed, it depends on how much you believe that creating asset-price inflation leads to “wealth effects” that improve economic growth.

Of course, besides asset-price inflation, the Fed truly believes in regular old inflation. It has often announced its intent to create perpetual increases in consumer prices. Since the bubble top in 2006, the Consumer Price Index has increased by an aggregate of 17 percent.

This means that house prices – measured in real, inflation-adjusted terms – look different from Graph 1. Real house prices are shown in Graph 2, expressed in constant 2000 dollars. They have still gone up a lot in the last few years, but not as much as in nominal terms. They have matched their level from October 2003, rather than September 2005.

In October 2003, house prices were clearly inflating: they were half way, but only half way, up their memorable bubble run from 1999 to 2006. Do we remember how happy so many people were with those high house prices? Do we remember that the Fed Funds Rate had then been reduced to 1 percent? That the Fed was thinking of wealth effects? At the time (in January 2004), the Wall Street Journal published an article entitled, “Housing Prices Continue to Rise.” It reported that “the decline in interest rates has made housing more affordable,” that forecasts were for “the house party to rage on in 2004”—a good forecast— and that “few housing pundits see much risk of a national plunge in house prices”—a terrible forecast.

In 2003, was it time to pay attention? It was. Going forward from here, can we imagine what house prices would be with genuinely normalized interest rates? In mid-2016, can the pundits see much risk of anything going wrong?

Power, independence and guessing

Published in Library Of Law & Liberty.

The Power and Independence of the Federal Reserve is an informative and provocative history of the Fed and its remarkable evolution over a hundred years’ time: a complex institution, in a complex and changing environment.

Very importantly, author Peter Conti-Brown has included the Fed’s intellectual evolution, or the shifting of the ideas that shape its actions as these ideas go in and out of central banking fashion. This account makes readers wonder what new ideas and theories the leaders of the Fed will adopt, reinforce by groupthink with their fellow central bankers, and try out on us in future years.

As for the power wielded by the Fed, it has obviously come a very long way since its beginnings, when it was, as Conti-Brown describes it, “an obscure backwater government agency.” That is hard for today’s Americans to imagine. To illustrate the change, Conti-Brown relates the memorable story of when the new Federal Reserve Board went to President Wilson’s Secretary of the Treasury, William McAdoo, to complain that at a state function the board members were not given sufficient prominence in order of seating. McAdoo took the problem to Wilson. “Well, they might come right after the fire department,” replied the irritated President.

Little could he know that the Fed would become, in time, the global financial fire department, as part of being central bank to a world in which its fiat dollars were the dominant currency.

Of course the Fed has made, and doubtless will continue to make, great mistakes. Its enormous power, combined with its unavoidable human fallibility, renders it without question the most dangerous financial institution in the world—far and away the greatest potential creator of systemic financial risk there is.

Put that together with the other idea in Conti-Brown’s title: independence. He considers many factors affecting the independence the Fed so much wants and so energetically defends. He rightly emphasizes something as crucial as it is little-discussed: the Fed’s budgetary independence. The Fed, as Conti-Brown points out, is entirely free from the “power of the purse” normally exercised by Congress. Instead, it is able to spend whatever it wants out of the very large profits it automatically makes by issuing money, both the printed and the bookkeeping varieties. On the money-issuing and the spending, there is no constraint except its own decisions.

The more independent the Fed is, combined with its power and the huge riskiness of its actions, the bigger an institutional puzzle it represents in a government that was built on the principle of checks and balances.

In the famous conclusion of The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money (1936), John Maynard Keynes tells us that “soon or late, it is ideas . . . which are dangerous for good or evil.” This is true in general in human affairs, but it is especially true of the ideas that come, from time to time, to dominate the minds of central bankers—and most importantly, the central bankers who run the Fed. Conti-Brown’s tracing of the ideas of the Fed’s dominant personalities over time is key to understanding the institution.

For example, take the idea of fiat money. This was clearly not what the Fed would be about, in the minds of the authors of the Federal Reserve Act, like then-Chairman of the House Banking Committee, Carter Glass (D-Va.). Conti-Brown writes: “The claim that the new Federal Reserve Notes would represent ‘fiat money’ were fighting words.” He quotes Glass’s defense on the floor of the House of Representatives against the charge: “Fiat money! Why, sir, never since the world began was there such a perversion of terms.” But now the Fed is known by all to be the center and font of the worldwide fiat money system.

Or take inflation. Conti-Brown nicely summarizes the view of William McChesney Martin, Chairman of the Fed for 19 years and under five U.S. Presidents in the 1950s and 1960s: “The keeper of the currency is the one who has to enforce the commitment not to steal money through inflation.” But now the Fed has decided to commit itself to perpetual inflation and has for seven years been stealing money from savers through negative real interest rates—all for the greater good as embodied in its current theories and beliefs.

As Conti-Brown says, it is not the case that there are “objectively correct answers to problems of monetary policy . . . in a democracy.” That is why the Money Question, as impassioned historical debates called it, is always political and not merely technical. Central banking is, he writes, “plagued by uncertainty, model failures, imperfect data, and even central banker ideology.” (He should have left out that “even.”)

Conti-Brown views central bankers as “adjudicating between conflicting views of that uncertainty, those failures, these ideologies.” Quite right, except that he has a more optimistic view of the process than I do. In place of “adjudicating” among uncertainties, a more accurate term would be “guessing.”

This recalls a marvelous letter to the Financial Times of several years ago suggesting that “in mathematics, one answer is right; in literature, all answers are right; and in economics, no answers are right.” Conti-Brown says “it is tempting to throw out the entire enterprise of central banking as politics by another name.” But as he also says, this would not be right, either.

The key fact is that in central banking the uncertainty is high and, therefore, guessing is required. But the cost of mistakes can be enormous. This causes responsible minds to tend to cluster around common ideas and to reinforce each other by saying the same things. The book discusses this clustering in terms of “cognitive capture,” but I think a better description would be “cognitive herding.” This affects central bankers as it does everybody else when confronted with the need to decide and act in the face of ineluctable uncertainty.

In making decisions subject to uncertainty, metaphors are helpful, and Conti-Brown is fond of what he calls “the poetry of central banking”—that is, powerful figures of speech. The most famous such metaphor is that of Chairman Martin, who characterized the Fed as the “chaperone who has ordered the punch bowl removed just when the party was really warming up.” Martin (who studied English and Latin at Yale) “changed the language of central banking,” says Conti-Brown, and therefore its ideas. One can only imagine how surprised Martin would be that, in recent years, the chaperone has been the one pouring bottles of rum into the punch bowl to liven up the party.

Finally, on the subject of the Fed’s independence, Conti-Brown quotes Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke telling his successor, Janet Yellen, that “Congress is our boss.” But does the Fed as an institution really accept that as it insistently defends and pursues its independence? The more the Fed achieves practical independence from Congress, the more intriguingly alien to our fundamental Constitutional order it is.

Puerto Rico: A big default—what next?

Published in the Library Of Law And Liberty.

Rexford Tugwell, sometimes known as “Rex the Red” for his admiration of the 1930s Soviet Union and his fervent belief in central planning, was made governor of Puerto Rico by President Franklin Roosevelt in 1941. Among the results of his theories was the Government Development Bank of Puerto Rico, a bank designed as “an arm of the state,” which is a central element in the complicated inner workings of the Puerto Rican government’s massive insolvency.

The bank has just defaulted on $367 million of bonds – the first, but unless there is congressional action, not the last, massive default by the Puerto Rican government and its agencies on their debt. The Government Development Bank was judged insolvent in an examination last year, but the finding was kept secret. The governor of Puerto Rico has declared a “moratorium” on the bank’s debt, which means a default. A broke New York City in 1975 also defaulted and called it a “moratorium.”

Adding together the Puerto Rican government’s explicit debt of about $71 billion and its unfunded pension liabilities of about $44 billion amounts to $115 billion. This is six times the $18 billion in bonds and pension debt of the City of Detroit, which holds the high honor of being the largest municipal bankruptcy ever.

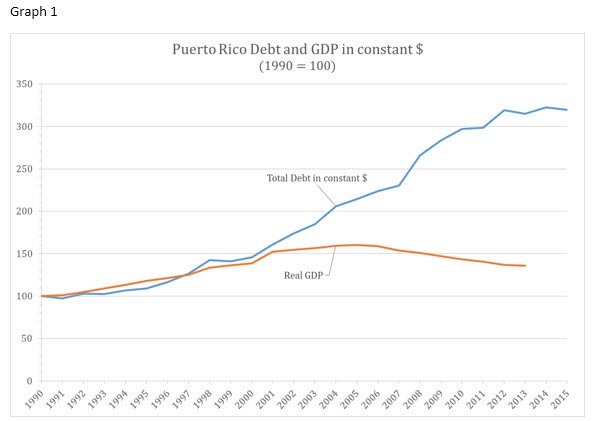

Puerto Rico’s government-centric political economy goes back to Rex the Red, but its budget problems are also long-standing. In this century, the government has run a deficit every year, borrowed to pay current expenses, and then borrowed more to service previous debt until the lenders belatedly ceased lending and the music stopped. Its debt and its real gross domestic product definitively parted company in 2001 and have grown continuously further apart, as shown Graph 1.

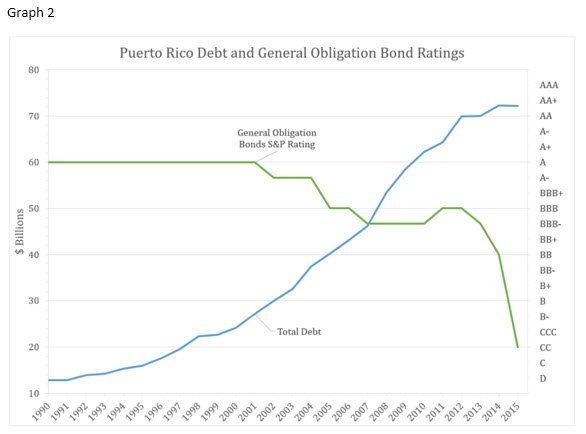

As its debt skyrocketed, the credit ratings of its bonds fell and then crashed. See Graph 2.

Where do we go from here? Addressing the deep, complicated, and contentious problems requires three steps:

The creation of an emergency financial control board to assume oversight and control of the financial operations of the government of Puerto Rico, which has displayed incompetence in fiscal management (or mismanagement), is a central aspect of the solution. This control board can be modeled on those successfully employed to address the insolvencies and financial mismanagement in the District of Columbia in the 1990s, in New York City in the 1970s and in numerous other places. More recently, the City of Detroit got an emergency manager along the same lines.

Such a board would be and must be quite powerful. The sine qua non for financial reform is to establish independent, credible authority over all books and records; to determine the true extent of the insolvency of the many indebted government entities—in particular to get on top of the real condition of the Government Development Bank; and to develop fiscal, accounting, control and structural reforms which will lead to future balanced budgets and control of the level of debt.

Needed reforms cited by Puerto Rican economist Sergio Marxuach in congressional testimony include:

[I]ncrease tax revenues by improving enforcement efforts, closing down ineffective tax loopholes, and modernizing its property tax system; crackdown on government corruption; significantly improve its Byzantine and unduly opaque financial reporting; reform an unnecessarily complicated permitting and licensing system that stifles innovation; … lower energy and other costs of doing business.

That’s a good list of projects.

Does all this take power and responsibility away from the Puerto Rican government? Of course it does – it needs to and it can be done. Under the Constitution, Congress has complete jurisdiction over territories like Puerto Rico. Just as in Washington and New York City, when the problems are straightened out, financial management will revert to the normal local government.

Pollock’s Law of Finance states that “Loans which cannot be repaid, will not be repaid.” Naturally, this law applies to the $115 billion owed by the Puerto Rican government, which is on its way to some form of restructuring and reorganization of debts. It seems clear that this should be done in a controlled, orderly and equitable process, which takes into account the various levels of seniority and standing among the many different classes of creditors.

The pending House bill puts the proposed oversight board in the middle of the analysis and negotiations of competing claims. If the reorganization cannot be voluntarily agreed upon, the process can move to the federal court, where the plan of reorganization would come from the oversight board.

Three objections have been made to this approach. One that has been advertised heavily claims that it is a “bailout.” Since no taxpayer money is planned to go to creditors, this is simply wrong and ridiculous. Bondholders taking losses is the opposite of a bailout.

A second is that bondholders may be disadvantaged versus pension claims, and this may affect the whole municipal bond market. Indeed, in the Detroit bankruptcy, the general obligation bonds got 74 cents on the dollar, while the general city employee pensions got 82 cents— an important haircut, but a smaller one. The political force of pension claims in insolvencies is a credit fact that all investors must take into account. If the national municipal bond market internalizes and prices the risks of unfunded pensions, thereby bringing more discipline on the borrowers, that seems like progress to me.

A third objection is that the bill’s approach would set a precedent for financially struggling states like Illinois, which they might follow. In my judgment, there is zero probability that Illinois or any other state would volunteer to have a financial control board imposed on it. Even leaving aside the fact that Puerto Rico is not a state, this argument is vacuous.

Of fundamental importance is that in the medium term, Puerto Rico must develop a sustainable economy—that is, a market economy to replace its historically government-centric one. Various ideas have been proposed relevant to this essential goal, and much more work is required. This is the most challenging of all the elements of the problem. Steps 1 and 2 must be done first, but Step 3 must be achieved for ongoing success.

One thoughtful investor in municipal bonds, reflecting on Puerto Rico, Illinois and other troubled political entities, concluded, “We don’t trust governments.” That made me think of how there have been more than 180 defaults and restructurings of sovereign debt in the last 100 years and how, further back, a number of American states defaulted on their debts and even repudiated them. So I wrote him, “I think that’s wise.”

Nonetheless, the immediate requirement to deal with the Puerto Rican debt crisis is government action.

Risk doesn’t stand still

Published in Library Of Law And Liberty.

Foolproof: Why Safety Can Be Dangerous and How Danger Makes Us Safe explores the movement and transformation of risks in adapting, self-referencing systems, of which financial systems are a notable example. In this provocative new book, the Wall Street Journal’s chief economics commentator Greg Ip contemplates how actions to reduce and control risk are often discovered to have increased it in some other way, and thus, “how safety can be dangerous.”

This is an eclectic exploration of the theme, ranging over financial markets, forest fires, airline and automobile safety, bacterial adaptation to antibiotics, flood control, monetary policy and financial regulation. In every area, Ip shows the limits of human minds trying to anticipate the long-term consequences of decisions whose effects are entangled in complex systems.

In the early 2000s, the central bankers of the world congratulated themselves on their insight and talent for having achieved, as they thought, the Great Moderation. It turned out they didn’t know what they had really been doing, which was to preside over the Great Leveraging. Consequently, and much to their surprise, they found themselves in the Great Collapse of 2007 to 2009, and then, with no respite, in the European debt crisis of 2010 to 2012.

Ip begins his book two decades before that, in 1989, at a high-level conference on the topic of financial crises. (Personally I have been going to conferences on financial crises for 30 years.) He cites Hyman Minsky, who “for decades had flogged an iconoclastic theory of business cycles that fellow scholars had largely ignored.” Minsky’s theory is often summarized as “Stability creates instability”—that is, periods of safety induce the complacency and the mistakes that lead to the crisis. He was right, of course. Minsky (who was a good friend of mine) added something else essential: the rise of financial instability is endogenous, arising from within the financial system, not from some outside “shock.”

At the same conference, the famous former Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker raised “the disturbing question” of whether governments and central banks “end up reinforcing the behavior patterns that aggravate the risk.” Foolproof shows that the answer is yes, they do.

Besides financial implosions, Ip reflects on a number of natural and engineering disasters, including flooding rivers, hurricane damage, nuclear reactor meltdowns, and forest fires, and concludes that in all of these situations, as well, measures were taken that made people feel safe, “and the feeling of safety allowed danger to re-emerge, often hidden from view.”

The natural and the man-made, the “forests, bacteria and economies” are all “irrepressibly adaptable,” he writes. “Every step we take to suppress the risks . . . will provoke some other, offsetting step.” So “neither the economy nor the natural world turned out to be as amenable to human management” as was believed.

As Velleius Paterculus observed in the history of Rome that he wrote circa 30 AD, “The most common beginning of disaster was a sense of security.”

Why are we like this? Ip demonstrates, for one thing, how quickly memories fade as new and unscarred generations arrive to create their own disasters. Nor is he himself immune to this trait, writing: “The years from 1982 to 2007 were uncommonly tranquil.”

Well, no.

In fact, the years between 1982 and 1992 brought one financial disaster after another. In that time more than 2,800 U.S. financial institutions failed, or on average more than 250 a year. It was a decade that saw a sovereign debt crisis; an oil bubble implosion; a farm credit crisis; the collapse of the savings and loan industry; the insolvency of the government deposit insurer of the savings and loans; and, to top it off, a huge commercial real estate bust. Not exactly “tranquil.” (As I wrote last year, “Don’t Forget the 1980s.”)

“Make the most of memory,” Ip advises. After the Exxon Valdez oil spill disaster, he says, the oil company “used the disaster to institute a culture of safety . . . designed to maintain the culture of safety and risk management even as memories of Valdez fade.”