Tags

Financial Systemic Issues: Booms and Busts - Central Banking and Money - Corporate Governance - Cryptocurrencies - Government and Bureaucracy - Inflation - Long-term Economics - Risk and Uncertainty - Retirement Finance

Financial Markets: Banking - Banking Politics - Housing Finance - Municipal Finance - Sovereign Debt - Student Loans

Categories

Blogs - Books - Op-eds - Letters to the editor - Policy papers and research - Testimony to Congress - Podcasts - Event videos - Media quotes - Poetry

The Oversight Board Keeps Working On Puerto Rico’s Record Insolvency

Published in Real Clear Markets.

The government of Puerto Rico continues to hold the all-time record for a municipal insolvency, having gone broke with over $120 billion in total debt, six times as much as the second-place holder, the City of Detroit.

Faced with this huge, complex, and highly politicized financial mess, and with normal Chapter 9 municipal bankruptcy legally not available, the Congress wisely enacted a special law to govern the reorganization of Puerto Rico’s debts. “PROMESA,” or the Puerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability Act, provided for a formal process supervised by the federal courts, in effect a bankruptcy proceeding. It also created an Oversight Board (formally, the Financial Oversight and Management Board for Puerto Rico) to coordinate, propose and develop debt settlements and financial reform. These two legislative actions were correct and essential. However, the Oversight Board was given less power than had been given to other such organizations. The relevant models are notably the financial control boards of Washington DC and New York City and the Emergency Manager of Detroit, all successfully called in to address historic municipal insolvencies and deep financial management problems.

It was clear from the outset that the work of the Puerto Rico Oversight Board was bound to be highly contentious, full of complicated negotiations, long debates about who should suffer how much loss, political and personal attacks on the Board and its members, and heated, politicized rhetoric. And so it proved to be. Since the members of the Oversight Board are uncompensated, carrying out this demanding responsibility requires of them a lot of public spirit.

An inevitable complaint about all such organizations, and for the Puerto Rico Oversight Board once again, is that they are undemocratic. Well, of course they are, of necessity, for a time. The democratically elected politicians who borrowed beyond their government’s means, spent the money, broke their promises, and steered the financial ship of state on the rocks should not remain in financial control. After the required period of straightening out the mess and re-launching a financial ship that will float, normal democracy returns.

It is now almost five years since PROMESA became law in June, 2016. It has been, as it was clear it would be, a difficult slog, but substantial progress has been made. On February 23, the Oversight Board announced a tentative agreement to settle Puerto Rico’s general obligation bonds, in principle the highest ranking unsecured debt, for on average 73 cents on the dollar. This is interestingly close to the 74 cents on the dollar which Detroit’s general obligation bonds paid in its bankruptcy settlement. If unpaid interest on these bonds is taken into account, this settlement results in an average of 63 cents on the dollar. In addition, the bondholders would get a “contingent value” claim, dependent on Puerto Rico’s future economic success—this can be considered equivalent to bondholders getting equity in a corporate reorganization–very logical.

The Oversight Board has just filed (March 8) its formal plan of adjustment. It is thought that an overall debt reorganization plan might be approved by the end of this year and that the government of Puerto Rico could emerge from its bankrupt state. Let us hope this happens. If it does, or whenever it ultimately does, Puerto Rico will owe a debt of gratitude to the Oversight Board.

We can draw two key lessons. First, the Oversight Board was a really good and a necessary idea. Second, it should have been made stronger, on the model of previous successes. In particular, and for all future such occasions, the legislation should have provided for an Office of the Chief Financial Officer independent of the debtor government, as was the case with the Washington DC reform. This was highly controversial, but effective. Any such board needs the numbers on a thorough and precise basis. Puerto Rico still is unable to get its audited annual reports done on time.

A very large and unresolved element of the insolvency of the Puerto Rican government remains subject to a debate which is important to the entire municipal bond market. This is whether the final debt adjustments should include some reduction in the almost completely unfunded government pension plans. Puerto Rico has government pension plans with about $50 billion in debt and a mere $1 billion or so in assets.

There is a natural conflict between bondholders and unfunded pension claims in all municipal finance, since not funding pensions is a back door deficit financing scheme. General obligation bonds are theoretically the highest ranking unsecured credit claims, and senior to unfunded pensions. But the reality is different. De facto, reflecting powerful political forces, pensions are the senior claim. Pensions did take a haircut in the Detroit bankruptcy, but a significantly smaller one than did the most senior bonds. In other municipal bankruptcies, unfunded pensions have come through intact.

What should happen in Puerto Rico? The Oversight Board has recommended modest reductions in larger pensions, reflecting the utter insolvency of the pension plans. Puerto Rican politicians have opposed any adjustment at all. Bondholders of Illinois: take note of this debate.

I suggest a final lesson: the triple-tax exemption of interest on Puerto Rican bonds importantly contributed to its ability to run up excess and unpayable debts. Maybe there was a rationale for this exemption a hundred years ago. Now Puerto Rico’s bonds should be put on the same tax basis as all other municipal bonds.

Unfunded Pensions: Watch out, bondholders!

Published in Real Clear Markets.

A reorganization plan for the debt of the government of Puerto Rico was submitted to the court Sept. 27 by the Puerto Rico Oversight Board. It covers $35 billion of general obligation and other bonds, which it would reduce to $12 billion.

On average, that is about a 66 percent haircut for the creditors, who thus get 34 cents on the dollar, compared to par. Pretty steep losses for the bondholders, but steep losses were inevitable given the over-borrowing of the Puerto Rican government and the previous over-optimism of the lenders. Proposed haircuts vary by class of bonds, but run up to 87 percent, or a payment of 13 cents on the dollar, for the hapless bondholders of the Puerto Rican Employee Retirement System.

In addition to its defaulted bonds, the Puerto Rican government has about $50 billion in unfunded pension obligations, which are equivalent to unsecured debt. But the pensioners do much better than the bondholders. Larger pensions are subject to a maximum reduction of 8.5 percent, while 74 percent of current and future retirees will have no reduction. Those with a reduction have the chance, if the Puerto Rican government does better than its plan over any of the next 15 years, to have the cuts restored.

The Oversight Board’s statement does not make apparent what the overall haircut to pensions is, but it is obviously far less than for the bondholders. “The result is that retirees get a better deal than almost any other creditor group,” as The New York Times accurately put it. This may be considered good and equitable, or unfair and political, depending on who you are, but it is certainly notable. The Times adds: “Legal challenges await the plan from bondholders who believe the board was far too generous to Puerto Rico’s retired government workers.”

The Puerto Rican debt reorganization plan demonstrates once again, in municipal insolvencies and bankruptcies, unfunded pension obligations are de facto a senior claim compared to any other unsecured debt, including general obligation bonds that pledge the full resources and taxing power of the issuing government. This is not because they are legally senior, but because they are politically senior.

By running up their unfunded pensions, municipalities have not only stressed their own finances, but have effectively subordinated the bondholders. When it comes to unfunded pensions, the Puerto Rico outcome, like that of Detroit and others, announces: Bondholders, Watch Out!

Fund managers are the agents of shareholders

Published in the Financial Times.

“Large institutional shareholders, notably BlackRock, State Street and Vanguard, recognise that companies must serve broader social purposes,” writes Martin Lipton (Opinion, September 18). There is one big problem with this statement: these firms are not shareholders. They are mere agents for the real shareholders whose money is at risk. They are moreover agents that display all the conflicts of classic agency theory. Yet they go about calling themselves “shareholders”, pushing the personal political agendas of their executives.

What they should be doing is finding out what the real shareholders desire and voting shares accordingly as faithful agents, not pontificating about personal ideas, which are irrelevant as far as what shareholders want.

Is the Fourth of July really the Second?

Published by the R Street Institute.

We all know about Fourth of July picnics, parades and fireworks. We all know the celebration is about the Declaration of Independence and the birth of our country. But how much else do we know about the beginning of American independence? Here is a little quiz to help celebrate the Fourth with some history.

On what date was the decision made to declare American independence?

The answer is not July 4, but July 2, 1776. This was when the truly decisive event occurred, the vote of the Second Continental Congress that America should separate itself from England. The vote was preceded by days of debate about a motion of June 7.

That these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States, that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown.

On July 2 this motion was adopted, with 12 colonies in favor, none against and one abstention (New York, which later added its affirmative vote).

July 2 “marked the great decision from which there was no turning back,” as one historian wrote.

What happened July 4?

On July 4, Congress approved the final, revised text of the full document of the Declaration, which not only declared independence but gave philosophical and historical reasons for it. The Declaration was signed that day by President of the Congress John Hancock and Secretary of the Congress Charles Thomson. None of the other signatures were added until Aug. 2 or later.

The printer worked all that night to make copies for distribution. The published text bears the famous date of July 4 and began to be sent around America July 5.

What about July 3?

July 3 marked a painful experience for Thomas Jefferson, the Declaration’s principal drafter. Having already made the great decision, the Congress sat down to edit, criticize and revise the draft which Jefferson had prepared. Anybody who has had a paper amended by a committee can especially sympathize with Jefferson each July 3.

What is most of the Declaration about?

Much of the Declaration, about 55 percent of its text, is devoted to listing all the faults and misdeeds of King George III. This list is about three times as long as the most famous passage setting forth the truths held to be self-evident.

The Declaration has four basic parts:

An introduction (“When in the course of human events”)

A philosophical justification (“We hold these truths to be self-evident”)

The list of King George’s misdeeds

The concluding resolutions of independence, of which the heart is the original motion quoted above.

The third, longest part concludes that King George is “a prince whose character is marked by every act which may define a tyrant.”

Does the Declaration discuss a new country?

This question is a little tricky, because it depends on the idea of “a” or one new country. The Declaration always refers to the 13 colonies in the plural. It says, “These United Colonies are Free and Independent States.”

The new states that set out to be free and independent immediately began working on how they would form a confederation or a union. This question was not settled until the implementation of the Constitution in 1789—or it might be argued, not until the conclusion of the Civil War in 1865.

Did the Declaration begin the Revolutionary War?

No, the Declaration grew out of a war already begun more than a year before. The fighting at Lexington and Concord, Massachusetts, occurred April 19, 1775, or more than 14 months before the decision to declare independence.

When did America achieve independence?

It is one thing to announce plans and another to carry them out. The Revolutionary War dragged on for years after the Declaration, with great difficulties and despair, as well as vision and courage. These years also included high inflation, caused by the Continental Congress printing paper money to finance the army.

Independence was finally achieved when Great Britain acknowledged it by the Treaty of Paris in 1783, seven years after the Declaration.

How long has it been since you read the Declaration of Independence?

It is an excellent read, for its world-historical importance, dramatic setting, intellectual substance and eloquent language.

Cuestionan definición de servicios esenciales

Published in Metro PR.

Amanda Rivera, directora ejecutiva del Instituto del Desarrollo de la Juventud de Puerto Rico; Ana Cristina Gómez, profesora de la Escuela de Derecho de la Universidad de Puerto Rico (UPR), y Alex Pollock, del R Street Institute, también presentaron sus ponencias ante el comité cameral.

Demócratas y republicanos parecen ir por caminos distintos sobre la ley Promesa

Published in El Nuevo Dia.

El experto en finanzas Alex Pollock, del grupo R Street y quien fue invitado a la audiencia por la minoría republicana, recomendó que la JSF tenga más poderes y pidió al Congreso nombrar un jefe de finanzas que también funcione por encima del gobierno electo de Puerto Rico.

Como varios congresistas republicanos, Pollock criticó que el gobierno de Puerto Rico no haya publicado los informes financieros auditados de 2016, 2017 y 2018.

U.S House Natural Resources Committee Holds Hearing on Puerto Rico

Published in The Weekly Journal.

The U.S. House Committee on Natural Resources holds a hearing today on the status of Puerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability Act (PROMESA): Lessons Learned Three Years Later.

Natural Resources committee Chairman Raúl Grijalva presides the 10 a.m. oversight hearing at the Longworth House Office Building.

Gov. Ricardo Rosselló, Natalie A. Jaresko, Executive Director, Financial Oversight and Management Board for Puerto Rico; Martín Guzmán, Non-Resident Senior Fellow for Fiscal Policy, Espacios Abiertos; Amanda Rivera, Executive Director, The Institute for Youth Development of Puerto Rico; Ana Cristina Gómez-Pérez, Associate Professor, University of Puerto Rico; and Alex J. Pollock, Distinguished Senior Fellow, R Street Institute are part of the witness list.

Testimony to the House Committee on Natural Resources at Hearing on “The Status of the Puerto Rico Oversight, Management and Economic Stability Act (PROMESA): Lessons Learned Three Years Later”

Published by the R Street Institute.

Six Lessons

Mr. Chairman, Ranking Member Bishop, and Members of the Committee, thank you for the opportunity to be here today. I am Alex Pollock, a senior fellow at the R Street Institute, and these are my personal views. I have spent almost five decades working in and on the banking and financial system, including studying the recurring insolvencies of municipal and sovereign governments. I have personally experienced and studied numerous financial crises and their political aftermaths, and have authored many articles, presentations, testimony and two books on related subjects. Prior to R Street, I was a resident fellow at the American Enterprise Institute 2004-2016, and President and CEO of the Federal Home Loan Bank of Chicago 1991-2004.

In my view, there are six key lessons about PROMESA, the massive insolvency of the government of Puerto Rico, and the role of the Oversight Board we should consider. These are:

The fundamental bargain of PROMESA was sound. But it could be improved.

In such situations, a lot of conflict and controversy is unavoidable and certain.

The Oversight Board should have more power: in particular, it should have the same Chief Financial Officer provisions as were so successfully used in the Washington DC reforms.

Oversight boards are likely to last more than three years. In Puerto Rico, all the problems were of course made more difficult by the destructive hurricanes, and the flow of federal emergency funds into the Puerto Rican economy now makes the financial problems more complex.

Large unfunded pensions are a central element in these situations and set up an inescapable conflict between the claims of bondholders and pensioners.

Progress must operate on three levels of increasing difficulty:

Equitable reorganization of the debt (including pension debt)

Reform for efficiency and reliability in the fiscal and financial functioning of the government

Reforms which allow a growing, enterprising successful market economy to emerge from the historic government-centric economy.

The fundamental bargain of PROMESA was sound. But it could be improved.

As it considered PROMESA, the Congress was faced with a municipal insolvency of unprecedented size. As one analyst correctly wrote, “There is no municipal borrower remotely as insolvent as Puerto Rico.” Indeed, adding together its $70 billion in bond debt and $50 or $60 billion in unfunded pension debt, the government of Puerto Rico has debt of more than six times that of the City of Detroit, the previous all-time record holder, as it entered bankruptcy.

The fundamental bargain Congress constructed in PROMESA to cope with Puerto Rico’s financial crisis made and makes good sense. It may be described as follows:

-To the Puerto Rican government: We will provide reduction and restructuring of your unpayable debts, but only if it is accompanied by fundamental financial and government reform.

-To the creditors: You will get an appointed board to oversee and reform Puerto Rico’s finances, but only if it also has debt reduction powers.

This is a sound bargain. The resulting Oversight Board created by the act was and is, in my judgment, absolutely necessary. But its members, serving without pay, were as we all know, given an extremely difficult responsibility. So far, significant progress has been made, but much remains to do. Let us hope the Senate promptly confirms the existing members of the Board, so that its work may continue uninterrupted.

In the negotiations leading to PROMESA, it was decided to create an Oversight Board, less powerful than a control board. I thought at the time, and it seems clear in retrospect, that it would have been better—and would still be better–for it to have more of the powers of a financial control board, as discussed further under Lesson 3.

Two well-known cases of very large municipal insolvencies in which financial control boards were successfully used were those of New York City and Washington DC. In 1975, New York City was unable to pay its bills or keep its books straight, having relied on, as one history says, “deceptive accounting, borrowing excessively, and refusing to plan.” In 1995, Washington was similarly unable to pay its vendors or provide basic services, being mired in deficits, debt and financial incompetence.

Today, New York City has S&P/Moody’s bonds ratings of AA/Aa1, and Washington DC of AA+/Aaa. We should hope for similar success with the financial recovery of Puerto Rico.

In such situations, a lot of conflict and controversy is unavoidable and certain.

Nothing is less surprising than that the actions and decisions of the Oversight Board have created controversy and criticism, or that “the board has spent years at odds with unhappy creditors in the mainland and elected officials on the island.”

As one Oversight Board member, David Skeel, has written, the Board “had been sharply criticized by nearly everyone. Many Puerto Ricans and economists…argued that our economic projections were far too optimistic…. Creditors…insisted that the economic assumptions in the fiscal plan were unduly pessimistic and…provided too little money for repayment.”

The settlement of defaults, reorganization of debt and creation of fiscal discipline is of necessity passing out losses and pain, accompanied by intense negotiations. Of course, everyone would like someone else to bear more of the loss and themselves less. It is utterly natural in the “equitable reorganization of debt” for insolvent debtors and the creditors holding defaulted debt to have differing views of what is “equitable.”

If only one side were critical of the Oversight Board, it would not be doing its job. If it is operating as it should, both sides will complain, as will both ends of the political spectrum. In this, I believe we must judge the Oversight Board successful.

The financial control boards of New York City and Washington DC are now rightly considered as a matter of history to have been very successful and to have made essential contributions to the recovery of their cities. But both generated plenty of complaints, controversy, protests and criticism in their time.

In Washington, for example, “city workers protested by blocking the Control Board’s office with garbage trucks during the morning rush hour.” In the board’s first meeting, “protesters shouted ‘Free D.C.’ throughout the meeting, which was brought to an end by a bomb threat.” Later, “in one of its most controversial actions, the Board fired the public school superintendent, revoked most of the school board’s powers, and appointed its own superintendent to lead the system.”

In New York, the board “made numerous painful, controversial decisions that the administration of Mayor Abraham D. Beame was unwilling or unable to make. It ordered hundreds of millions of dollars in budget cuts above those proposed by the administration and demanded the layoffs of thousands of additional city workers. It rejected a contract negotiated by the city’s Board of Education…it also rejected a transit workers’ contract.”

What did this look like at the time? “In the eyes of many people in the city, it was most distasteful,” said Hugh Carey, then Governor of New York State. “They saw the control board as the end of home rule, as the end of self-government.” Another view: “The city of New York was like an indentured servant.”

In restructurings of debt and fiscal operations, it has been well observed that a “key factor is making sure that the sacrifice is distributed fairly.” But what is fair is necessarily subject to judgment and inevitably subject to dispute.

The Oversight Board should have more power: in particular it should have the same Chief Financial Officer provisions as were so successfully used in the Washington DC financial reforms.

As PROMESA came into effect, as has been observed, “The most obvious obstacle…was that no one really knew what Puerto Rico’s revenues and expenditures were.” This financial control mess, stressed by expert consultants at the time, highlights the central role in both creating and fixing the debt crisis, of financial management, reporting and controls. Progress had been made here with efforts of both the Oversight Board and Puerto Rico, as the certified fiscal plan has been developed. But the government of Puerto Rico still has not completed its audited financial statements for 2016 or 2017, let alone 2018.

Of the historical instances of financial control boards in municipal insolvencies, there is a key parallel between Puerto Rico and Washington DC: in both cases, there is no intervening state. The key role played by New York State, or by Michigan in the Detroit bankruptcy, for example, is missing. The reform and restructuring relationship is directly between the U.S. Congress and the local government.

The most striking difference between the Washington DC board and the Oversight Board is the greater power of the former. This was true in the initial design in 1995, but when Congress revised the structure in 1997 legislation, the Washington board was made even stronger. Most notably, the Washington design included the statutory Office of the Chief Financial Officer, which answered primarily to the control board and was independent of the mayor. Puerto Rico has created its own Chief Financial Officer, as good idea as far as it goes, but it lacks the reporting relationship to the Oversight Board and the independence which were fundamental to the Washington reforms.

Today, long after Washington’s financial recovery, the independence remains. As explained by the current Office of the Chief Financial Officer (OCFO) itself:

“In 1995, President Clinton signed the law creating a presidentially appointed District of Columbia Financial Control Board…. The same legislation…also created the position of Chief Financial Officer, which had direct control over day-to-day financial operations of each District agency and independence from the Mayor’s office. In this regard, the CFO is nominated by the Mayor and approved by the DC Council, after which the nomination is transmitted to the U.S. Congress for a thirty-day review period.

“The 2005 District of Columbia Omnibus Authorization Act…reasserted the independence and authority of the OCFO after the Control Board had become a dormant administrative agency on September 30, 2001, following four consecutive years of balanced budgets and clean audits.”

If PROMESA were ever to be revised, for example trading additional financial support for additional reform and financial controls, as happened in the Washington DC case in 1997, I believe the revision should include structuring an Office of the Chief Financial Officer for Puerto Rico on the Washington DC model.

Oversight boards are likely to last more than three years. In Puerto Rico, all the problems were of course made more difficult by the hurricanes, and the flow of emergency funds into the Puerto Rican economy now makes the financial problems more complex.

As we come up on the third anniversaries of PROMESA and the Oversight Board, we can reflect on how long it may take to complete the Oversight Board’s responsibilities of debt reorganization and financial and fiscal reform. More than three years.

The New York City control board functioned from 1975 to 1986, or eleven years. There was a milestone in 1982, which was the resumption of bank purchases of its municipal bonds. That took seven years.

The Washington DC control board operated from 1995 to 2001, or six years. (Both boards still remain in the wings, capable of resuming activity, should the respective cities backslide in their financial disciplines.)

Everything in the Puerto Rico financial crisis was made more uncertain and difficult by the destruction from the disastrous hurricanes of 2017. Now, as in response, large amounts of federal disaster aid are flowing into the Puerto Rican economy.

How much this aid should be is of course a hotly debated political issue. But whatever it turns out to be, this external flow makes the formation of the long-term fiscal plan more complex. Whether the total disaster relief is the $82 billion was estimated by the Oversight Board, the $41 billion calculated as so far approved, or some other number, it is economically a large intermediate-term stimulus relative to the Puerto Rican economy, with its GDP of approximately $100 billion.

There are significant issues of how effectively and efficiently such sums will be spent, what the economic boost will be as they generate spending, employment and government revenues, whether they can result in sustainable growth or only a temporary effect, and therefore how they will affect the long-term solvency and debt-repayment capacity of the government of Puerto Rico. Even if none of these funds go to direct debt payment, their secondary effects on government revenues may. How to think through all this is not clear (at least to me), but a conservative approach to making long-term commitments based on short-term emergency flows does seem advisable.

The Oversight Board will have to come up with some defined approach to both long and short-term outlooks, as it continues its double project of debt reorganization and fiscal reform. That is yet another difficult assignment for them, requiring time and generating controversy.

Large unfunded pensions are a central element in these situations and set up an inescapable conflict between the claims of bondholders and pensioners.

Puerto Rican government pension plans are not only underfunded, they are basically unfunded. At the time a PROMESA, a generally used estimate of the pension debt was $50 billion, which added to the $70 billion in bond debt made $120 billion in all. It appears that there is in addition $10 billion in unfunded liabilities of government corporations and municipalities, making the pension debt $60 billion, and thus the total debt, before reorganization haircuts, $130 billion. As I learned from an old banker long ago, in bankruptcy, assets shrink and liabilities expand.

How are the competing claims of bondholders and pensioners equitably to be settled? This is an ever-growing issue in municipal and state finances—very notably in Illinois and Chicago, for example, as well as plainly in Puerto Rico. The bankruptcy settlement of the City of Detroit did give haircuts to pensions—a very important precedent, in which the state constitution of Michigan was trumped by federal bankruptcy law. But the pensions turned out in Detroit, as elsewhere, to be de facto senior to all unsecured bond debt. This reflects the political force of the pensioners’ claims and needs.

On April 30, the Oversight Board demanded that the government of Puerto Rico act to enforce required contributions to pension funds from several public entities and municipalities. It is “unacceptable to withhold retirement contributions from an employee and not immediately transfer that money into the individual retirement account where it belongs,” wrote our colleague on the panel, Natalie Jaresco. She is right, of course. Except that it is worse than “unacceptable”—it is theft.

Pensions as a huge component of municipal insolvencies will continue to be a tough issue for the Oversight Board, as well as for a lot of other people.

Progress must operate on three levels of increasing difficulty:

Equitable reorganization of the debt (including pension debt)

Reform for efficiency and reliability in the fiscal and financial functioning of the government

Reforms which allow a growing, enterprising successful market economy to emerge from the historic government-centric economy.

Three years into the process, the first of these requirements is difficult and controversial, but well under way.

The second is harder, because it is challenging government structures, embedded practices, power, and local politics. Relative to addressing insolvency, the most important areas for reform are of course the financial and fiscal functions. Reform would be advanced by the creation of an Office of the Chief Financial Officer on the Washington DC model.

The third problem is by far the most difficult. Solving the first two will help make solving the third possible, but the question of how to do this is not yet answered, subject to competing theories, and major uncertainty. We all must hope for the people of Puerto Rico that it will nonetheless happen.

Thank you again for the chance to share these views.

Let’s get rid of Puerto Rico’s triple-tax exemption

Published by the R Street Institute.

Let’s ask a simple and necessary question: Why in the world is the interest on Puerto Rican bonds triple-tax exempt all over the United States, when no U.S. state or municipality gets such favored treatment?

The municipal bond market got used to that disparity, but in fact, it makes no sense. It is an obvious market distortion, on top of being unfair to all the other municipal borrowers. It helped lure investors and savers, and mutual funds as intermediaries, into supporting years of overexpansion of Puerto Rican government debt, ultimately with disastrous results. It is yet another example of a failed government notion to push credit in some politically favored direction. Investors profited from their special exemption from state and local income taxes on interest paid by Puerto Rico; now, in exchange, they will have massive losses on their principal. Just how big the losses will be is still uncertain, but they are certainly big.

Where did that triple-tax exemption come from? In fact, from the Congress in 1917. The triple-tax exemption is celebrating its 100th anniversary this year by the entry of the government of Puerto Rico into effective bankruptcy. Said the 1917 Jones-Shafroth Act:

All bonds issued by the government of Porto Rico or of by its authority, shall be exempt from taxation by the Government of the United States, or by the government of Porto Rico or of any political or municipal subdivision thereof, or by any State, or by any county, municipality, or other municipal subdivision of any State or Territory of the United States, or by the District of Columbia.

That’s clear enough. But why? Said U.S. Sen. James K. Vardaman, D-Miss., at the time: “Those people are underdeveloped, and it is for the purpose of enabling them to develop their country to make the securities attractive by extending that exemption.” All right, but 100 years of a special favor to encourage development is enough, especially when the result was instead to encourage massive overborrowing and insolvency.

It’s time to end Puerto Rico’s triple-tax exemption for any newly issued bonds (as there will be again someday). As we observe the unhappy 100th birthday of this financial distortion, it’s time to give it a definitive farewell.

Puerto Rico: Storms and savings

Published by the R Street Institute.

Puerto Rico has a long history of many disastrous hurricanes, as once again this year with the devastating Hurricane Maria. These disasters recur frequently, historically speaking, in an island located “in the heart of hurricane territory.” Some notable examples follow, along with descriptions excerpted from various accounts of them.

In 1867, “Hurricane San Narciso devastated the island.” (Before reaching Puerto Rico, it caused “600 deaths by drowning and 50 ships sunk” in St. Thomas.)

In 1899, Hurricane San Ciriaco “leveled the island” and killed 3,369 people, including 1,294 drowned.

In 1928, “Hurricane San Felipe…devastated the island”…“the loss caused by the San Filipe hurricane was incredible. Hundreds of thousands of homes were destroyed. Towns near the eye of the storm were leveled,” with “catastrophic destruction all around Puerto Rico.”

In 1932, Hurricane San Ciprian “caused the death of hundreds of people”…“damage was extensive all across the island” and “many of the deaths were caused by the collapse of buildings or flying debris.”

In 1970, Tropical Depression Fifteen dumped an amazing 41.7 inches of rain on Puerto Rico, setting the record for the wettest tropical cyclone in its history.

In 1989, Hurricane Hugo caused “terrible damage. Banana and coffee crops were obliterated and tens of thousands of homes were destroyed.”

In 1998 came Hurricane Georges, “its path across the entirety of the island and its torrential rainfall made it one of the worst natural disasters in Puerto Rico’s history”…“Three-quarters of the island lost potable water”…“Nearly the entire electric grid failed”…“28,005 houses were completely destroyed.”

In 2004, Hurricane Jeanne caused “severe flooding along many rivers,” “produced mudslides and landslides,” “fallen trees, landslides and debris closed 302 roads” and “left most of the island without power or water.”

And in 2017, as we know, there was Hurricane Maria (closely following Hurricane Irma), with huge destruction in its wake.

These are some of the worst cases. On this list, there are nine over 150 years. That is, on average, one every 17 years or so.

All in all, if we look at the 150-year record from 1867 to now, Puerto Rico has experienced 42 officially defined “major hurricanes”—those of Category 3 or worse. Category 3 means “devastating damage will occur.” Category 4 means “catastrophic damage will occur.” And Category 5’s catastrophic damage further entails “A high percentage of framed homes will be destroyed…Power outages will last for weeks to possibly months. Most of the area will be uninhabitable for weeks or months.”

Of the 42 major hurricanes since 1867 in Puerto Rico, 16 were Category 3, 17 were Category 4 and 9 were Category 5, according to the official Atlantic hurricane database.

Doing the arithmetic (150 years divided by 42), we see that there is on average a major hurricane on Puerto Rico about every 3.5 years.

There is a Category 4 or 5 hurricane every 5.8 years, on average.

And Category 5 hurricanes occur on average about every 17 years.

There are multiple challenging dimensions to these dismaying frequencies–humanitarian, political, engineering, financial. To conclude with the financial question:

How can the repetitive rebuilding of such frequent destruction be financed? Thinking about it in the most abstract way, somewhere savings have to be built up. This may be either by self-insurance or by the accumulation of sufficiently large premiums paid for insurance bought from somebody else. Self-insurance can include the cost of superior, storm-resistant construction. Or funds could be borrowed for reconstruction, but have to be quite rapidly amortized before the next hurricane arrives. Or somebody else’s savings have to be taken in size to subsidize the recoveries from the recurring disasters.

Is it possible for Puerto Rico to have a long-term strategy for financing the recurring costs of predictably being in the way of frequent hurricanes, other than using somebody else’s savings?

Virgin Islands follow Puerto Rico into the debt day of reckoning

Published by the R Street Institute.

What do Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands have in common? They are both islands in the Caribbean, they are both territories of the United States and they are both broke.

Moreover, they both benefited (or so it seemed in the past) from a credit subsidy unwisely granted by the U.S. Congress: having their municipal bonds be triple-tax exempt everywhere in the country, something U.S. states and their component municipalities never get. This tax subsidy helped induce investors and savers imprudently to overlend to both territorial governments, to finance their ongoing annual deficits and thus to create the present and future financial pain of both.

Puerto Rico, said a Forbes article from earlier this year—as could be equally said of the Virgin Islands—“could still be merrily chugging along if investors hadn’t lost confidence and finally stopped lending.” Well, of course: as long as the lenders foolishly keep making you new loans to pay the interest and the principal of the old ones, the day of reckoning does not yet arrive.

In other words, both of these insolvent territories experienced the Financial Law of Lending. This, as an old banker explained to me in the international lending crisis of the 1980s, is that there is no crisis as long as the lenders are merrily lending. The crisis arrives when they stop lending, as they inevitably do when the insolvency becomes glaring. Then everybody says how dumb they are for not having stopped sooner.

Adjusted for population size, the Virgin Islands’ debt burden is of the same scale as that of Puerto Rico. The Virgin Islands, according to Moody’s, has public debt of $2 billion, plus unfunded government pension liabilities of $2.6 billion, for a total $4.6 billion. The corresponding numbers for Puerto Rico are $74 billion and $48 billion, respectively, for a total $122 billion.

The population of the Virgin Islands is 106,000, while Puerto Rico’s is 3.4 million, or 32 times bigger. So we multiply the Virgin Islands obligations by 32 to see how they compare. This gives us a population-adjusted comparison of $64 billion in public debt, and unfunded pensions of $83 billion, for a total $147 billion. They are in the same league of disastrous debt burden.

What comes next? The Virgin Islands will follow along Puerto Rico’s path of insolvency, financial crisis, ultimate reorganization of debt, required government budgetary reform and hoped for economic improvements.

A final similarity: The Virgin Islands’ economy, like that of Puerto Rico, is locked into a currency union with the United States from which, in my opinion, it should be allowed to escape. This would add external to the imperative internal adjustment, as the debt day of reckoning arrives.

Detroit and Puerto Rico: Which is the worse insolvency?

Published in Real Clear Markets.

Over four decades beginning in the 1970s, the U.S. financial system had one big municipal debt crisis per decade. These were New York City in the 1970s, the Washington Public Power Supply System (“Whoops!”) in the 1980s, Orange County, California in the 1990s, and Jefferson County, Alabama in the 2000s.

But our current decade, not yet over, has already set two consecutive all-time records for the largest municipal insolvencies in history: first the City of Detroit, which entered bankruptcy in 2013, and then Puerto Rico, which is now in an equivalent of bankruptcy especially created for it by Congress (under Title III of the PROMESA Act of 2016).

Between bonds, unfunded pensions, and other claims, Detroit’s record-setting debt upon bankruptcy was $18.8 billion. Puerto Rico has far surpassed that. Its comparable debt is $122 billion, or 6.5 times that of Detroit, with $74 billion in bonds and $48 billion in unfunded pensions.

On the other hand, Puerto Rico is five times bigger than Detroit, with a population of 3.4 million, compared to 687,000. We need to look at the problems on a per capita basis.

The result is not optimistic for the creditors of Puerto Rico. As shown below, Puerto Rico’s debt per capita is much bigger—33% higher– than Detroit’s was in 2013: about $35,800 versus $26,900.

Total debt Population Debt per capita

Puerto Rico $122 billion 3,411,000 $35,800

Detroit $ 18.8 billion 687,000 $27,400

On top of more debt, Puerto Rico has much less income per capita—23% less—than Detroit did. So as it arrives in court for a reorganization of its debts, its ratio of debt per capita to income per capita is 3.1 times, compared to 1.8 times for Detroit. As shown below, this is 70% greater relative debt—or alternately stated, Puerto Rico’s per capita income to debt ratio is only 59% of Detroit’s.

Puerto Rico Detroit PR/ Detroit Detroit/ PR

Total debt per capita $35,800 $27,400 131% 77%

Income per capita $11,400 $14,900 77% 131%

Per capita debt / income 3.14x 1.84x 170% 59%

Puerto Rico’s unemployment rate is very high at over 12%. This not as huge as Detroit’s 22%, but Puerto Rico’s abysmal labor participation rate of 40%, compared to Detroit’s already low 53%, offsets this difference. This leaves Puerto Rico with proportionally even fewer earners with lower incomes to pay the taxes to pay the much higher debt.

On a macro basis, then, it appears that the creditors of Puerto Rico can expect to do even more poorly than those of Detroit. How poorly was that?

At its exit from a year and a half of bankruptcy, Detroit’s total debt had been reduced to $10.1 billion. Overall, this was 53 cents on the dollar, or a loss of 47% from face value, on average. However, various classes of creditors came out very differently. Owners of revenue bonds on self-supporting essential services came out whole on their $6.4 billion in debt. If we exclude this $6.4 billion, leaving $12.4 billion in claims by everybody else, the others all together got $3.7 billion, or a recovery of 30 cents on the dollar, or a loss of 70%, on average.

Recoveries in this group ranged from 82 cents on the dollar for public employee pensions, to 74 cents for the most senior general obligation bonds, to 44 cents on more junior bonds, to 25 cents for settling swap liabilities, to 13 cents on certificates of participation, to 10 cents on non-pension post-retirement benefits and other liabilities. It is noteworthy that the public employee pensions did take a meaningful haircut, although they came out far better than most others. The pension settlement also included special funds contributed by the State of Michigan and special funds contributed by charitable foundations to protect the art collection of the Detroit Institute of Arts. These latter factors will not be present in the Puerto Rico settlement.

As a macro estimate, if we take as a baseline Detroit’s average settlement of 53 cents on the dollar and multiply it by Puerto Rico’s 59% of Detroit’s ratio of per capita income to debt, we get a guess of 31 cents on average for all the creditors. This is not extremely different from the official fiscal plan approved by the Puerto Rico Oversight Board, which estimates cash available for debt service of about 24% of the contractual debt service over the next ten years.

What will happen in the debt reorganization bargains, what role pension debt will play, how various classes of creditors will fare with respect to each other, what political actions there may be—all is up in the air as the court begins its work.

The lenders and borrowers responsible for the huge financial mistakes which led to deep insolvency need to seriously think through, as in every debt disaster, “How did we get ourselves into this mess?!” They are a long way from getting out of it.

Puerto Rico’s inevitable debt restructuring arrives

Published by the R Street Institute.

“Debt that cannot be repaid will not be repaid” is Pollock’s Law of Finance. It applies in spades to the debt of the government of Puerto Rico, which is dead broke.

Puerto Rico is the biggest municipal market insolvency and, now, court-supervised debt restructuring in history. Its bond debt, in a complex mix of multiple governmental issuers, totals $74 billion. On top of this, there are $48 billion in unfunded public-pension liabilities, for a grand total of $122 billion. This is more than six times the $18.5 billion with which the City of Detroit, the former municipal insolvency record holder, entered bankruptcy.

The Commonwealth of Puerto Rico will not enter technical bankruptcy under the general bankruptcy code, which does not apply to Puerto Rico. But today, sponsored by the congressionally created Financial Oversight and Management Board of Puerto Rico, it petitioned the federal court to enter a similar debtor protection and debt-settlement proceeding. This framework was especially designed by Congress for Puerto Rico under Title III of the Puerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability Act (PROMESA) of 2016. It was modeled largely on Chapter 9 municipal bankruptcy and will operate in similar fashion.

This moment was inevitable, and Congress was right to provide for it. It is a necessary part of the recovery of Puerto Rico from its hopeless financial situation, fiscal crisis and economic malaise. But it will make neither the creditors, nor the debtor government, nor the citizens of Puerto Rico happy, for all have now reached the hard part of an insolvency: sharing out the losses. Who gets which losses and how much the various interested parties lose is what the forthcoming proceeding is all about.

The proceedings will be contentious, as is natural when people are losing money or payments or public services, and the Oversight Board will get criticized from all sides. But it is responsibly carrying out its duty in a situation that is difficult, to say the least.

There are three major problems to resolve to end the Puerto Rican financial and economic crisis:

First, reorganization of the government of Puerto Rico’s massive debt: this began today and will take some time. In Detroit, the bankruptcy lasted about a year and a half.

Second, major reforms of the Puerto Rican government’s fiscal and financial management, systems and controls. Overseeing the development and implementation of these is a key responsibility of the Oversight Board.

Third—and by far the most difficult step and the most subject to uncertainty—is that Puerto Rico needs to move from a failed dependency economy to a successful market economy. Economic progress from internally generated enterprise, employment and growth is the necessary long-term requirement. Here there are a lot of historical and political obstacles to be overcome. Not least, as some of us think, is that Puerto Rico is trapped in the dollar zone so it cannot have external adjustment by devaluing its currency.

The first and second problems can be settled in a relatively short time; the big long-term challenge, needing the most thought, is the third problem.

The story of the Puerto Rican financial and economic crisis just entered a new chapter, but it is a long way from over.

Letter to Oversight Board of Puerto Rico

Published by the R Street Institute.

In response to your request for public comments on the draft Puerto Rico fiscal plan, I respectfully submit the following thoughts.

An old friend of mine who ran a publishing company was famous for returning manuscripts to hopeful authors with this note written at the top: “OK to revise.” This is my summary view of the draft plan for three reasons:

The recent elections in both Puerto Rico and the United States resulted in changing both administrations. Presumably a new governor and new members of the U.S. Treasury Department will have different or additional positions to explore.

The draft plan entirely sidestepped the critical question of how to approach the debt restructuring obviously required.

The draft plan likewise sidestepped the essential questions about how to address the insolvent public-pension plans of Puerto Rico.

However, parts of the draft plan should, in my opinion, enter into final form and implementation as rapidly as practicable. These are the programs to improve budget controls, financial reporting, rationalization of expenditures, effectiveness of tax collections and, in general, all programs to promote stronger financial management and financial integrity. It seem to me that these should be put into a separate plan document for individual and expedited consideration.

To these essential programs should, in my opinion, be added the creation of a chief financial officer for Puerto Rico, closely modeled on the very successful Office of the Chief Financial Officer of Washington, D.C., which was one of the key reforms under its Financial Control Board in the 1990s.

It would be a pleasure to provide any other information which might be useful.

Yours respectfully,

Alex J. Pollock

Economic reform for Puerto Rico

Published by the R Street Institute.

The attached letter was submitted to the Bipartisan Congressional Task Force on Economic Growth in Puerto Rico.

Among the most fundamental of Puerto Rico’s many economic problems is that it is “stuck in a monetary union with the United States” (as Desmond Lachman of the American Enterprise Institute has correctly characterized it). In this situation of being forced to use the U.S. dollar, the Puerto Rican economy is simply uncompetitive, but the use of exchange rate policies to improve competitiveness or cushion budget tightening’s impact on domestic demand is precluded.

This is the same massive problem that Greece had and still has from being stuck in the monetary union of the euro. With any external currency adjustment forbidden, all the adjustment falls on internal reduction of costs. As Greece demonstrates, this continues to be very difficult and daunting, both economically and politically. This is true even after its creditors have taken huge haircuts. Puerto Rico’s creditors will take big haircuts, too, but that won’t solve its ongoing lack of competitiveness or the impact of the required budget tightening.

The European Union leadership feared that Greece’s exit from the euro might set off the unraveling of their whole common currency project. In contrast, there is not the slightest possibility that whatever happens in Puerto Rico will affect the stability or dominant role of the U.S. dollar. Even in the Greek case, European policy makers did seriously consider a back-up plan for a paper currency to be issued by Greek banks which would certainly have depreciated against the euro.

Dr. Lachman argues that Puerto Rico “needs the boldest of economic programs.” My suggestion is that the Task Force should consider “thinking about the unthinkable,” and include in its work a study of the “outside the box” possibility of currency reform for Puerto Rico. This would involve creating a new Puerto Rican currency which would be considerably devalued with respect to the U.S. dollar, thus allowing external, not only wrenching internal, adjustment of Puerto Rico’s uncompetitive cost structures. There is plenty of precedent for such currency reform, although this case is certainly complicated by the status of Puerto Rico as a territory. Could a U.S. territory have its own currency? Why not?

In such a study, one would have to consider the balance sheets of all the Puerto Rican depositories and how they would be affected in detail by denomination in a new currency, how various contracts would be affected, how exchange between the new currency and other currencies would be introduced, whether a new Puerto Rican central bank would be established, and many other problems of transition and functioning, of course. Existing Puerto Rican government debt in U.S. dollars would not be subject to redenomination, but this debt, a growing amount of it in default, is going to have to be significantly written down in any case.

Does the current monetary union pose deep problems for Puerto Rico? Undoubtedly. Would it make sense to release Puerto Rico from being stuck in a monetary union in which it cannot compete? Possibly. Would this be better than the Greek model of forcing internal cost deflation while providing big external subsidies? Probably. It does seem sensible to take a serious look at the possibility of currency reform.

Thank you for the chance to comment on this critical issue. It would be a pleasure to provide any further information which might be helpful.

The Senate needs to pass the House’s Puerto Rico bill

Published by the R Street Institute.

The government of Puerto Rico is broke. It now has multiple defaults on its record, most recently for $367 million in May. More and bigger defaults are on the way, probably beginning July 1. It’s already June 22.

The U.S. Senate should pass the U.S. House’s Puerto Rico bill now.

The House approved the bill by a wide margin, after a long and thorough bipartisan discussions that included sensible compromises and ultimate agreement between the administration and the legislators. The bill gets all the essential points right. These are:

The creation of an emergency financial control board, or “Oversight Board,” to get under control and straighten out the financial management and fiscal balance of the Puerto Rican government.

An orderly and equitable process overseen by the board to address restructuring the government’s unpayable debts.

Beginning a long-term project to move Puerto Rico toward a successful market economy and away from its failed government-centric one.

Of course, any complex set of legislative provisions can give rise to arguments and possibly endless debates about details. That would be a big mistake.

It’s time to enact the bill and get the essentials in place as soon as possible.

R Street and Americans for Tax Reform urge the Senate to pass H.R. 5278 (PROMESA)

Published by the R Street Institute.

June 21, 2016

Dear Senator,

On behalf of the undersigned free market organizations, we urge you to vote “Yes” on the House-passed H.R. 5278, the Puerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability Act of 2016 (PROMESA). Puerto Rico faces many challenges, and unfortunately the territory’s fiscal challenges cannot be fixed overnight. However, by putting strong, independent oversight in place, requiring fiscal reforms, and creating a path for addressing financial debt, PROMESA lays the foundation for prudent fiscal management that will lead to future solvency.

The Puerto Rican crisis is the result of many years of fiscal and economic mismanagement, and both the island’s own government and the federal government are complicit. While untangling the web of failed policy will take time, the fact remains: Puerto Rico is broke. The Puerto Rican government is already failing to meet its debt obligations, and with every day that passes, the probability of a crisis increases.

With defaults, combined unfunded pension and debt obligations over $115 billion, and the Puerto Rican government’s failure to produce audited financial statements for several fiscal years, it is imperative to establish financial oversight, get an accurate understanding of the situation, and create an appropriately calibrated fiscal plan to restore growth. The Oversight Board set out in PROMESA is empowered to do exactly this. The Oversight Board will exercise its authority to acquire accurate financial information, establish fiscal plans, create budgets, negotiate with creditors, and ensure enforcement of the deals and plans created under its authority.

While this oversight control is the required first step toward abating Puerto Rico’s crisis, PROMESA also enacts several immediate pro-growth reforms, including altering the island’s unemployment generating minimum wage requirements and overtime regulations, and putting a plan in place for infrastructure improvements. These changes are an important part of altering the island’s path, and we urge the congressional task force created by the bill to search for further opportunities to reform policies currently limiting Puerto Rico’s growth and promote a market economy.

PROMESA lays out a process to ensure the island’s creditors are treated justly during any future debt restructuring. It encourages voluntary restructuring, requires the Oversight Board to ‘respect the relative lawful priorities’ of the various debt classes, and distinguishes between debt obligations and pensions.

We applaud the House for its leadership on this issue. The bill has been strengthened, and currently represents Puerto Rico’s best chance to return solid fiscal footing. It is now the Senate’s turn. By voting for passage, Senators will fulfill their obligation under the Constitution to ‘make all the needful rules’ regarding the territories. We urge you therefore to vote yes.

Sincerely,

R Street Institute

Americans for Tax Reform

Time for Congress to vote in the new Puerto Rico bill

Published by the R Street Institute.

A revised bill to address the intertwined debt, fiscal and economic crises of Puerto Rico has just been introduced in the U.S. House. H.R. 5278 proposes “to establish an Oversight Board, to assist the Government of Puerto Rico…in managing its public finances.”

This “assistance” (read, “supervision”) is needed intensely. If all goes well, the House Natural Resources Committee will report the bill out promptly and it will proceed to enactment.

As is well-known, the government of Puerto Rico is broke and defaulting on its debt. At $118 billion, by the committee’s reckoning (which rightly includes unfunded government pensions), that debt is six times the total debt and unfunded pensions of the City of Detroit as it entered bankruptcy. This is a truly big insolvency, which reflects long years of constant fiscal deficits filled in by excess borrowing. Moreover, as the committee points out, Puerto Rico’s “state-run economy is hopelessly inefficient.”

There are three fundamental tasks involved in the complex and massive problems, and the bill addresses all three. These are:

To establish an emergency financial control board to determine the extent of the insolvency, develop fiscal and operational reforms and put the government of Puerto Rico on a sound financial basis. The bill uses the more politic title of “Oversight Board,” but the tasks are the same. They will not be easy and are sure to be contentious, but are necessary.

To restructure the unpayable debt and settle how the inevitable losses to creditors are shared among the parties. The bill gives the Oversight Board the authority, if necessary, to put forth a plan of debt reorganization and the legal framework to reach settlement.

To move Puerto Rico toward economic success – that, is toward a market economy and away from its failed government-centric economy – and thus to give it the potential for future growth. These reforms will not be easy, either, but the bill sets out a process to start the required evolution.

The discussion of the necessary steps has been long and full. Now it’s time for Congress to vote in the new bill.

Puerto Rico: A big default—what next?

Published in the Library Of Law And Liberty.

Rexford Tugwell, sometimes known as “Rex the Red” for his admiration of the 1930s Soviet Union and his fervent belief in central planning, was made governor of Puerto Rico by President Franklin Roosevelt in 1941. Among the results of his theories was the Government Development Bank of Puerto Rico, a bank designed as “an arm of the state,” which is a central element in the complicated inner workings of the Puerto Rican government’s massive insolvency.

The bank has just defaulted on $367 million of bonds – the first, but unless there is congressional action, not the last, massive default by the Puerto Rican government and its agencies on their debt. The Government Development Bank was judged insolvent in an examination last year, but the finding was kept secret. The governor of Puerto Rico has declared a “moratorium” on the bank’s debt, which means a default. A broke New York City in 1975 also defaulted and called it a “moratorium.”

Adding together the Puerto Rican government’s explicit debt of about $71 billion and its unfunded pension liabilities of about $44 billion amounts to $115 billion. This is six times the $18 billion in bonds and pension debt of the City of Detroit, which holds the high honor of being the largest municipal bankruptcy ever.

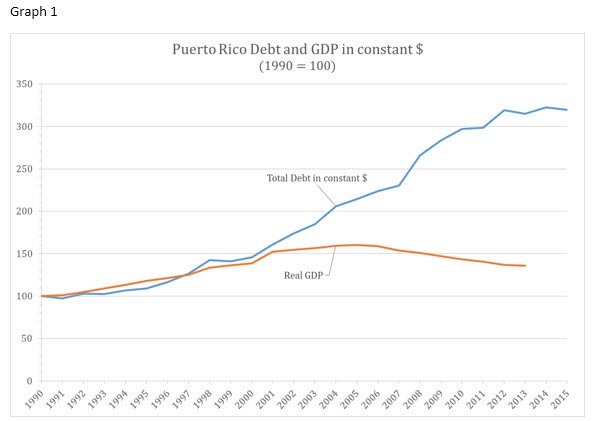

Puerto Rico’s government-centric political economy goes back to Rex the Red, but its budget problems are also long-standing. In this century, the government has run a deficit every year, borrowed to pay current expenses, and then borrowed more to service previous debt until the lenders belatedly ceased lending and the music stopped. Its debt and its real gross domestic product definitively parted company in 2001 and have grown continuously further apart, as shown Graph 1.

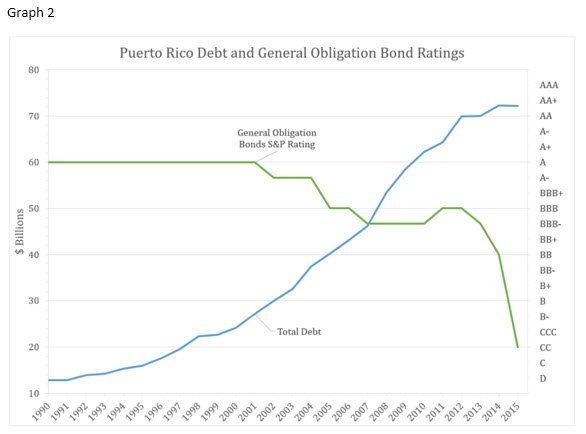

As its debt skyrocketed, the credit ratings of its bonds fell and then crashed. See Graph 2.

Where do we go from here? Addressing the deep, complicated, and contentious problems requires three steps:

The creation of an emergency financial control board to assume oversight and control of the financial operations of the government of Puerto Rico, which has displayed incompetence in fiscal management (or mismanagement), is a central aspect of the solution. This control board can be modeled on those successfully employed to address the insolvencies and financial mismanagement in the District of Columbia in the 1990s, in New York City in the 1970s and in numerous other places. More recently, the City of Detroit got an emergency manager along the same lines.

Such a board would be and must be quite powerful. The sine qua non for financial reform is to establish independent, credible authority over all books and records; to determine the true extent of the insolvency of the many indebted government entities—in particular to get on top of the real condition of the Government Development Bank; and to develop fiscal, accounting, control and structural reforms which will lead to future balanced budgets and control of the level of debt.

Needed reforms cited by Puerto Rican economist Sergio Marxuach in congressional testimony include:

[I]ncrease tax revenues by improving enforcement efforts, closing down ineffective tax loopholes, and modernizing its property tax system; crackdown on government corruption; significantly improve its Byzantine and unduly opaque financial reporting; reform an unnecessarily complicated permitting and licensing system that stifles innovation; … lower energy and other costs of doing business.

That’s a good list of projects.

Does all this take power and responsibility away from the Puerto Rican government? Of course it does – it needs to and it can be done. Under the Constitution, Congress has complete jurisdiction over territories like Puerto Rico. Just as in Washington and New York City, when the problems are straightened out, financial management will revert to the normal local government.

Pollock’s Law of Finance states that “Loans which cannot be repaid, will not be repaid.” Naturally, this law applies to the $115 billion owed by the Puerto Rican government, which is on its way to some form of restructuring and reorganization of debts. It seems clear that this should be done in a controlled, orderly and equitable process, which takes into account the various levels of seniority and standing among the many different classes of creditors.

The pending House bill puts the proposed oversight board in the middle of the analysis and negotiations of competing claims. If the reorganization cannot be voluntarily agreed upon, the process can move to the federal court, where the plan of reorganization would come from the oversight board.

Three objections have been made to this approach. One that has been advertised heavily claims that it is a “bailout.” Since no taxpayer money is planned to go to creditors, this is simply wrong and ridiculous. Bondholders taking losses is the opposite of a bailout.

A second is that bondholders may be disadvantaged versus pension claims, and this may affect the whole municipal bond market. Indeed, in the Detroit bankruptcy, the general obligation bonds got 74 cents on the dollar, while the general city employee pensions got 82 cents— an important haircut, but a smaller one. The political force of pension claims in insolvencies is a credit fact that all investors must take into account. If the national municipal bond market internalizes and prices the risks of unfunded pensions, thereby bringing more discipline on the borrowers, that seems like progress to me.

A third objection is that the bill’s approach would set a precedent for financially struggling states like Illinois, which they might follow. In my judgment, there is zero probability that Illinois or any other state would volunteer to have a financial control board imposed on it. Even leaving aside the fact that Puerto Rico is not a state, this argument is vacuous.

Of fundamental importance is that in the medium term, Puerto Rico must develop a sustainable economy—that is, a market economy to replace its historically government-centric one. Various ideas have been proposed relevant to this essential goal, and much more work is required. This is the most challenging of all the elements of the problem. Steps 1 and 2 must be done first, but Step 3 must be achieved for ongoing success.

One thoughtful investor in municipal bonds, reflecting on Puerto Rico, Illinois and other troubled political entities, concluded, “We don’t trust governments.” That made me think of how there have been more than 180 defaults and restructurings of sovereign debt in the last 100 years and how, further back, a number of American states defaulted on their debts and even repudiated them. So I wrote him, “I think that’s wise.”

Nonetheless, the immediate requirement to deal with the Puerto Rican debt crisis is government action.

Puerto Rico: Time for Congress to act

Published by the R Street Institute.

The finances of Puerto Rico’s government are unraveling rapidly. With the commonwealth government broke and scrambling, its Legislative Assembly already has empowered Gov. Alejandro García Padilla to declare a moratorium on all debt payments.

In a report that was kept secret, the Government Development Bank, which is at the center of complex intragovernmental finances, was found last year to be insolvent. Adding together the explicit government debt and the liabilities of its 95 percent unfunded government pension plan, the total problem adds up to about $115 billion.

There is no pleasant outcome possible here. The first alternative available is to deal with many hard decisions and many necessary reforms in a controlled fashion. The second is to have an uncontrolled crisis of cascading defaults in a territory of the United States.

Congress needs to choose the controlled outcome by creating a strong emergency financial control board for Puerto Rico—and to do it now. This is the oversight board provided for in the bill currently before the House Natural Resources Committee. The bill further defines a process to restructure the Puerto Rican government’s massive debts, which undoubtedly will be required.

Some opponents of the bill, in a blatant misrepresentation, have been calling it a “bailout” to generate popular opposition. To paraphrase Patrick Henry, these people may cry: Bailout! Bailout!…but there is no bailout.

Enacting this bill is the first step to get under control a vast financial mess, the result of many years of overborrowing, overlending and financial and fiscal mismanagement.

Again to cite Patrick Henry, “Why stand we here idle?”