Tags

Financial Systemic Issues: Booms and Busts - Central Banking and Money - Corporate Governance - Cryptocurrencies - Government and Bureaucracy - Inflation - Long-term Economics - Risk and Uncertainty - Retirement Finance

Financial Markets: Banking - Banking Politics - Housing Finance - Municipal Finance - Sovereign Debt - Student Loans

Categories

Blogs - Books - Op-eds - Letters to the editor - Policy papers and research - Testimony to Congress - Podcasts - Event videos - Media quotes - Poetry

Puerto Rico: Time for Congress to act

Published by the R Street Institute.

The finances of Puerto Rico’s government are unraveling rapidly. With the commonwealth government broke and scrambling, its Legislative Assembly already has empowered Gov. Alejandro García Padilla to declare a moratorium on all debt payments.

In a report that was kept secret, the Government Development Bank, which is at the center of complex intragovernmental finances, was found last year to be insolvent. Adding together the explicit government debt and the liabilities of its 95 percent unfunded government pension plan, the total problem adds up to about $115 billion.

There is no pleasant outcome possible here. The first alternative available is to deal with many hard decisions and many necessary reforms in a controlled fashion. The second is to have an uncontrolled crisis of cascading defaults in a territory of the United States.

Congress needs to choose the controlled outcome by creating a strong emergency financial control board for Puerto Rico—and to do it now. This is the oversight board provided for in the bill currently before the House Natural Resources Committee. The bill further defines a process to restructure the Puerto Rican government’s massive debts, which undoubtedly will be required.

Some opponents of the bill, in a blatant misrepresentation, have been calling it a “bailout” to generate popular opposition. To paraphrase Patrick Henry, these people may cry: Bailout! Bailout!…but there is no bailout.

Enacting this bill is the first step to get under control a vast financial mess, the result of many years of overborrowing, overlending and financial and fiscal mismanagement.

Again to cite Patrick Henry, “Why stand we here idle?”

Puerto Rico bill proceeds with oversight board and no bailout

Published by the R Street Institute.

The House Natural Resources Committee is taking testimony today on its bill to address the Puerto Rico debt crisis, and could send a finished bill to the full U.S. House as early as tomorrow. As the Puerto Rican government’s finances continue to unravel rapidly, it is decidedly time for Congress to act.

The bill gets two fundamental issues right. It takes the essential first step: creating a strong emergency financial control board to oversee and reform the Puerto Rican government’s abject financial situation and operations. The oversight board the bill provides should be put in place as soon as possible. (See “Puerto Rico needs a financial control board.”)

Second, it provides no bailout for the bondholders. Should U.S. taxpayers provide a bailout to those who unwisely lent money to the Puerto Rican government? Clearly not. When governments spend and borrow themselves into insolvency, those who provide the debt should bear the risk on their own. Since the citizens of Puerto Rico themselves pay no federal income taxes, this imperative is even stronger.

Objections are raised that these losing investments were made while relying on the Puerto Rican government’s inability to enter bankruptcy proceedings. But the fact that you cannot enter bankruptcy does not stop you from going broke. When you are broke, and the cash is gone, and the lenders won’t lend to you any more, the question becomes how big a loss the various parties will take. Nobody knows the right answer at this point: that’s one of the reasons we need the oversight board.

The Puerto Rican government has now made settlement offers for outstanding debt which would pay, on average, about 66 cents to 75 cents on the dollar. For the debt held by its own residents, it offers a special deal: you could be paid at par, starting 49 years from now, and get an interest rate of 2 percent. Discounted at 5 percent, this implies a value of about 45 cents on the dollar. Presumably, this would be a way to avoid recognizing losses for Puerto Rican credit unions which would not mark to market.

There are three contenders for the vanishing cash of the Puerto Rican government: the creditors, the ongoing operations of the government and the beneficiaries of the large and virtually unfunded government pension plan. How to share the losses among the claimants is the fight at the center of all insolvencies and will be so in this one, too.

There is no pleasant way out of the current situation. We won’t even know how deep the component insolvencies are until the oversight board gets in there and figures it out. In the meantime, we also should wrestle with the third fundamental issue: how to create a successful market economy to replace Puerto Rico’s current failed government-centric one.

Update on U.S. property prices in the Fed’s brave new world

The attached policy short was published in the Spring 2016 edition of Housing Finance International, the quarterly journal of the International Union for Housing Finance.

Readers of my last update in Housing Finance International may recall this principle: The collateral for a home mortgage loan is not the house, but the price of the house. Likewise, the collateral for a commercial real estate loan is not the property, but the price of the property.

A key question always accompanies this principle: How much can asset prices change? The answer is always: More than you think. Prices can go up more than you expected, and they can go down a lot more than you thought possible; a lot more than your “worst case scenario” projected. The more prices have gone up in the boom, and the more leverage has been induced by their rise, the more likely are their subsequent fall and the bust.

From this, we can see how dangerous a game the Federal Reserve and other major central banks have played by promoting asset price inflation through their monetary manipulations of the last several years. Unavoidably, among the asset prices affected are those of residential and commercial real estate.

The Fed has tried asset price inflation before. In the wake of the collapse of the tech stock bubble in 2000, under then-Chairman Alan Greenspan, the Fed set out to promote a housing boom in order to create a “wealth effect” that would offset the recessionary effects of the previous bubble’s excesses. I call this the Greenspan Gamble. As we know, the boom got away into a new and far more damaging bubble. It was in fact a simultaneous double bubble in housing and in commercial properties. This is made apparent in Graph 1, showing the decade from 2000-2010. These events stripped Greenspan of his former masterful aura and of his former media title, “The Maestro.”

The economically sluggish aftermath of the twin bubbles brought us, under Greenspan’s successor, Ben Bernanke, the Bernanke Gamble. The Fed once again set about promoting asset price inflation and “wealth effects” to offset the financial and economic drag of the previous excesses. The brave new world of the Bernanke Gamble includes exceptionally low interest rates, years of negative real short-term interest rates, and the effective expropriation of savers, while making the Fed into the biggest investor in mortgage assets in the world. Of course this has inflated real estate prices.

Graph 2 shows U.S national average house prices from 1987 to 2015 and their trend line. The bubble’s extreme departure from the trend is obvious. It is essential to observe that the six years of price deflation, from the peak in 2006 to 2012, while a 27 percent aggregate fall, brought house prices only back to their trend line – there was very little downside overshoot. Since 2012, prices have risen by 31 percent in less than four years, and are now 12 percent over their trend line. This rate of increase is unsustainable. On top of that, the U.S. government is once again, as it did the last time around, pushing mortgage loans with small down payments and greater credit risk. Some politicians have apparently learned nothing and forgotten everything.

The price behavior of commercial real estate has been even more extreme. As shown in Graph 3, while commercial real estate prices peaked in 2008 at a level similar to that of housing in 2006, their fall was much steeper, dropping 40 percent, or about half again as much as house prices. The difference presumably reflects the large government efforts to prop up the prices of houses.

From the 2010 bottom in commercial real estate prices, they have now almost doubled, and the current index is 17 percent above the prices at the peak of the bubble. Cranes are busy, and this so far makes the Fed happy, since it means strong construction spending. But what comes next?

Asset prices need to be understood on an inflation-adjusted basis. Over long periods of time, the inflation-adjusted increase in U.S. house prices is very modest – only about 0.6 percent per year, on average. This means home ownership is a good long-term hedge against the central bank’s endemic inflation, but on average, not a great investment. Graph 4 shows real house price movements over 40 years, from 1975 to 2015, stated in constant 2000 dollars, and the modestly increasing long-term trend line. As of the end of 2015, average house prices are 19 percent above the inflation-adjusted trend – not yet a bubble, but distinctly a renewed boom.

Rapid increases in house and commercial real estate prices is what in the past has induced extrapolations of further price increases, looser credit standards, increasing leverage, and overconfidence among lenders and borrowers. We can only hope that this time they remember that it is the price, not the property, which is being leveraged.

Will the Bernanke Gamble end in similar fashion to the Greenspan Gamble? Will the historical average of a financial crisis about every 10 years continue? We will find out.

On Puerto Rico, Congress is moving in the right direction

Published by the R Street Institute.

The draft bill to address Puerto Rico’s debt crisis – released late last week by House Natural Resources Committee Chairman Rob Bishop, R-Utah – marks a step in exactly the right direction. It realistically faces the fact that the government of Puerto Rico has been unable to manage its own finances, has constantly borrowed to finance its deficits and is now broke.

What is to be done as the Puerto Rican government displays its inability to cope with its debt burden — which, adding together its explicit debt plus its 95 percent unfunded pension liabilities, totals about $115 billion?

As the draft bill provides, the first required step is very clear: Congress must create a strong emergency financial-control board (“oversight board” is the draft’s term) to assume oversight and control of the commonwealth’s financial operations. This is just as Congress did successfully with the insolvent District of Columbia in 1995; what New York State, with federal encouragement, did with the insolvent New York City in 1975; and what the State of Michigan did with the appointment of an emergency manager for the insolvent City of Detroit in 2013. Such actions have also been taken with numerous other troubled municipal debtors. They are hardly an untried idea.

This should be the first step. As the bill provides, other steps will need to follow. To begin, the oversight board will need to establish independent authority over books and records, publish credible financial statements, and determine the extent of the insolvency of the various parts in the complex tangle of Puerto Rican government borrowing entities—especially of the Government Development Bank, which lends to the others. Then it will have to help develop fiscal, accounting, tax-collection and structural reforms that lead to future fiscal balance.

The oversight board will have to consider and report to Congress on the best ways to deal with the current excessive and unpayable debt, including pension liabilities. The draft bill provides a key role for the board in debt restructuring issues.

Puerto Rico has a failing, government-centered, dependency-generating political economy. The draft bill envisions the oversight board assisting with economic revitalization, which will be a key consideration going forward.

Needless to say, the current government of Puerto Rico does not like the idea of having its power and authority reduced. But this always happens to those who fail financially. The people of Puerto Rico understand this: 71 percent in a recent University of Turabo poll favored “a fiscal control board…that has broad powers.” In time, revitalized finances will lead to a more successful local government.

The draft bill is headed for introduction and hearings. Stay tuned.

Sizing up the FCIC report five years later

Published by the R Street Institute.

Ongoing debates about the financial crisis of 2007 to 2009 keep reminding us that economics is not a science. It can’t be used by governments to manage economic and financial affairs to some preordained outcome. Not only is it rather poor at predicting the future, but its practitioners often are unable to agree even on how to interpret the past.

Nonetheless, accepted economic stories or myths do get established in the media and political mind. One example from a different crisis is that Herbert Hoover was a donothing president in the face of the developing depression. In fact, he was an energetic and ardent interventionist. The real question is whether his many interventions were good or bad.

What are the myths of our more recent crisis?

When it comes to the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission, created by Congress in May 2009 to study the causes of the crisis, we must remember that the “report” the 10-member commission finally delivered in January 20112 was actually three separate reports:

The majority report, voted for by the six Democratic-appointed commissioners and no Republican-appointed commissioners, essentially concluded the primary cause was insufficient government intervention.

A minority dissent of three of the Republican-appointed commissioners concluded the causes of the crisis were many and interacting, with plenty of blame to go around.

A separate dissent by Peter Wallison argued in detail that the biggest problem was too much government intervention, resulting in extreme distortions in housing-finance market.

In the five years since these reports, what more have we learned? From this distance, can we put the FCIC’s majority and dissenting reports, and the crisis itself, into a convincing overall perspective?

The R Street Institute convened panel of experts, including two former FCIC members, for a Feb. 4, 2016 conference on these issues. The gathering served to provide an informed, insightful and provocative discussion. We are pleased to present this summary of their presentations.

The temptations of housing finance bubbles

A version of this policy short originally appeared in the Winter 2015 issue of the journal Housing Finance International.

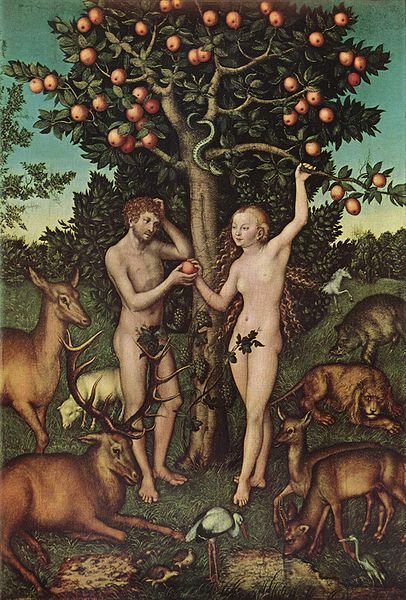

Running up the leverage is the snake in the housing finance Garden of Eden. It is a constant set of alluring temptations to enjoy the fruit of increased risk in the medium term, while setting ourselves up for the inevitable fall.

Let us view this famous painting by Lucas Cranach:

The woman is Fannie Mae. The man is Freddie Mac. The snake is whispering, “If you just run up the leverage of the whole housing finance system, you will become powerful and rich.” Fannie and Freddie are about to eat the apple of risk, which will indeed make them very powerful and very rich for a while, after which they will be shamed, humiliated and punished.

Bubbles in housing finance have occurred in many countries and times. They always end painfully, yet they keep happening. As the prophet said (slightly amended), “There is nothing new under the financial sun. The cycle that hath been, it is that which shall be.” Why is this?

Consider this quotation: “The [banking] failures for the current year have been numerous…In many cases, however, the unfavorable conditions were greatly aggravated by the collapse of unwise speculation in real estate.” What year was that? It could have been 2008, to be sure, but it is actually from 1891, as the then-U.S. comptroller of the currency looked sadly at the wreck of many of the banks of his day.

Some people say the problem is that housing lenders who go broke need to be personally punished, to get their incentives right. Economists are big, not without reason, on worrying about economic incentives. But a bigger problem is that it is so hard to know the future. Housing lenders don’t create housing-finance collapses on purpose, but by mistake.

The city of Barcelona in the 14th century decided to manage the incentives of bankers by decreeing that those who defaulted on their deposits would be subject to capital punishment. And as one financial history tells us, “at least one banker, Francesch Castello, was beheaded directly in front of his counter in 1360.” But this did not stop banks from failing.

One of the most important reasons that housing-finance bubbles are so hard to control is that they make nearly everyone happy while they last. Who is making money from a housing-finance bubble? Almost everybody. This is why the experience of a bubble is so insidious.

For example, take the most recent American experience. For a long time, the seven years of 2000-2006, the housing-finance bubble generated profits and wealth. A lot of the profits and wealth turned out to be illusory in the end, but at the time, some of it was real and all of it seemed real. As house prices rose, borrowers made more money if they bought more expensive houses with the maximum amount of leverage. Property flippers bought and sold condominiums for quick and repetitive profits, even if no one was living in them. Housing lenders had big volumes and profits. Their officers and employees got big bonuses. Numerous officers of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac made more than $1 million a year each. Real estate brokers had high volumes and big commissions. Equity investors saw the value of their housing-related stocks go up. Fixed-income investors all over the world enjoyed the returns from subprime mortgage-backed securities, which seemed low risk, and from Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac securities, which seemed to be, and actually were, guaranteed by the U.S. government.

Most importantly, the 75 million households that were homeowners saw the market price of their houses keep rising. This felt like, and was discussed by economists as, increased wealth. Of course, this was politically popular. The new equity in their houses at then-market prices allowed many consumers to borrow on second mortgages and home-equity loans, so they could spend money they had not had to earn by working. Then-Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan smiled approvingly on this housing “wealth effect,” which was offsetting the recessionary effects of the collapse of the previous bubble in technology stocks in 2000.

Homebuilders profited by a boom in new building. Local governments got higher real-estate-transaction taxes and greater property taxes, which reflected the increased tax valuations of their citizens’ houses. They could increase their spending with the new tax receipts. The investment banks, which pooled mortgages, packaged them into ever more complex mortgage-backed securities, and sold and traded them, made a lot of money and paid big bonuses to the members of their mortgage operations, including the former physicists and mathematicians who built the models of how the securities were supposed to work. Bond-rating agencies were paid to rate the expanding volumes of mortgage-backed securities and were highly profitable. Bank regulators happily noted that bank capital ratios were good, and that zero banks failed in the United States in the years 2005 and 2006 – the very top of the bubble. In the next six years, 468 U.S. banks would fail.

The politicians are not to be forgotten. The politicians trumpeted and took credit for the increasing home ownership rate, which the housing finance bubble temporarily carried to 69 percent, before it fell back to its historical level of 64 percent. The politicians pushed for easier credit and more leverage for riskier borrowers, which they praised as “increasing access” to borrowing. (The snake had most certainly been whispering to the politicians, too.)

The bubble was highly profitable for everybody involved – as long as the house prices kept going up. As long as house prices rise, the more everybody borrows, the more money everybody makes. This general happiness creates a vast temptation to keep the leverage increasing at all levels.

This brings us to two essential questions.

The first is: What is the collateral for a mortgage loan?

Most people answer, “That’s easy – the house.” But that is not the correct answer.

The correct answer is: Not the house, but the price of the house. The only way a housing lender can recover from the property is by selling it at some price.

The second key question is: How much can a price change? To this question, the answer is: A lot more than you think. It can go up a lot more than you expected, and it can then go down a lot more than you thought possible. It can go down a lot more than your worst-case planning scenario dared to contemplate.

So the temptations of housing-finance bubbles generate mistaken beliefs about how much prices can go down. American housing experts knew that house prices could fall on a regional basis, but most were convinced that house prices would not fall on a national average basis. Of course, now we know they were wrong, and that national average house prices fell by 30 percent. And they fell for six years.

By then, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac had been banished from their pleasant housing finance Garden of Eden. Here they are, being sent into government conservatorship, as depicted by Michelangelo:

In conservatorship they remain to this day, more than seven years after their failure. Having played a key role in running up the leverage of the whole system, they had suffered a fall they never thought possible.