Tags

Financial Systemic Issues: Booms and Busts - Central Banking and Money - Corporate Governance - Cryptocurrencies - Government and Bureaucracy - Inflation - Long-term Economics - Risk and Uncertainty - Retirement Finance

Financial Markets: Banking - Banking Politics - Housing Finance - Municipal Finance - Sovereign Debt - Student Loans

Categories

Blogs - Books - Op-eds - Letters to the editor - Policy papers and research - Testimony to Congress - Podcasts - Event videos - Media quotes - Poetry

Slick accounting at the Federal Reserve could prove disastrous

Published in The Hill.

“Mr. Chairman, on exhibit two, panel four, ‘deferred asset.’ This is kind of a nice term, ‘deferred asset.’ As far as I know, the committee has never used the deferred asset. It strikes me as a possible political firefight to bring that into play. All of the scenarios here, other than option one, if I’m reading this correctly, would bring the deferred asset into play, with possible repercussions, I think, for the Federal Reserve.”

This was James Bullard, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, speaking at the September 2012 meeting of the Federal Open Market Committee, according to the minutes. Said a staff member in reply, “It has never been the case that we have had, for the Federal Reserve System as a whole, a deferred asset.” But they knew that they might have one going forward. Earlier in the meeting, the staff had reported that all the options considered to reduce the Fed’s bond portfolio would cause the “creation of a deferred asset,” perhaps even a “substantial deferred asset.”

What in the world were they talking about? In this context, what did this, as Bullard ironically said, “nice” term mean? In fact, they were discussing how, if they ever tried to reduce their huge portfolio of long-term Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities, they were liable to take big losses. They were pondering the effect which the losses arising from any attempt to normalize their balance sheet would have on their financial condition.

What the Fed meant by “deferred asset” in clear language is the “net losses we would take.” What would be deferred is the recognition of the losses in retained earnings. The losses under consideration might occur by selling some of the Fed’s vast investment in long-term securities for less than it paid for them. Could this happen? Of course. Buy at the top for $100 and sell later for $95 means a loss of $5 for anybody.

Already in 2012, the Federal Open Market Committee was struggling with the clear possibility that such losses could be very large, indeed much larger than the Fed’s net worth. Thus, such losses had the potential to render the central bank insolvent on a balance sheet basis, as well as making it it so that the Fed would be sending no money to the Treasury to reduce the budget deficit, perhaps for several years.

In one scenario presented to the Federal Open Market Committee at that 2012 meeting, the “deferred asset” would get to about $175 billion. At the time of the meeting, the Fed’s net worth was only $55 billion, so its leaders were contemplating the possibility of losing up to three times its capital. This was happening while running a long-term securities portfolio of $2.6 trillion.

If negative net worth did arrive, the Fed could still print any money needed to pay its bills, but the balance sheet wouldn’t look so good. And might not publishing a balance sheet with negative net worth mean a “possible political firefight” in Bullard’s phrase? What might Congress say or do? The Fed didn’t want to find out. So it invented having a “deferred asset,” if necessary, rather than reporting a negative net worth.

In short, this “deferred asset” would be an imaginary asset. It would be booked in this fashion to avoid recognizing the effect of net losses on capital. In accounting terms, it would be a big debit looking for someplace to go. The proper destination of the debit for everybody in the world, including the Fed, is to retained earnings, where it would reduce capital, or even make it negative. But the Fed does not choose to allow this, and the central bank defines its own accounting rules.

So the Fed would send the debit to an accounting “deferred asset” instead, which hides the loss and overstates capital. Harshly described, for ordinary banks, this would be called accounting fraud. So more than five years ago, the Fed understood very well the big losses that might result from its massive “quantitative easing” investments, and how such losses might dwarf the Fed’s capital. It knew it could prevent showing a negative net worth by a slick accounting move. Hence the extensive discussion of the “deferred asset,” which does indeed sound a lot better in the minutes than “negative capital.”

Since then, the Fed’s portfolio is much bigger, up to $4.2 trillion, so the potential losses are much bigger now, while the Fed’s capital is much smaller, down to $39 billion because the Congress expropriated a lot of its retained earnings. Interest rates have gone up. Selling down the Fed’s portfolio could now cause an even bigger negative net worth, or “deferred asset.” As we know, the Fed has concluded not to make any sales, only move extremely slowly toward balance sheet normalization by holding all its long-term portfolio to maturity.

Should the Federal Reserve, in the circumstances of 2012 or now, reveal the projected losses from any portfolio sales and resulting “deferred asset” to the public? Should it discuss candidly with its boss, the Congress, how big the losses and negative net worth might turn out to be? Or should it just prepare the accounting gimmick for use, if necessary, worry in private, put on a good face in public, and hope for the best? What would you do, thoughtful reader, in their place?

Federal Reserve will be judged by future on these years of low rates

Published in The Hill.

The government’s official interest rate price-fixing committee, otherwise known as the Federal Reserve, has just raised its target fed funds rate by a quarter-point. This surprised no one, as the Fed intended, since it works hard to manage expectations.

What would the rate be if it were set in private markets instead of by a government committee? No one knows, but presumably it would be higher.

The Fed’s latest move still leaves interest rates at remarkably low levels. In the 1980s and 1990s, most people would have considered it impossible for the fed funds rate to be under 2 percent. Now we have the Fed’s current target range of 1.5 to 1.75 percent—to make it easy, let’s just call it 1.75 percent. Not only is this rate low, but in real inflation-adjusted terms, it is negative. In February, the Consumer Price Index went up 2.2 percent year-over-year, so the new fed funds target in real terms is 1.75 percent minus 2.2 percent = negative 0.45 percent.

It looks like it will take one more increase, at least, to get the real fed funds rate up to around zero and numerous increases after that to approach a normal level. Needless to say, normal real interest rates are positive, not negative.

What might a normal level be? We can make a fair guess by looking at long-term averages. Graph 1 shows nominal fed funds rates and inflation rates from mid-1954 to year-end 2017.

Over this long term, the fed funds rate averaged 4.86 percent. The annual rate of inflation averaged 3.56 percent. So the long-term average real fed funds rate was 1.3 percent.

If inflation going forward runs at the Fed’s target inflation rate of 2 percent, it would suggest a normalized fed funds rate of 3.3 percent. To get there would take six more quarter-point increases. On similar logic, the normalized yield on the 10-year Treasury note would be 4.5 percent, instead of the current 2.8 percent, and the rate on a 30-year mortgage loan would be 6.2 percent, up from the current 4.4 percent level. Of course, if inflation turns out to move higher than 2 percent, the normalized fed funds rate, and also the other rates, will be correspondingly higher.

Graph 2 shows the real fed funds rates over the same years.

As is apparent from this graph, we have lived through and remain in an exceptionally long period of negative real fed funds rates. It is by far the longest stretch of such negative real rates in our six decades of data. While normal real fed funds rates are positive, it is not unusual for them to be negative for some periods, such as when the Fed is facing a recession, or a financial crisis, or both, or has a desire to inflate asset prices. Extended negative real interest rates are good at inducing asset-price booms.

Since the 1950s, there were negative real fed funds rates during the following times:

Six quarters during 1956-1958;

Two quarters during 1970-1971;

15 quarters during 1974-1977;

Five quarters during 1979-1980;

Three quarters at about zero in 1992-1993;

11 quarters during 2002-2005;

Three quarters in 2008.

And then the all-time champion run of negative real fed funds rates:

30 quarters, equivalent to 7.5 years, during 2009 to now.

It is hardly surprising that this period has been accompanied by booms in equity, bond and house prices. Was the Fed’s strategy during these years wise? The future will judge that, looking back.

For now, we can say, in sum, that the Fed’s target fed funds rate remains remarkably low, is still negative in real terms, and has a long way to go to get back to normal.

Economic crises are invariably failures of the imagination

Published in Real Clear Markets.

A fundamental issue in all risk management is oversight vs. seeing. You can be doing plenty of oversight, analysis, regulation and compliance, with much diligence and having checkers check on checkers, but is the whole process able to envision the deep and surprising risks that are the true fault lines under your feet? Or are you only analyzing, regulating, writing up and color coding dozens of factors which while important, are not the big risk which is going to take you and perhaps the system of which you are a part, down? For example, in the midst of your risk management oversight efforts, whether as a company or as the government, could you see in 2005 or 2006, or at the latest by 2007, that U.S. average house prices across the whole country, were likely to drop like a stone? And see what would happen then?

Most people, including the most intelligent, experienced and informed, could not.

Former Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner, in his memoir of the 2007-2009 financial crisis, Stress Test (2014), draws this essential conclusion: “Our crisis, after all, was largely a failure of imagination. Every crisis is.” If you can’t imagine it, if you consider that the deep risk event is unimaginable or impossible, your oversight will not see the risk. “For all our concern about ‘froth’,” Geithner continues, “we didn’t foresee how a nationwide decline in home prices could induce panic in the financial system.”

This is a profoundly important insight. Geithner expands on it: “Our failures of foresight were primarily failures of imagination, like the failure to foresee terrorists flying planes into buildings before September 11. But severe financial crises had happened for centuries in multiple countries, in many shapes and forms, always with pretty bad outcomes. For all my talk about tail risk, negative extremes, and stress scenarios, our visions of darkness still weren’t dark enough.”

That was not for lack of effort, but for lack of seeing. “The actual main failing was over-reliance on formal econometric models,” banking scholar Charles Goodhart suggests in his acute essay, “Central bank evolution: lessons learnt from the sub-prime crisis” (2016). He points out that as the housing bubble was inflating, there was copious housing finance data which could be and was analyzed:

“There were excellent monthly data on virtually all aspects of mortgage finance in the USA starting from the 1950s. By the 2000s such data provided over 50 years of all aspects of US mortgage finance. During this period, there had only been a very few months in which the value of houses, and the mortgages related to them, of a regionally diversified portfolio of housing assets over the US as a whole had faced a loss, and then only a very small one.

“While there had been sharp declines in housing valuations in certain specific regions, i.e. the North East in 1991-2, the oil producing states in the mid-1980s, etc., a regionally diversified portfolio virtually never showed a loss, and then only a minor one, over these 50 years.” The conclusion seemed clear enough at the time: house prices did not, so would not, fall on a national average basis. A portfolio of mortgages diversified across regions would be protected. “Virtually everyone was sucked into the general conventional wisdom that housing prices”—on average—“were almost sure to continue trending generally upwards.”

This clear, though in retrospect completely wrong, conclusion could be professionally quantified: “Put those data into a regression analysis, and then what you will get out is an estimate that any loss of value in a regionally diversified portfolio of greater than about three or four percent would be…highly improbable.” But as the bubble got maximally inflated, its shriveling became highly probable instead of improbable. As we know, average U.S, house prices went down by 27% and fell not for a few months, but for six years, in spite of all kinds of government interventions. The housing market went down for longer than a great many people could stay solvent.

“Of course,” Goodhart reminds us, “econometric regressions are based on the implicit assumption that the future will be like the past.” The less of the past we know, the worse an assumption this is. In this case, fifty years and one country, even a very big country, were not enough.

To expand how much of the past we have studied, both in terms of more time and more places, is perhaps one way to improve our ability to see risks, imagine otherwise unimaginable outcomes, and thus improve our risk oversight. Perhaps. There are no guarantees of success.

House prices: What the Fed hath wrought

Published in The Hill.

After the peak of the housing bubble in 2006, U.S. house prices fell for six years, until 2012. Are these memories getting a little hazy?

The Federal Reserve, through forcing years of negative real short-term interest rates, suppressing long-term rates, and financing Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to the tune of $1.8 trillion on its own vastly expanded balance sheet, set out to make house prices go back up. It succeeded. Indeed it has overachieved. Average house prices are now significantly higher than they were at the top of the bubble. This is shown in the following 20-year history of the familiar S&P Case-Shiller national house price index.

Read the full article here.

Banks need more skin in the housing finance game

Published by American Banker.

We all know it was a really bad idea in the last cycle to concentrate so much of the credit risk of the huge American mortgage loan market on the banks of the Potomac River — in Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.

But the concentration is still there, a decade later.

The Fannie and Freddie-centric U.S. housing finance system removes credit risk from the original lenders, taking away their credit skin in the game. It puts the risk instead on the government and the taxpayers.

Many realized in the wake of the crisis that this was a big mistake (although a mistake made by a lot of smart people) in the basic design of the inherently risk-creating activity of lending money. Many realized after the fact that the American housing finance system needed more credit skin in the game.

Skin-in-the-game requirements were legislated for private mortgage securitizations by the Dodd-Frank Act, but do not apply to lenders putting risk into Fannie and Freddie. Regulatory pressure subsequently caused Fannie and Freddie to transfer some of their acquired credit risk to investors — but this is yet another step farther away from those who originated the risk in the first place.

That isn’t where the skin in the game is best placed. The best place, which provides the maximum alignment of incentives, and the maximum use of direct knowledge of the borrowing customer, is for the creator of the mortgage loan to retain significant credit risk. No one else is as well placed.

The single most important reform of American housing finance would be to encourage more retention of credit skin in the game by those making the original credit decision.

In this country, we unfortunately cannot achieve the excellent structure of the Danish mortgage bond system, where 100% of the credit risk is retained by the lenders, and 100 percent of the interest rate risk is passed on to the bond market. The Danish mortgage bank which makes the loan stays on the hook for the default risk and receives corresponding fee income. The loans are pooled into mortgage bonds, which convey all the interest rate and prepayment risk to bond investors. This system has been working well for over 200 years.

There are clearly many American mortgage banks which do not have the capital to keep credit skin in the game in the Danish fashion. But there are thousands of American banks, savings banks and credit unions which do have the capital and can use to it back up their credit judgments. The mix of the housing finance system could definitely be shifted in this direction.

If you are a bank, your fundamental skill and your reason for being in business is credit judgment and the managing of credit risk. Residential mortgage loans are essential to your customers and are the biggest loan market in the country (and the world). Why do you want to divest the credit risk of the loans you have made to your own customers, and pay a big fee to do so, instead of managing the credit yourself for a profit? There is no good answer to this question, unless you think your own mortgage loans are of poor credit quality. For any bankers who may be reading this: Do you think that?

But, it will be objected: The regulators force me to sell my fixed-rate mortgage loans because of the interest rate risk, which results from funding 30-year fixed-rate loans with short-term deposits. True, but as in Denmark, the interest rate risk can be divested while credit risk is maintained. For example, the original 1970 congressional charter of Freddie provided lenders the option of selling Freddie high loan-to-value ratio loans by maintaining a 10% participation in the loan or by effectively guaranteeing them, not only by getting somebody else to insure them.

Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin recently told Congress that private capital must be put in front of any government guarantee of mortgages. That’s absolutely right — but whose capital? The best solution would be to include the capital of the lenders themselves.

In sharp contrast to American mortgage-backed securities in this respect are their international competitors, covered bonds. These are bonds banks can issue, collateralized by a “cover pool” of mortgage loans which remain assets of the bank. Thus covered bonds allow a long-term bond market financing, but all the credit risk stays on the bank’s balance sheet, with its capital fully at risk.

American regulators and bankers need to shake off their assumption, conditioned by years of Fannie and Freddie’s government-promoted dominance, that the “natural” state of things is for mortgage lenders to divest the credit risk of their own customers. The true natural state for banks is the opposite: to be in the business of credit risk. What could be more obvious than that?

The housing finance system should promote, not discourage, mortgage lenders staying in the credit business. Regulators, legislators, accountants and financial actors should undertake to reform regulatory, accounting and legal obstacles to the right alignment of incentives and risks. The Federal Housing Finance Agency should be pushing Fannie and Freddie to structure their deals to encourage originator retention of credit risk.

The result will be to correct, at least in part, a fundamental misalignment that the Fannie and Freddie model foisted on American housing finance.

Confiscation of gold by the federal government: A lesson

Published in Real Clear Markets.

Historically as well as now, people in America tried to protect themselves against the government’s devaluation of their dollars by holding gold; and formerly, by buying Treasury bonds which promised to pay in gold. The fundamental thought was and is the same that many holders of Bitcoin and other “cryptocurrencies” have now: hold something that the government cannot devalue the way it can its official currency.

Unfortunately for such an otherwise logical strategy, governments, even democratic governments, when pushing comes to shoving, may use force to control and even take away what you thought you had. The year 1933 and the new Franklin Roosevelt presidency provide vividly memorable, though little remembered, examples. First the U.S. Treasury defaulted on its promises to pay gold bonds in gold; then under notable executive orders, the U.S. government confiscated the gold of American citizens and threatened them with prison if they didn’t turn it in. It moreover prohibited the future holding of any gold by Americans, an outrageous prohibition which lasted four decades, until 1974.

All this may seem unimaginable to many people today, perhaps including Bitcoin enthusiasts, but in fact happened. Said Roosevelt in explanation, “The issuance and control of the medium of exchange which we call ‘money’ is a high prerogative of government.”

President Hoover had warned in 1932 that the U.S. was close to having to go off the gold standard. Running for President, Roosevelt called this “a libel on the credit of the United States.” He furthermore pronounced that “no responsible government would have sold to the country securities payable in gold if it knew that the promise—yes, the covenant—embodied in those securities was…dubious.” The next year, during Roosevelt’s own administration, this “covenant” was tossed overboard. Congress and the President “abrogated”—i.e. repudiated—the obligation of the government to pay as promised. One can argue that this was required by the desperate economic and financial times, but about the fact of the default there can be no argument.

Roosevelt’s Executive Order 6102, “Requiring Gold Coin, Gold Bullion and Gold Certificates to Be Delivered to the Government,” of April 5, 1933 marks an instructive moment in both American monetary and political history. To modern eyes, it looks autocratic, or perhaps could fairly be described as despotic.

The order begins, “By virtue of the authority vested in me by Section 5(b) of the Act of October 6, 1917,” without naming what act that is. Why not? Well, that was the Trading with the Enemy Act which was used to confiscate German property during the First World War.

The order states:

-“All persons are hereby required to deliver on or before May 1, 1933…all gold coin, gold bullion and gold certificates now owned by them or coming into their ownership.”

-“Until otherwise ordered any person becoming the owner of any gold coin, gold bullion or gold certificates shall, within three days after receipt thereof, deliver the same.”

-“The Federal Reserve Bank or member bank will pay therefore an equivalent amount of any other form of coin or currency”—in other words, we will give you some nice paper money in exchange.

Lastly, the threat:

-“Whoever willfully violates any provision of this Executive Order or of these regulations or of any rule, regulation or license issued hereunder may be fined not more than $10,000, or, if a natural person, may be imprisoned for not more than ten years, or both.”

Ten thousand 1933 dollars was a punitive fine—equivalent to about $190,000 today. But the real punishment for trying to protect your assets was “We’ll put you in jail for ten years!”

A few months later the order was revised and tightened up by Roosevelt’s Executive Order 6260, “On Hoarding and Exporting Gold” of August 28, 1933. It specifies that “no person shall hold in his possession or retain any interest, legal or equitable, in any gold,” and adds a reporting requirement: “Every person in possession of and every person owning gold…shall make under oath and file…a return to the Secretary of the Treasury containing true and complete information” about any gold holdings, “to be filed with the Collector of Internal Revenue.” So the IRS was brought in as an enforcer, too. The threat of fines and prison continued as before.

It’s a prudent idea to protect yourself against the government’s perpetual urge to depreciate its currency. But if pushing comes to shoving, how do you protect yourself against the government’s confiscating the assets you so prudently acquired—and its being willing to put you in prison if you try to keep them? What governments, even democratic ones, are willing to do when under sufficient pressure, is a lesson Bitcoin holders and everybody else can usefully consider.

Who is this ‘we’ that should manage the economy?

Published in Law & Liberty.

Adair Turner, the former Chairman of the British Financial Services Authority, has written a book about the risks and unpredictability of financial markets which has many provocative insights. It also has a frustrating blind spot about how government actions can and do contribute to financial crises.

Turner clearly addresses the failure of governments to understand what was going on as the crises of the 2000’s approached, including his notable mea culpa discussed below. But there is no discussion anywhere of the culpability of government actions which greatly contributed to inflating the bubble of housing debt and pumping up leverage on the road to the U.S. housing finance collapse.

The fateful history of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac is not discussed, even though Turner rightly emphasizes how dangerous leveraged real estate is as a key source of financial fragility. Fannie and Freddie, with $5 trillion in real estate risk, do not rate an entry in the index.

The problems of student debt make it into a footnote in chapter six, where its rapid growth in the United States is observed, along with the judgment that “much of it will prove unpayable,” but it is not mentioned that this is another government loan program.

The role of government deposit insurance in distorting credit markets, so notable in the U.S. savings and loan collapse of the 1980s, is not considered. That instructive collapse gets one passing sentence.

The Federal Reserve, along with other central banks, created the Great Inflation of the 1970s that led to the disastrous financial crises of the 1980’s. Seeking a house price boom and a “wealth effect” in the 2000’s, the Federal Reserve promoted what turned out to be a house price bubble. Turner provides no proposals about how to control the obvious dangers of central banks, although he does point out their mistake in thinking that they had created a so-called “Great Moderation.” That turned out to have been instead a Great Overleveraging.

There can be no doubt of Turner’s high intelligence, as his double first in history and economics at Cambridge and his stellar career, leading to his becoming Lord Turner, attest. But as an old banking boss of mine memorably observed, “it is easier to be brilliant than right.”

This universal principle applies as well to leading central bankers, regulators, and government officials of all kinds as it does to private actors. The bankers “that made big mistakes,” Turner correctly says, “did not consciously seek to take risks, get paid, and get out: they honestly but wrongly believed that they were serving their shareholders’ interests.” So also for the authors of mistaken government actions: they didn’t intend to make mistakes, but wrongly believed they were serving the public interest.

When former Congressman Barney Frank, for example, the “Frank” of the bureaucracy-loving Dodd-Frank Act, said before the crisis said that he wanted to “load the dice” with Fannie and Freddie, he never intended for the dice to come up snake eyes, but they did. Throughout the book, Turner displays the tendency to assume the consequences of government action to be knowable and benign, rather than unknowable and often perverse.

Debt and the Devil opens with the remarkable confession of government ignorance shown in the following excerpts. As he became Chairman of the Financial Services Authority in 2008, Turner relates:

“I had no idea we were on the verge of disaster.”

“Nor did almost everyone in the central banks, regulators, or finance ministries, nor in financial markets or major economics departments.”

“Neither official commentators nor financial markets anticipated how deep and long lasting would be the post-crisis recession.”

“Almost nobody foresaw that interest rates in major advanced countries would stay close to zero for at least 6 [now it’s 8] years.”

“Almost no one predicted that the Eurozone would suffer a severe crisis.” (That crisis featured defaults on government debt.)

“I held no official policy role before the crisis. But if I had, I would have made the same errors.”

If governments, their regulators, and their central banks cannot understand what is happening and the real risks are, then it is easy to see why their actions may be unsuccessful and indeed generate perverse results. So we have to amend some of Turner’s conclusions, to make his partial insights more complete.

“Central banks and regulators alone cannot make the financial system and economies stable,” he says. True, but we must add: but they can make financial systems and economies unstable by monetary and credit distortions.

We are “faced with a free market bias toward real estate lending” needs additionally: and an even bigger government bias and government promotion of real estate lending.

Turner quotes Charles Kindleberger approvingly: “The central question is whether central banks can contain the instability of credit and slow speculation.” This needs a matching observation: The central question is whether central banks can hype the instability of credit and accelerate speculation. They can.

“Banking systems left to themselves are bound to create too much of the wrong sort of debt” needs amendment: Banking systems pushed by governments to expand risky loans to favored political constituencies are bound to create too much of the wrong sort of debt, which will lead to large losses. This will be cheered by the government until it is condemned.

“At the core of financial instability in advanced economies lies the interaction between the potentially limitless supply of bank credit and the highly inelastic supply of real estate.” Insightful, but incomplete. Here is the complete thought: At the core of financial instability lies the interaction between the potentially limitless supply of the punchbowl of central bank credit, bank credit, government guarantees of real estate credit, and the inelastic supply of real estate.

“Private credit creation is inherently unstable.” Here the full thought needs to be: Private and government credit creation is inherently unstable. Indeed, Turner supplies a good example of the latter: Japanese government debt has become so large relative to the Japanese economy that it “will simply not be repaid in the normal sense of the word.”

According to Turner, what is to be done? He supplies a deus ex machina: “We.” So he asserts that “We need to manage the quantity and influence the allocation of credit,” and “We must influence the allocation of credit among alternate uses,” and “We must therefore deliberately manage and constrain lending against real estate assets.” Who is this “We”? Lord Turner and his friends? There is no “We” who know how credit should be allocated.

In an overall view, Turner concludes that “All complex systems are potentially unstable,” and that is true. But it must be understood that the complex system of finance includes inside itself all the governments, central banks, regulators and politicians, as well as all the private financial actors. Everybody is inside the system; nobody is outside the system, let alone above the system, looking down with ethereal perspective and the ability to manage everything. In particular, there is no “We” outside the complex system. “We,” whoever they may be, are inside the complex system with its inherent uncertainty and instability, along with everybody else.

Time to reform Fannie and Freddie is now

Published in American Banker.

The Treasury Department and the Federal Housing Finance Agency struck a deal last week amending how Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac’s profits are sent to Treasury as dividends on their senior preferred stock.

But no one pretends this is anything other than a patch on the surface of the Fannie and Freddie problem.

The government-sponsored enterprises will now be allowed to keep $3 billion of retained earnings each, instead of having their capital go to zero, as it would have done in 2018 under the former deal. That will mean $6 billion in equity for the two combined, against $5 trillion of assets — for a capital ratio of 0.1 percent. Their capital will continue to round to zero, instead of being precisely zero.

Here we are in the tenth year since Fannie and Freddie’s creditors were bailed out by Treasury. Recall the original deal: Treasury would get dividends at a 10 percent annual rate, plus — not to be forgotten — warrants to acquire 79.9 percent of both companies’ common stock for an exercise price of one-thousandth of one cent per share. In exchange, Treasury would effectively guarantee all of Fannie and Freddie’s obligations, existing and newly issued.

The reason for the structure of the bailout deal, including limiting the warrants to 79.9 percent ownership, was so the Treasury could keep asserting that the debt of Fannie and Freddie was not officially the debt of the United States, although de facto it was, is, and will continue to be.

Of course, in 2012 the government changed the deal, turning the 10 percent preferred dividend to a payment to the Treasury of essentially all Fannie and Freddie’s net profit instead. To compare that to the original deal, one must ask when the revised payments would become equivalent to Treasury’s receiving a full 10 percent yield, plus enough cash to retire all the senior preferred stock at par.

The answer is easily determined. Take all the cash flows between Fannie and Freddie and the Treasury, and calculate the Treasury’s internal rate of return on its investment. When the IRR reaches 10 percent, Fannie and Freddie have sent in cash economically equivalent to paying the 10 percent dividend plus retiring 100 percent of the principal.

This I call the “10 Percent Moment.”

Freddie reached its 10 percent Moment in the second quarter of 2017. With the $3 billion dividend Fannie was previously planning to pay on December 31, the Treasury’s IRR on Fannie would have reached 10.06 percent.

The new Treasury-FHFA deal will postpone Fannie’s 10 percent Moment a bit, but it will come. As it approaches, Treasury should exercise its warrants and become the actual owner of the shares to which it and the taxpayers are entitled. When added to that, Fannie reaches its 10 percent Moment, then payment in full of the original bailout deal will have been achieved, economically speaking.

That will make 2018 an opportune time for fundamental reform.

Any real reform must address two essential factors. First, Fannie and Freddie are and will continue to be absolutely dependent on the de facto guarantee of their obligations by the U.S. Treasury, thus the taxpayers. They could not function even for a minute without that. The guarantee needs to be fairly paid for, as nothing is more distortive than a free government guarantee. A good way to set the necessary fee would be to mirror what the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. would charge for deposit insurance of a huge bank with 0.1 percent capital and a 100 percent concentration in real estate risk. Treasury and Congress should ask the FDIC what this price would be.

Second, Fannie and Freddie have demonstrated their ability to put the entire financial system at risk. They are with no doubt whatsoever systemically important financial institutions. Indeed, if anyone at all is a SIFI, then it is the GSEs. If Fannie and Freddie are not SIFIs, then no one is a SIFI. They should be formally designated as such in the first quarter of 2018, by the Financial Stability Oversight Council —and that FSOC has not already so designated them is an egregious and arguably reckless failure.

When Fannie and Freddie are making a fair payment for their de facto government guarantee, have become formally designated and regulated as SIFIs, and have reached the 10 percent Moment, Treasury should agree that its senior preferred stock has been fully retired.

Then Fannie and Freddie would begin to accumulate additional retained earnings in a sound framework. Of course, 79.9 percent of those would belong to the Treasury as 79.9 percent owner of their common stock. Fannie and Freddie would still be woefully undercapitalized, but progress toward building the capital appropriate for a SIFI would begin. As capital increased, the fair price for the taxpayers’ guarantee would decrease.

The New Year provides the occasion for fundamental reform of the GSEs in a straightforward way.

FHFA’s g-fee calculation ignores the law

Published in American Banker.

In a recent report to Congress, the Federal Housing Finance Agency once again failed to satisfy a fundamental legal requirement. This is a requirement that the FHFA keeps ignoring, apparently perhaps because it doesn’t like it. But to state the obvious, the preferences of a regulatory agency do not excuse it from complying with the law.

The law requires that when the FHFA sets guarantee fees for Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, the fees must be high enough to cover not only the risk of credit losses, but also the cost of capital that private-sector banks would have to hold against the same risk. This is explicitly not the amount of capital that Fannie and Freddie or the FHFA might think would be right for themselves, but the cost of the capital requirement for regulated private banks.

This requirement, created by the Temporary Payroll Tax Cut Continuation Act of 2011, was clear and unambiguous. The law mandated a radical new approach to setting, increasing and analyzing Fannie and Freddie’s g-fees, based on a reference to the private market. In setting “the amount of the increase,” the law said, the FHFA director should consider what will “appropriately reflect the risk of loss, as well as the cost of capital allocated to similar assets held by other fully private regulated financial institutions.”

In other words, the director of the FHFA is instructed to calculate how much capital fully private regulated financial institutions have to hold against mortgage credit risk, the required return on that capital for such private banks and therefore the cost of capital for private banks engaging in the same risk as Fannie and Freddie. This includes the credit losses from taking this risk and operating costs, both of which must be added the private cost of capital. The net sum is the level of Fannie and Freddie’s guarantee fees that the FHFA is required to establish.

The law also further requires the FHFA to report to Congress on how Fannie and Freddie’s g-fees “met the requirements” of the statute – that is, how they included the cost of capital of regulated private banks.

However, if you read the FHFA’s October 2017 report on guarantee fees, nowhere in it will you find any discussion — not a single word — about private banks’ cost of capital for mortgage credit risk. There is the same amount of discussion — zero — about how that private cost of capital enters the analysis and calculation of Fannie and Freddie’s required g-fees. Yet this is the information and annual analysis that Congress demanded of the FHFA.

Why has the agency failed to fulfill its legal obligation?

A reasonable hypothesis is that the FHFA doesn’t like the answer that results when this analysis and calculation are performed, so it is tap-dancing instead of answering the question and implementing the answer. In short, the calculation required by the law results in much a higher level of g-fees than at present. This reflects the whole point of the statutory provision — to make the private sector competitive and to take away Fannie and Freddie’s subsidized cost of capital and the distortions it creates.

The FHFA certainly understands the importance of this issue. Its report clearly sets out the components of the calculation of g-fees, saying, “Of these components, the cost of holding capital is by far the most significant.” That would be the perfect section to add the required analysis of the cost of capital for regulated private financial institutions and to use that to calculate the legally required g-fees.

But instead, the report treats us to a discussion of how “each [government-sponsored enterprise] uses a proprietary model to estimate … the amount of capital it needs.” The mortgage companies use “models to estimate the amount of capital and … [subject] that estimate to a target rate of return” to “calculate a model guarantee fee.”

That’s nice, but here are the two questions that must be answered:

What is the cost of capital for a private regulated financial institution to bear the same credit risk as Fannie and Freddie?

What is the g-fee calculation based on that cost of capital for private institutions?

The FHFA has not answered these questions. Instead, the agency said it had “found no compelling economic reason to change the overall level of fees.” How about complying with the law?

Giant ‘QE’ gamble: How will it end?

Published in the Library Of Law And Liberty.

The Federal Reserve made a colossal gamble with its so-called “Quantitative Easing” or “QE,” which is simply a euphemism for its $4.4 trillion binge of buying long-term bonds and mortgages. Its big bid for long bonds, along with parallel programs undertaken by other members of the international fraternity of central banks, has artificially suppressed long-term interest rates, and has deliberately fostered asset-price inflations in bonds, stocks and houses.

Will this gamble pan out?

The Fed now intends to reduce its buying and slowly shrink its portfolio by letting bond maturities and mortgage prepayments exceed new purchases. As its big bid is reduced, will the asset-price inflations it fostered end well in some kind of soft landing, or will they end badly in an asset-price deflation? Will the Fed be able to take its stake off the table and go away a winner—or will it ultimately lose?

Nobody knows, including the Fed itself. The officials who run the institution are guessing, like everybody else—and hoping.

In particular, they are hoping that by making the unwinding of the gamble very slow, with emphatic announcements well in advance, they will mitigate the potential negative price reactions in bond, stock and housing markets. Well, maybe this strategy will work—or maybe not. The behavior of complex financial systems is fundamentally uncertain. As Nobel laurate economist Robert Shiller said in a recent interview with Barron’s, “We don’t know what will happen in this unwinding.”

Shiller is right. But who are the “we” who don’t know? In addition to himself, “we” includes Nobel laureates, all other economists, financial market actors, regulators, the Federal Reserve, all the other central banks, and you, honored reader and me.

With its buying in the trillions, the Fed made asset prices go up and long-term interest rates go down, as intended. Simply reversing its manipulation by selling in the trillions, turning its big bid in the market into a big offer, would surely make asset prices go down and interest rates go up, perhaps by a lot. This outcome the Fed wants at all costs to avoid. So it is not selling any of its bonds or mortgages. The plan is to stop buying as much, a little at a time, while continuing the steady stream of rhetorical assurances. We don’t know, and Fed officials don’t know, if this will work as hoped.

The Fed did not strive to inflate asset prices as an end in itself, of course. The theory was that this would result in a “wealth effect,” which would in turn accelerate economic growth. Did it? Would economic growth have been worse or better without QE? Were the risks entailed in the inflation of asset prices worth whatever additional growth it may or may not have induced? In fact, U.S. real gross domestic product growth over the many years of QE has been generally unimpressive.

“Evaluating the effects of monetary policy is difficult,” as Stephen D. Williamson, an economist with the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, writes in a new article in The Regional Economist, and “with unconventional monetary policy, the difficulty is magnified.” Williamson adds that “With respect to QE, there are good reasons to be skeptical that it works as advertised, and some economists have made a good case the QE is actually detrimental.” He points out that Canada without QE had better growth than the United States with it. As usual in macroeconomics, you can’t prove it one way or the other.

The Fed’s effect on asset prices seems clear, however. As one senior investment manager recently said about the price of the U.S. Treasury 10-year note, “What it tells you is the amount of distortion that quantitative easing is creating.” How much of that distortion is going to reverse itself?

With QE, the Fed has been practicing “asset transformation,” according to Williamson. That is economics-speak for borrowing short and lending long. The Fed is funding its long-term bonds and very long-term mortgage securities with short-term, floating-rate deposits. This is one of the most classic of all financial speculative gambles. In other words, the Fed has created a balance sheet for itself that looks just like a 1980s savings and loan, and has become, in effect, the biggest savings and loan in history.

Williamson reasonably asks if the Fed has any competitive advantage at holding such a speculative position, and doubts that it does. However, I believe the Fed does have two unique advantages in this respect: control of its own accounting, and lack of penalties for insolvency. The Fed uniquely sets its own accounting standards for itself, and Fed officials have decided never to mark its securities portfolio to market. More remarkably, even if it should realize losses on the actual sale of securities, officials have decided not to let such losses reduce its reported capital, but to carry the required debits to a hokey intangible asset account. No one else would be allowed to get away with that.

Suppose hypothetically that realized losses on the Fed’s giant portfolio come to exceed its small capital (less than 1 percent of the portfolio). Even then, it is not clear whether that would affect the Fed. Many economists argue that insolvency doesn’t matter if you can print the money to pay your obligations. Nonetheless, it would be embarrassing to the Fed to be technically insolvent, and its QE-unwind program is designed to avoid any realized losses while not disclosing any mark-to-market losses.

Although the GDP growth effects of the QE gamble are uncertain, it certainly has succeeded in two other ways besides inducing asset-price inflation: in robbing savers, and in allocating credit. By forcing real interest rates on conservative savings to be negative, the Fed has transferred billions of dollars of wealth from savers to borrowers—especially to the government, the biggest borrower of all, and to leveraged speculators. It has meanwhile assured the aggrieved savers that they are really better off being sacrificed for the greater good.

QE also means the Fed allocated trillions in credit to its favored sectors: housing and the government. In housing, this resulted in national average house prices inflating back up to their bubble levels, obviously making them less affordable. For the government, the Fed made financing its deficits cheaper and easier, and demonstrated once again that the real first mandate of any central bank is financing, as needed, the government of which it is a part.

As the Fed moves to unwind its big QE gamble, what will happen? It, and we, will find out by experience.

Taxpayers shouldn’t be asked to pay for Fannie and Freddie’s risk exposure

Published in The Hill.

As the old Washington saying goes, “When all is said and done, more is said than done.” This certainly applies to the years of congressional debates about how to reform Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. They are dominant forces in the huge American mortgage market, operating effectively as arms of the U.S. Treasury.

Can you ever protect the taxpayers against the risk of Fannie and Freddie? In their current form, with virtually zero capital — and soon literally zero capital — they are and will continue to be utterly dependent on the taxpayers’ credit card for their entire existence. Every penny of their income depends on the credit support of the taxpayers.

Since 2008, Fannie and Freddie have been a $5 trillion risk turkey, roosting in the dome of the Capitol. The members of Congress are unhappy and greatly irritated by its presence, but didn’t know how to get rid of this embarrassment their predecessors created.

Of course, even before their humiliating government conservatorship, Fannie and Freddie traded every minute on the credit of the U.S. Treasury and were always were a risk to the taxpayers. Although in those days they had some positive capital of their own, it was not very much capital relative to their risks. Without their free use of the taxpayers’ credit card, they would have been much smaller, much less leveraged, much less profitable and much less risky.

Once the Congress had set up Fannie and Freddie as government-sponsored risk takers, was there any way to remove the taxpayers’ risk exposure? The historical record offers little hope. No matter what any Treasury secretary or any other politician says, or even what any legislation provides, the global debt markets will simply not believe that two institutions representing half of all U.S. mortgage credit and sponsored by the U.S. government will not be bailed out by the Treasury. And the debt markets will be right.

In 1992, while revising the legislation that governs Fannie and Freddie, Congress solemnly tried to wiggle out of the problem. It added to the statutes of the United States a provision entitled, “Protection of Taxpayers Against Liability” for Fannie and Freddie’s debts. This “protection” is still on the books, although it did not provide any protection to the taxpayers.

Title XIII, “Government-Sponsored Enterprises,” of the Housing and Community Development Act of 1992, Section 1304, pronounced:

This title may not be construed as obligating the Federal Government, either directly or indirectly, to provide any funds to the Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation [Freddie], the Federal National Mortgage Association [Fannie], or the Federal Home Loan Banks, or to honor, reimburse or otherwise guarantee any obligation…

But naturally, when push came to shove in the housing-finance crisis, the federal government, directly and indirectly, did fully honor, entirely reimburse and effectively guarantee all the obligations of Fannie and Freddie anyway.

The statute went on to say:

This title may not be construed as implying that any such enterprise or bank, or any obligations or securities of such enterprise or bank, are backed by the full faith and credit of the United States.

Nice try, but no cigar. All the bond markets in the world knew that this fine language notwithstanding, all Fannie and Freddie’s obligations were in fact backed by the credit of the United States, as they still are and will continue to be.

What do you suppose the members of Congress who wrote and voted for those provisions were really thinking? Did they foolishly imagine that Fannie and Freddie could never actually get in financial trouble? Were they simply cynical, knowing that their provisions would not in fact protect the taxpayers? Or did at least some members of Congress truly believe they were doing something meaningful? One wonders.

The “protection of taxpayers” included in the 1992 act obviously failed. Can Congress avoid taxpayer risk from Fannie and Freddie next time? It seems unlikely in the extreme. But you might take a number of steps to reduce the inevitable taxpayer risk, including much higher capital requirements for Fannie and Freddie than heretofore, and charging a meaningful fee for the use of the taxpayers’ credit card, which will cause them to use it less.

There is one additional key lesson: government-sponsored enterprises, if they are created, should never, never be given perpetual charters like those given to Fannie and Freddie. If they were instead given limited life charters, say for 20 years (like First and Second Banks of the United States), Congress could at least periodically consider whether it would like to end the taxpayer risk game by not renewing the charter.

Treasury should not bail out Fannie and Freddie’s subordinated debt

Published in Economics 21.

When the U.S. Treasury bailed out Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac in 2008, holders of $13.5 billion in Fannie’s and Freddie’s subordinated debt—debt paid off after senior debt is repaid—were completely protected. Instead of experiencing losses to which subordinated lenders can be exposed when the borrower fails, they got every penny of scheduled payments on time.

The structural reasons for the unusual occurrence should be carefully examined by the Treasury to avoid its repetition.

This outcome was the exact opposite of the academic theories that had for years pushed subordinated debt as the way to create market discipline for financial firms that benefit from government guarantees on their senior obligations. In the event, Fannie’s and Freddie’s subordinated debt produced, and its holders experienced, zero market discipline. So much for the academic theories, at least as applied to government-sponsored enterprises.

“Perhaps surprisingly,” a Federal Reserve 2015 post-mortem study of the bailout says, “the two firms maintained their payments on the relatively small amount of subordinated debt they had.”

In terms of the theory that subordinated debt will be fully at risk, this is very surprising. As economist Douglas Elmendorf, former director of the Congressional Budget Office, wrote in criticism of this bailout detail, “The crucial role of subordinated debt for any company is to create a group of investors who know they will lose if the company fails.” But the Fannie and Freddie bailout was structured so that it didn’t happen.

The $13.5 billion is certainly a material number. While small relative to Fannie’s and Freddie’s immense liabilities, it was a significant part of their overall capital structure. In June 2008, Fannie and Freddie combined reported common equity of $18.3 billion and preferred stock of $35.8 billion, giving them, with the subordinated debt, total capital of $67.6 billion. The subordinated debt was thus 20 percent of reported total capital at that point, but it did not carry out its function as capital.

“In fact, subordinated debt is part of regulatory capital since the Basel I Accord (1988) and was always meant to absorb losses,” says a 2016 study for the European Parliament. Fannie and Freddie were not subject to the Basel Accord, but this nicely states the general theory.

“Market discipline is best provided by subordinated creditors,” wrote banking expert Paul Horvitz in 1983. A Federal Reserve study group produced the report “Using subordinated debt as an instrument of market discipline” in 1999. In 2000, Fed economists considered “a number of regulatory reform proposals aimed at capturing the benefits of subordinated debt” and concluded that it would indeed provide market discipline. “Ways to enhance market discipline… focused in large part on subordinated debt,” as a study by Fannie and Freddie’s regulator observed. Consistent with these theories, in October 2000, Fannie and Freddie committed to begin issuing publicly traded subordinated debt, and did. But bailout practice turned out to be inconsistent with the theory.

The Treasury knew precisely what it was doing for the subordinated debt holders. “These agreements support market stability,” said then-Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson’s Sept. 7, 2008 statement about the bailout, “by providing additional security and clarity to GSE debt holders—senior and subordinated—and support mortgage availability by providing additional confidence to investors…etc.” Treasury slipped that “and subordinated” in there in the middle of the paragraph, without any further comment or explanation.

“Under the terms of the agreement,” Paulson continued, “common and preferred shareholders bear losses ahead of the new government senior preferred shares.” But the government’s new senior preferred shares would by definition bear losses ahead of the subordinated debt. Why have the taxpayers be junior to the subordinated debt?

It appears that the Treasury was trapped as an unintended result of the Fannie and Freddie reform legislation of earlier in that bailout year, the Housing and Economic Recovery Act of 2008. A major battle in the creation of that act was to include the potential for receivership for Fannie and Freddie in the event of their failure—so, in theory, the creditors would have to consider the possibility of loss. Overachieving, Congress in HERA Section 1145 made receivership not just possible, but mandatory, in the event that Fannie and Freddie’s liabilities exceeded their assets and the regulator confessed it.

But in the midst of the financial crisis, the last thing Treasury wanted was a receivership, because the last thing they it wanted was to panic the creditors around the world by the prospect that they would be taking losses on Fannie’s and Freddie’s trillions of dollars of senior debt and MBS. Instead, they wanted to convince these creditors that there would be no losses. Treasury theoretically could have arranged to guarantee all the senior debt and MBS formally, but that would have forced the U.S. government to admit on its official books that it had an additional $5 trillion of debt. That would have been honest bookkeeping, but was an obvious nonstarter politically.

Once having decided against receivership, Treasury had to put the taxpayers’ money in as equity. Officials calculated that if Fannie and Freddie’s net worth were zero, their liabilities would not exceed their assets, so kept putting in enough new equity to bring the equity capital to zero. But once they had done that, there was no way to give the subordinated debt a haircut.

“We have been directed by FHFA to continue paying principal and interest on our outstanding subordinated debt,” Fannie reported. The covenants of the subordinated debt provided that if it were not being paid currently, no dividends could be paid by Fannie and Freddie—that would have included dividends on the Treasury’s senior preferred stock.

One reform idea, the mandatory receivership, had knocked out the previous reform idea that subordinated debt must take losses, and neither happened.

So financial theory notwithstanding, Fannie and Freddie’s subordinated debt achieved nothing. Its holders got a premium yield but were fully protected by the U.S. Treasury. The purchasers had made a very good bet on the financial behavior of governments when confronted with the failings of government-sponsored enterprises.

The 10th year since the bailout of Fannie and Freddie, and of their subordinated debt, will begin in September. Will Treasury now begin to address the structural issues?

Fannie and Freddie face the moment of truth on their taxpayer bailouts

Published in The Hill.

Almost nine years ago, in September 2008, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac were broke and put into government conservatorship by the Federal Housing Finance Agency. Less than two months before, the regulator had pronounced them “adequately capitalized.” As everybody knows, the U.S. Treasury arranged to bail them out with a ton of taxpayer money, ultimately totaling $187.5 billion, in order to get their net worth up to zero.

The original form of the bailout was senior preferred stock with a 10 percent dividend. By agreement between two parts of the government, the FHFA as conservator and the Treasury, the dividend was changed starting in 2013 from the original 10 percent to essentially 100 percent of the net profit of the two companies, whatever that turned out to be, in this notorious “profit sweep.”

By now, under the revised formula, Fannie and Freddie have paid in dividends to the Treasury $276 billion in total. That sounds like a lot more than $187.5 billion, a point endlessly repeated by the speculators in Fannie and Freddie’s still-existing common and junior preferred stock. Does this mean that Fannie and Freddie have economically, if not legally, paid off the Treasury’s investment? Nope. Not yet. But almost.

Let us suppose—which I believe to be the case—that the original 10 percent is a reasonable rate of return on the preferred stock for the taxpayers, who in addition got warrants for 79.9 percent of Fannie and Freddie’s common stock with an exercise price that rounds to zero. The 10 percent compares to the interest rate of 2 percent or so on 10-year Treasury notes and is greater than the average return on equity of 8 percent to 9 percent for banks in recent years.

The question is: When would all the payments by Fannie and Freddie to the Treasury constitute first a 10 percent annual yield on the preferred stock and then have been sufficient to retire all its par value with the cash that was left over?

This is easy to calculate. We lay out all the cash flows, all the investment that went into Fannie and Freddie from the Treasury, and all the dividends they paid to the Treasury, and calculate the cash-on-cash internal rate of return. When the internal rate of return gets to 10 percent, the economic payoff will have been achieved. I call this the “10 percent moment.”

As of the second quarter of 2017, the internal rate of return is 9.68 percent, so the 10 percent moment is close. If Fannie and Freddie pay the third quarter dividends they have projected, on a combined basis, the 10 percent moment will arrive in the third quarter of this year. The internal rate of return will have reached 10.02 percent.

However, viewing Fannie and Freddie separately, it is slightly more complex. Fannie is at 9.36 percent and should get to 10 percent by the fourth quarter of this year. Freddie has already made it, with an internal rate of return of 10.11 percent as of the second quarter of 2017.

At the 10 percent moment, let’s say the end of 2017, the Treasury could very reasonably and fairly consider its senior preferred stock as fully retired and agree to amend the agreements accordingly. Treasury should then also exercise all its warrants, to assure its 79.9 percent ownership of any future retained earnings and of whatever value the common stock may develop, guaranteeing the taxpayers the equity upside which was part of the original deal, and also assuring its voting control.

At that point, should it develop, the capital of Fannie and Freddie would still be zero. In this woefully undercapitalized state, they would still be regulated accordingly, and still be utterly dependent on the Treasury. They should begin immediately to pay a fee to the Treasury for its effective guaranty of their obligations. This fee should be charged on their total liabilities and be equivalent to what the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. would charge a large bank with their level of capital for deposit insurance — for starters, a bank with zero capital.

There are a few other requirements for this new deal for Fannie and Freddie. They should immediately be designated as the large and “systemically important financial institutions” they so obviously are by the Financial Stability Oversight Board. The massive systemic risk they represent should be supervised by the Federal Reserve, and their minimum capital requirement should be set at a 5 percent leverage capital ratio.

They must immediately start complying with the law that sets their guarantee fees at the level which a private financial institution would have to charge to cover its cost of capital. This requirement for guarantee fees is clearly established in the Temporary Payroll Tax Cut Continuation Act of 2011. Finally, they should pay the relevant state and local corporate income taxes, like everybody else.

Under these conditions, with the profit sweep and the senior preferred stock gone, but also with most of their economic rents and special government favors removed, Fannie and Freddie would have a reasonable chance to see if they could become successful competitors. They would still be too big to fail, of course, but they would be paying a fair price for the privilege.

The Fed: Can the world’s biggest S&L get back to normal?

Published in the Library Of Law And Liberty

The balance sheet of today’s Federal Reserve makes it the largest 1980s-model savings and loan in the world, with a giant portfolio of long-term, fixed-rate mortgage securities combined with floating-rate deposits. This would certainly have astonished the legislative fathers of the Federal Reserve Act, like congressman and later Sen. Carter Glass, who strongly held that the Fed should primarily be about discounting short-term commercial notes.

It would equally have amazed the Fed’s past leaders, like its longest-serving chairman, William McChesney Martin, who presided over the Fed under five U.S. Presidents, from 1951 to 1969. Martin thought the Fed should confine its open-market activities to short-term Treasury bills and instituted the “bills only doctrine” in 1953. He would have been most surprised and we can imagine displeased at the amount of Treasury bills now included in the Fed’s bloated $4.5 trillion of assets. As of June 7, 2017, the Treasury bills held by the Fed are exactly zero. This is as radical on one end of the maturity spectrum as the long-term mortgages are on the other.

As part of its so-called “quantitative easing” program—a more respectable-sounding name for buying lots of bonds—the Fed reports its mortgage securities portfolio as $1.77 trillion as of June 7. Its investment is actually somewhat larger than that, since the Fed separately reports $152 billion of unamortized premiums net of discounts it has paid. If we guess half of those premiums are attributable to the MBS, the total becomes $1.85 trillion. The Fed owns 18 percent of all the first mortgages in the country, which total $10 trillion. It owns nearly 30 percent of all the Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac and Ginnie Mae MBS that are outstanding. It is big, a market-moving position, and that was indeed the idea: to move the market for MBS up, mortgage interest rates down and house prices up.

The Fed has in its portfolio $2.46 trillion of long-term Treasury notes and bonds. Adding in the other half of the unamortized premiums brings its investment to $2.54 trillion. The Fed owns 24 percent of all the Treasury notes and bonds that are in the hands of the public. Again, a remarkably large, market-moving position.

The Fed’s problem is now simple and obvious: once you have gotten into positions so big relative to the market and moved the market up, how do you get out without sending the market down? The Fed is expending a lot of rhetorical energy on this problem.

As Federal Reserve chairman half a century ago, Martin was rightly skeptical of the advice of academic economists, but the control of the Fed is now dominated by academic economists. The former gold standard, whose last vestige disappeared when the United States reneged on its Bretton Woods commitments in 1971, has been replaced by what James Grant aptly calls “the Ph.D. standard.”

The Ph.D. standard is accompanied by the strident insistence that the Fed must be entirely and unconstitutionally independent, so that it can carry out whatever monetary experiments the debatable theories of its committee of economists lead to. Since 2008, nine years ago, these theories have concluded that the Fed should create “wealth effects,” which means manipulating upward the prices of houses, bonds and equities by buying a lot of long-term securities. In promoting asset-price inflation, the Fed, in company with the other major central banks, has greatly succeeded. Is that good?

It is one thing to try this in the midst of a crisis and a deep recession. But the last recession ended in mid-2009, eight years ago. The stock market has been rising for eight years, since the first quarter of 2009, passed its 2007 high in 2013 and has been dramatically booming since. House prices bottomed in 2012, have been rising much faster than incomes for five years and are, amazingly, back over their 2006 bubble peak.

So why is the Fed still buying long-term mortgages and bonds? It is definitely still a big bid in both markets, because it is continuing to buy in order to replace all the maturities and prepayments in its huge portfolio. Why doesn’t it just stop buying, instead of endlessly talking about the possibility of stopping, eight years after the end of crisis? Well, the Fed’s leaders want to manage your expectations, so you won’t think it’s a big deal–they hope–when it finally does really stop buying.

That time has still not come, the Fed just announced June 14. Perhaps later this year, although even this timing was hedged, it expects to allow a slight bit of runoff—but not now! The Fed would then still be buying, but a little less. This “very gradual and predictable plan” would start with reducing securities purchases by $10 billion a month. Annualizing that rate, in a year, the portfolio would go from $4.4 trillion to $4.3 trillion.

The Fed will continue its status as the world’s biggest S&L.

The major central banks form a tight fraternity. They have all been engaged in long-term securities-buying programs, the ultimate effects of which are subject to high uncertainty. Predictable human behavior, when subject to high uncertainty, is to herd together, to have the comfort of having the colleagues you respect all doing the same thing you are doing. This includes all thinking the same way and making the same arguments, that is, cognitive herding. Central banks are clearly not exempt from this basic human trait.

To paraphrase a famous line of John Maynard Keynes, “a prudent banker is one who goes broke when everybody else goes broke.” A central banking variation might be, “a prudent central banker is one who makes mistakes when everybody else is making the same mistakes.” Will this turn out to be the case with the matching “quantitative easing” purchases they did together?

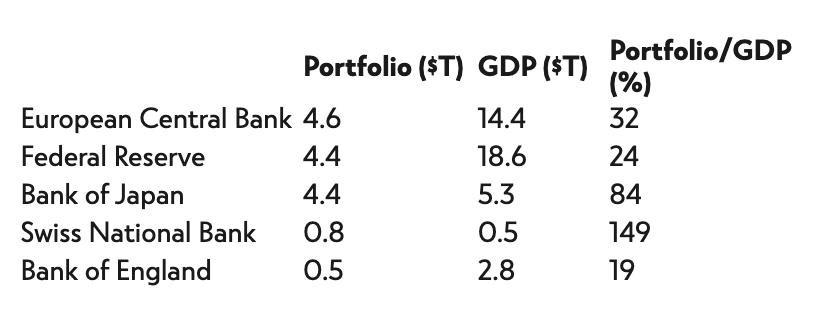

Here are the long-term securities portfolios of the elite of the central bank fraternity:

The European Central Bank has a slightly bigger bond portfolio than even the Fed does, but one significantly larger relative to the size of the economy. All these “quantitative easing” programs are definitely huge relative to the respective GDPs, the champion being the Swiss central bank with the remarkable size of 149 percent of gross domestic product. For better or worse, they are all in it together.

As a result of this massive central bank intervention, it is reasonably argued that there are no real market prices for bonds now—only central bank-manipulated prices. “Yields are too low in the U.S.,” as Abby Joseph Cohen of Goldman Sachs recently told Barron’s, and “there is no major economy with yields where they should be.”

What would happen to the Fed’s savings and loan-style balance sheet if interest rates did go back to normal? We know what happened to the savings and loan industry when interest rates went sharply up: they became insolvent. Could that happen to the Federal Reserve? Indeed. Let’s do the simple bond math.

What is the average duration of all the Fed’s long-term mortgages and bonds? A reasonable guess might be five years–if anything, this guess is easy on the Fed, and the duration of its mortgages will extend if rates rise. But let’s say five years. That means if long-term interest rates would rise by only 1 percent–not much—the market value of the Fed’s portfolio will fall by 1 percent x 5 = 5 percent. A 5 percent market loss on $4.4 trillion is $220 billion. Let’s compare that to the Federal Reserve System’s total capital, which is $40.8 billion. The Fed’s loss of market value on a 1 percent rise in long-term interest rates would be more than five times its capital.

Of course, interest rates might go up by more. A 2 percent rise would mean a market value loss of $440 billion, or more than 10 times the Fed’s capital. No wonder the Fed adamantly refuses to mark its securities portfolio to market!

Most economists confidently assert that no one would care at all if a fiat currency issuing central bank like the Fed became deeply insolvent on a mark-to-market basis. They may well be right. But in that case, why hide the reality of the market values?

The Swiss National Bank is required by its governing law to mark its securities portfolio to market and reflect that in its published financial statements. Why does the Federal Reserve lag behind the Swiss in disclosure and financial transparency?

Glass-Steagall never saved our financial system, so why revive it?

Published in The Hill.

The Banking Act of 1933 was passed in an environment of crisis. In March of that year, all of the nation’s financial institutions were closed in the so-called “bank holiday,” which followed widespread bank runs over the prior months.

Sen. Carter Glass, D-Va., a chief author of the bill and senior member of the Committee on Banking and Currency, was determined not to “let a good crisis go to waste.” Though he did not like the proposals from Chairman Henry Steagall, D-Ala., for federal deposit insurance, he agreed to support it on the condition that the legislation include Glass’ own pet idea that commercial banking be separated from much of the securities business.

It was poor policy from the start, but it took more than six decades to get rid of it. Now some political voices want to revive it. Financial ideas — like financial markets — have a cycle. Reviving Glass-Steagall would be an action with substantial costs, but no benefits. Its primary appeal seems to be as a political slogan.

Not having Glass-Steagall had nothing to do with the housing bubble or the resulting financial crisis of 2007 to 2009, except that being able to sell failing investment banks to big commercial banks was a major advantage for the regulators. And not having the law, in fact, had nothing to do with the crises of Glass’ own time, including the banking panic of 1932 to 1933 and the Great Depression.

Meanwhile, having Glass-Steagall in force did not prevent the huge, multiple financial busts of 1982 to 1992, which caused more than 2,800 U.S. financial institution failures, or the series of international financial crises of the 1990s.

While Glass-Steagall was in place, it required commercial banks to act, under Federal Reserve direction, as “the Fed’s assistant lenders of last resort,” whenever the Fed wanted to support floundering securities firms. This happened in the 1970 collapse of the commercial paper market, which followed the bankruptcy of the giant Penn Central Railroad, and in the “Black Monday” collapse of the stock market in 1987.

The fundamental problem of banking is always, in the memorable phrase of great banking theorist Walter Bagehot, “smallness of capital.” Or, to put the same concept in other words, the problem is “bigness of leverage.” So-called “traditional” commercial banking is, in fact, a very risky business, because making loans on a highly leveraged basis is very risky, especially real estate loans. All of financial history is witness to this.

Moreover, making investments in securities — that is, buying securities, as opposed to being in the securities business — has always been a part of traditional commercial banking. Indeed, it needs to be, for a highly leveraged balance sheet with all loans and no securities would be extremely risky and entirely unacceptable to any prudent banker or regulator.

You can make bad loans and you can buy bad investments, as many subprime mortgage-backed securities turned out to be. As a traditional commercial bank, you could make bad investments in the preferred stock of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, which created large losses for numerous banks and sank some of them.

Our neighbors to the north in Canada have a banking system that is generally viewed as one of the most stable, if not the most stable, in the world. The Canadian banking system certainly has a far better historical record than does that of the United States.

There is no Glass-Steagall in Canada: all the large Canadian banks combine commercial banking and investment banking, as well as other financial businesses, and the Canadian banking system has done very well. Canada thus represents a great counterexample for Glass-Steagall enthusiasts to ponder.

In Canada, there is now a serious question of a housing bubble. If this does give the Canadian banks problems, it will be entirely because of their “traditional” banking business of making mortgage loans — the vast majority of mortgages in Canada are kept on banks’ own balance sheets. If the bubble bursts, they will be glad of the diversification provided by their investment banking operations.

To really make banks safer, far more pertinent than reinstating Glass-Steagall, would be to limit real estate lending. Real estate credit flowing into real estate speculation is the biggest cause of most banking disasters and financial crises. Those longing to bring back their grandfather’s Glass-Steagall should contemplate instead the original National Banking Act, which prohibited real estate loans altogether for “traditional” banking.